Dr. John Ashdown-Hill will forever be linked with King Richard III. Twelve years ago he commenced research on the mitochondrial DNA sequence for Richard III’s sister, Margaret of York. After publishing his findings in 2006, his research led to the discovery of King Richard III’s grave in 2012. Three years on Richard III will be reinterred in Leicester Cathedral, in an unprecedented week of ceremony and commemoration of his life.

John has one final gift for Richard III. In addition to the funeral crown he has commissioned for Richard III’s reinterment ceremony, John has again commissioned jeweller George Easton to create a rosary that will be placed in Richard III’s coffin when he is reinterred.

“We have lots of evidence that Richard III was a prayerful man”, John told us. “And also specifically that he was concerned with prayers for the dead – both for his dead relatives and for himself, when he died. Therefore I’ve been concerned from the very beginning of the Looking for Richard Project that his remains, if found, should be treated as he would have expected. It distresses me very much that no-one at the University of Leicester (which laid claim to all responsibility for the bones) seems to have any respect for, or understanding of, what Richard would have wanted – even though actually it’s well documented.”

“Richard’s mother was buried with a Plenary Papal Indulgence, and I explored whether we could get one for Richard III. But I was advised by the Papal Nuncio that it would probably be regarded as inappropriate to issue one at this stage (they are normally granted while the individual is living). So I explored with Leicester Cathedral the possibility of burying Richard with a rosary and with certain relics. The relics I had in mind were a relic of St Francis (because Richard had originally been buried in the Franciscan Priory) and a relic of the Holy Cross.”

“Leicester Cathedral would not agree to the inclusion of the relics. I don’t know why. However, they did agree to accept a rosary. And a rosary is a physical and concrete symbol of prayer, so I was pleased they said yes to that.”

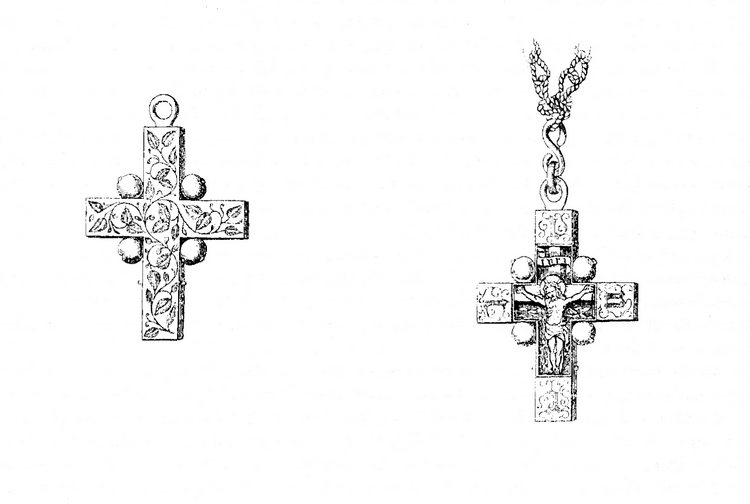

The rosary is one John has owned for many years, and he has added a white enamel rose to represent the House of York and replaced the crucifix with a reproduction of the 15th century “Clare Cross”. The rosary has been blessed at Clare Priory, next to Clare Castle in Suffolk where Richard’s mother Cecily Neville lived. The reliquary was discovered in 1866 when the Great Eastern Railway was building a station and line through the castle. The station closed in 1967, and the castle itself suffered irreparable damage.

The reliquary was discovered by railway workmen in the Inner Bailey of Clare Castle, where the station was being constructed. An article from 1868 described the discovery.

When the men had left their work, part of the glittering metal accidentally caught the eye of the boy, before named ; it lay, in situ, as I am assured, in the gravel of which the mounds are formed, and about 3 ft. from the top of the embankment. This portion of the gravel had not been disturbed by the men ; there was no trace of mixture of any debris from the ancient surface with the gravel, nor of anything, as a box, or the like, that might have inclosed the cross and chain, if they had been hidden in olden times.1

It was previously thought the cross had probably belonged to Philippa of Clarence, but as John suggested in 2006:

Tangible testimony of her [Cecily Neville’s] presence at Clare Castle may survive in the form of a small enamelled gold reliquary crucifix set with pearls, found at the castle site in 1866. This jewel belongs to the second half of the fifteenth century and was therefore almost certainly lost during Cecily’s tenure of Clare. This fact, together with the quality of the workmanship and Cecily’s well-known religious devotion, make her its most likely former owner.2 The reliquary crucifix contains small, carefully wrapped fragments of wood and stone, which are assumed to be a relic of the True Cross, and of the rock of Calvary. This suggests that Cecily Neville may have cultivated a particular devotion to the Holy Cross a devotion which John Howard appears to have shared.3

The enamelling on the original has been lost so the colour is unknown, but jeweller George Easton has used black enamel for the rosary cross.

“We know that Richard III’s family was closely linked to Clare in Suffolk,” John told us. “Miraculously, the priory survives – or at least, was restored. It’s still a house of Augustinian Friars today – and a place I love to go to sometimes for a period of retreat.”

“In the pre-Reformation Priory Church (now a ruin) significant members of Richard III’s family were buried – and still lie. They include Lionel, Duke of Clarence and Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March. And the Castle, next door, was inhabited by Richard’s mother in the 1460s.”

“In the nineteenth century the Clare Cross was found in the castle ruins. It’s actually a reliquary, containing a fragment of the True Cross, and it was probably made soon after 1450 so probably it belonged to Richard III’s mother. For that reason, when I got an agreement from Leicester Cathedral for a rosary to be buried with Richard III I chose a quite large, black wooden rosary which I bought years ago, when I was a student at the University of East Anglia, in Norwich. Then I had the cross and the central link replaced by George Easton (who made Richard III’s funeral crown for me too). George copied the Clare Cross for me, to replace the original crucifix, and he also made an enamelled white rose (like the ones he made for Richard’s crown) to replace the central link. A white rose is the symbol of the house of York, of course, but it’s also a symbol of the Virgin Mary, who is at the centre of the prayers of the rosary.”

Read about Richard III’s Funeral Crown.

You can visit John Ashdown-Hill at johnashdownhill.com and on Facebook at John Ashdown Hill Historian.

- A. Way, ‘Gold Pectoral Cross found at Clare Castle, Suffolk’, Archaeological Journal, XXV, 1868, 60-71. ↩

- Ashdown-Hill J, ‘The Suffolk Connections of the House of York’, Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute for Archaeology & History, vol. 41 part 2 (2006), pp. 199-207. ↩

- Ashdown-Hill J, Richard III’s Beloved Cousyn: John Howard and the House of York, The History Press, 2012, p. 26 ↩