Identifying the type of scoliosis Richard suffered from and how it may have affected him was a truly interesting discovery. When scientists at the University of Leicester failed to deliver on their repeated promises of many more marvellous historical discoveries, they instead attempted to focus on an allegedly controversial break in paternity, allowing the media to capitalize on it and create as many lurid headlines as they could manage. They had no new significant findings about Richard III himself. Kevin Shurer is now attempting to trace the lineage of celebrities back to Richard III. A triumph in genealogical research indeed.

Journalist Dan Jones then chimed in, claiming that those who object to disturbing the dead are “squeamish and prissy” and asking if it was time to “look inside that urn in Westminster Abbey containing the supposed remains of the princes in the Tower? Or to stick a camera inside Elizabeth I’s tomb?”1 Perhaps the Bisley Boy theory has him enchanted.

It’s inevitable that the subject of the remains alleged to be King Edward V’s and Richard Duke of York’s in the urn in Westminster Abbey would be broached. Queen Elizabeth II and the Church of England have repeatedly refused requests to examine the remains. And it is no wonder. There may be some fragments of animal bones left in the urn, who knows what the media will come up with?

An endlessly long line of historians have stated it is possible that the remains found in the Tower of London in 1674 belong to King Edward V and Richard Duke of York. It’s about time we let go of an idea that has no basis in fact.

The facts are that King Edward V’s and Richard Duke of York’s graves have never been discovered, and their remains do not lie in an urn in Westminster Abbey.

“At the stayre foote, metely depe in the grounde”

Thomas More’s brilliant discourse against tyranny, The History of Richard III, is at the root of this myth. More himself would probably be mystified that his dramatic interpretation of the alleged murder of Edward V and Richard Duke of York would be used as historical evidence a few centuries later. More’s historians will point out that he did have access to reliable oral sources, various men and women who had lived through Richard III’s reign. His historians also examine literary influences on his work such as Suetonius, Tacitus and Sallust, Seneca, Plautus and Euripides, and even the medieval mystery plays that More himself loved to write and act in as a young boy. More’s History of King Richard III is usually viewed as a moral anecdote, a rhetorical exercise. Peter Ackroyd has even suggested it “may have been the basis of exercises given to his own school or even to the boys of St Paul’s: there is a sudden reference to a ‘scole master of Poules” for no good reason.”2 Tyranny was a recurring theme in More’s work, and as Richard Sylvester points out “a subject for philosophical meditation as well as an ever-present danger in the kingdom.”3 On the other hand, some examining the mystery of ‘The Princes in the Tower’ will use selective phrases from More to validate the discovery of a pair of children’s skeletons found in the Tower of London in 1674.

There have actually been two sets of children’s skeletons discovered in the Tower of London that were thought to have belonged to Edward V and Richard Duke of York. There is an old story of a pair of skeletons found in a ‘walled-up room’ in the Tower of London in the early 1600s. A note, dated 17 August 1647, is written on the flyleaf of a 1641 manuscript of Thomas More’s History. Helen Maurer’s examination notes that this particular story was dismissed because the bones were in “the wrong places at the wrong times.”4 The first discovery may have been ignored because it did not fit with the more compelling account in More’s History, that the boys were buried “at the stair foot, metely deep in the ground under a great heap of stones.”

This sentence has captured the imagination of many, when one fails to note the next part of the account. More follows on to tell us that King Richard III,”allowed not, as I have heard, the burying in so vile a corner, saying that he would have them buried in a better place, because they were a king’s sons…Wherupon they say that a priest of Sir Robert Brakenbury took up the bodies again, and secretely entered them in such place, as by the occasion of his death, which he only knew it, could never since come to light.”

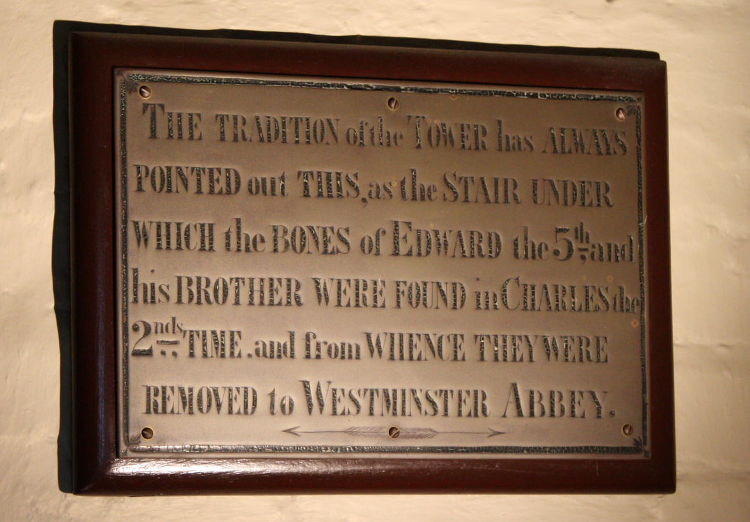

The 1674 discovery of a pair of children’s skeletons, found when workmen were demolishing the staircase leading to the White Tower in the Tower of London, has somehow given more weight to More’s account. Or perhaps the first part of More’s account gave more weight to it. A report of the discovery first appeared in Francis Sandford’s Genealogical History of the Kings of England published in 1677.

“Upon Friday the … day of July, An. 1674 …in order to the rebuilding of the several Offices in the Tower, and to clear the White Tower of all contiguous buildings, digging down the stairs which led from the King’s Lodgings, to the chapel in the said Tower, about ten foot in the ground were found the bones of two striplings in (as it seemed) a wooden chest, which upon the survey were found proportionable to ages of those two brothers viz. about thirteen and eleven years. The skull of one being entire, the other broken, as were indeed many of the other bones, also the chest, by the violence of the labourers, who….cast the rubbish and them away together, wherefore they were caused to sift the rubbish and by that means preserved all the bones. The circumstances of the story being considered and the same often discoursed with Sir Thomas Chichley, Master of the Ordinance, by whose industry the new buildings were then in carrying on, and by whom the matter was reported to the King: upon the presumptions that these were the Bones of the said Princes…”

The first problem with this discovery is the soil level. A level of ten feet indicates that the remains must have been much older than 200 years. There have been ancient remains found in the Tower before, and as late as 1977 the skeleton of a child found in the Tower was dated to the Iron Age. A hasty grave could not have been dug deeper than a foot or two. In 1674 it took a team of workmen to dismantle the staircase. The remains were found at foundation level, a depth that would have required scaffolding, and the digging itself would have taken days. The soil level could have risen no more than a couple of feet between 1483 and 1674.

Charles II did not have the remains reinterred immediately. In fact they languished until a warrant was issued in 1677 ordering an urn to made for ‘the supposed bodyes of ye two Princes’. The wording itself indicates that the remains were not thought to be that of Edward V and Richard Duke of York with absolute certainty. The sudden speed with which this belated interment was arranged saw chicken and fish bones and three rusty nails cobbled into the urn along with the remains of the two children, clearly debris from their sojourn on the rubbish heap. Maurer notes that, taking the uncertainty of Charles’s succession into account, the remains “made touching symbols of the evils of deposition and thwarted succession” and the sudden decision to inter the remains was a “political act, fraught with a political message for Charles’s own time.”5

Westminster Abbey’s translation of the Latin inscription reads:

Here lie the relics of Edward V, King of England, and Richard, Duke of York. These brothers being confined in the Tower of London, and there stifled with pillows, were privately and meanly buried, by the order of their perfidious uncle Richard the Usurper; whose bones, long enquired after and wished for, after 191 years in the rubbish of the stairs (those lately leading to the Chapel of the White Tower) were on the 17th day of July 1674, by undoubted proofs discovered, being buried deep in that place. Charles II, a most compassionate prince, pitying their severe fate, ordered these unhappy Princes to be laid amongst the monuments of their predecessors, 1678, in the 30th year of his reign.

An examination was conducted on the bones in 1933 by Lawrence Tanner, Keeper of the Muniments at Westminster Abbey, Professor William Wright, President of the Anatomical Society of Great Britain and Dr George Northcroft, president of the Dental Association. Among other things they concluded that they were the bones of two children, the eldest aged twelve to thirteen and the younger nine to eleven. Yet they failed to determine the sex of the skeletons, a fundamental piece of information.

The presence of two children’s skeletons in a vast area where various remains have been discovered before proves very little. We cannot use Thomas More’s account as historical evidence that Edward V and Richard Duke of York were murdered in the Tower of London and buried at the foot of the stairs in the White Tower, because the account is fictional. And even in this fictional account More himself did not come to this conclusion. More said they were taken from their hastily-dug grave at the foot of the stairs and reburied in a secret location, with the only man who knew their whereabouts then rather conveniently dying.

We can see that, even in 1677, these remains were not thought to be the remains of Edward V and Richard Duke of York beyond all reasonable doubt. We can see that the depth of the burial does not indicate the remains were almost 200 years old, but much older. It is evident that Charles II was probably sending a political message against deposition with his own succession in doubt. We know that the sex of the two skeletons was not determined in the examination in 1933. We have no definitive way of conducting any tests, the mtDNA John Ashdown-Hill discovered cannot be used to test these remains.

We have no archaeological evidence. We have no scientific proof. We have no historical record. So it cannot be said with any certainty whatsoever that the remains in Westminster Abbey belong to Edward V and Richard Duke of York. In fact it can be said with far more certainty that they do not.

Theyr bodies cast God wote where

Thomas More was a careful scholar. After his gripping account of the “most piteous and wicked…lamentable murder of his innocent nephews the young King and his tender brother” he also noted that “some remain yet in doubt, whether they were in [Richard’s] days destroyed or no“. More regularly indicates he was using second-hand information, as wise men think, men constantly say, as the story runs and even either men of hatred reported the above for truth or...Thomas More knew that no one could prove who murdered the sons of Edward IV, or if indeed they were murdered at all. If Thomas More knew men and women who had lived in Richard III’s reign and he could not find out the truth, what hope do we have 500 years later? Whomsoever knew the fate of Edward V and Richard Duke of York took the secret to the grave.

When the issue was raised again in 2012 the dean of Westminster replied “If the result is positive, the remains of the two princes are placed back in Sir Christopher Wren’s urn. But what if they are negative: what do we do with the remains?

“Keep them in the urn in the royal chapels, knowing they are bogus, or re-bury them elsewhere? And what would we have gained, other than to satisfy our curiosity in one area. It would not bring us any nearer the truth of the affair.”6

Many seem to be under the impression that if DNA testing proved the remains in Westminster Abbey did not belong to Edward V and Richard Duke of York that it would exonerate Richard III of the crime. It would do nothing of the sort. It would be far more likely that the blame was placed firmly back at the hands of Richard III. Every time the demands to test the remains are raised it gives more credence to the ridiculous myth that a set of random, unidentified pair of skeletons found in the Tower of London could possibly belong to Edward V and Richard Duke of York. And if it was proven the skeletons did not belong to them, it would simply prove what we should have known all along.

It would be the greatest irony that some would claim a negative result simply proved that Thomas More was correct, and that their bodies were ‘cast God wote where‘.

Read More:

Did the Princes Survive? Richard III and The Princes in the Tower

History Salon: The Survival of the Princes in the Tower

The Princes in the Tower with Josephine Wilkinson

- After Richard III, is it time to dig up other famous skeletons? History Extra 3rd December 2014 ↩

- Ackroyd, Peter, The Life of Thomas More, Vintage 1999, p. 155 ↩

- Sylvester, Richard S., More, St. Thomas, The History of Richard III and Selections from the English and Latin Poems, Yale University Press 1976, p. 15 ↩

- Maurer, Helen, “Bones in the Tower: A Discussion of Time Place and Circumstance”, The Ricardian Vol IX, No 112, 1991, p. 18 ↩

- Maurer, Helen, “Bones in the Tower: A Discussion of Time Place and Circumstance”, The Ricardian Vol IX, No 112, 1991, p. 17 ↩

- Why the princes in the tower are staying six feet under, The Guardian, 6 February 2013 ↩