When Richard III decided that his coronation would take place only ten days after the day he had taken possession of the realm by a secular enthronement in Westminster Hall, he would have known that the individuals and institutions responsible for all aspects of the coronation would be under pressure to complete their activities on time. For the Great Wardrobe, responsible for providing the fabrics and garments for the new king, queen and their households, the pressure was even greater, as they had only seven days to complete the making of the royal robes, as well as providing their households with clothing and materials necessary for their appearances at various events and ceremonies.

The Great Wardrobe has a long and interesting history. It had come into existence in the 13th century as a sub-department of the King’s Wardrobe, an administrative department which acted as the financial agent for the royal household. As kings moved around their kingdom, the King’s Wardrobe accompanied them, so it needed places where it could store the heavier and bulkier commodities. Rooms in the king’s manors were set aside for this purpose, as the Wardrobe was responsible for the custody and replenishment of the stocks kept in them. As more areas were set aside for storage, more people were needed to look after the stocks and ensure that they were ready when needed. The Great Wardrobe, therefore, came into being to direct the necessary labour. It was the department of the royal household responsible for sourcing, purchasing, storing and distributing non-perishable items. These items included cloth; furs; spices; electuaries (medicinal substances) and wax. Clerks and staff routinely attended fairs and markets for purchasing, and were responsible for the storing of goods until needed. 1 The Great Wardrobe was also responsible for military requirements, including tents, saddles, bridles and armour.

The term ‘Great’ did not refer to the status of the office, which was ranked below the King’s Wardrobe, but to the size and quantity of goods stored. But the Great Wardrobe was not simply a depository, in addition to collecting, safeguarding and distributing goods, it also manufactured them.

There were a number of officials attached to the Great Wardrobe, including the King’s Tailor, who was responsible for making most of the king’s clothing and furnishings. Other members of the royal family had their own tailors.

Another official was the King’s Armourer, who was responsible for buying, making and maintaining the king’s armour. Strangely, this official was often responsible for embroidery. At first glance, this may seem a rather odd area for the King’s Armourer to be involved with, however this probably came about because of his responsibility for the making and embroidery of flags, pennants and banners. There are later references to him overseeing the embroidery of garments.2 By Richard III’s reign, however, much of the work of the King’s Armourer had moved to the Tower, but some aspects remained with the Great Wardrobe. The post of King’s Embroider, for example, was established in the reign of Richard II.

In addition to its permanent staff of craftsmen and women, the Great Wardrobe also employed artisans and other skilled workers as the need arose.

Originally the Tower of London was selected as its first centre, but the quantity of goods that it became responsible for required additional accommodation. By the 14th century, houses in the City of London were also used. In 1361, larger and better quarters were bought in the parish of St Andrews, by Baynard’s Castle, which remained its home until the Great Fire of London in 1666.3 Modern London retains a memory of the Great Wardrobe as the site is known today as Wardrobe Place and the nearby Parish Church is still known as St Andrew-by-the-Wardrobe.

There is little doubt that the Great Wardrobe would have been preparing for the coronation of his successor since the death of Edward IV, purchasing bolts of cloth and other essentials. However, there is a significant difference in the requirements for a coronation of a boy king, with presumably a smaller royal household, to those of an adult king with a queen who had a household of her own to be equipped. Considerable extra work would have been needed, more craftsmen and women hired and further materials purchased.

In Anne F. Sutton and P.W. Hammond’s seminal work on the documents associated with Richard’s coronation, the authors traced a number of documents associated with the work of the Great Wardrobe in providing the necessary materials and clothing. For example, they traced the indenture, that is, the order from the royal household, as well as the list of items actually supplied. When comparing these lists with the Little Device (the Coronation programme of 1483), some discrepancies are evident which Sutton and Hammond speculate may reveal the personal preferences of Richard III. One example concerns the king’s doublet which he wore for the Vigil Procession, the day before the coronation. A doublet of green or white cloth of gold damask was specified, but Richard actually wore blue cloth of gold wrought with nets and pineapples. 4

There is also a record of an exchange of gifts between Richard and Anne. He gave her four yards of purple cloth of gold, twenty yards of the same wrought with garters and a further seven yards of purple velvet. She gave him a gift of enough purple velvet with garters and roses to make a long gown, lined with eight yards of white damask.5 Although this may conjure up a picture of the two of them happily sorting through the fabric stores, tossing out their choices from the piled up stock available into the arms of waiting servants, it is more likely to have been organised by officials.

The Great Wardrobe did not just have responsibility for supplying fabrics and clothing. It also acted, in modern terms, rather like a set dresser to ensure that the areas where various ceremonies were to take place emphasised the king’s wealth and power. This included supplying suitable pieces of furniture, cloth of gold for draping various surfaces, including royal seats, and providing richly embroidered cushions where necessary. It also provided the woollen cloth the monarch walked on from Westminster Hall to the Abbey.

The Great Wardrobe also had regard to the comfort of the king and queen during the long coronation ceremony. Two closets were constructed near to the altar and shrine of Edward the Confessor in the Abbey itself, where the king and queen could change their robes out of sight of the congregation and also, if needed, break their fast. These closets were curtained and contained chairs and cushions.

When it came to the coronation itself, the work of the Great Wardrobe was crucial. It not only supplied the complicated robes of the king need for his anointing, but also the canopy held over his head, the cotton to wipe up surplus oil, the coif and gloves, to protect the anointed places, the tunic shaped like a dalmatic (a long, wide-sleeved tunic, which serves as a liturgical vestment in the Catholic and other churches,) and the sabatons of gold tissue (A sabaton is part of a knight’s armour that covers the foot. In the fifteenth century they typically ended in a tapered point well past the actual toes of the wearer’s foot. This does not mean that Richard wore armour at his coronation, merely that his footwear mimicked armoured footwear.).6

The Liber Regalis provided for two sets of clothing for the king – crimson for his anointing and purple for crowning. Despite the fact that the book specified only one set of clothing for a queen consort, it was decided that Queen Anne would also have two sets of clothing, like her husband. These provisions regarding colour broadly apply to modern coronations. In 1953, although her gown was white and gold, Queen Elizabeth II entered Westminster Abbey with a train of crimson velvet and left after her crowning with a train of purple velvet.

As the ceremony required the king to be anointed in several places, including his shoulders and breast, some people have assumed that he would need to remove his clothing for this to happen. In fact, both sets of crimson garments were made with specially arranged slits so that the king and queen could be easily anointed in the various places required.

The documents set out what was required for each set of clothing, although it is quite difficult to visualise what they looked like. There are illustrations, for example from the Rous Roll, which appear to show Richard and Anne at their coronation. However, the illustration of Richard shows him in armour, which we know he did not wear. The illustration also shows the queen wearing robes patterned with her coat of arms – again, this is not what she wore at her coronation.

This is a description of the crimson robes prepared for Anne and used for her entry to the Abbey and her anointing.

‘To oure said souverain Lady the Quene forto have unto her mooste honourable use ayenst the same her mooste noble coronation:

A robe of crymysyn velvet conteignyng mantel with a trayne, a surcote and a kyrtell made of xiviij yerdes of crymysn velvet. The said mantel with a trayne, surcote and kyrtel furried with Cxxj tymbr’ of wombz of menyver pure and the surcote garnyssht with oon unce j quarter ryban of gold of Venys. And the saide mantel garnyssht with a mantel lace of silk and gold with botons and tassels of silk and gold. And forto make of iij panes for iij roobes vj yerdes of white fustian. And for the kirtil of the saide robe lxx annlettes of silver and gilt. And for the lace with the kyrtels of her roobes iiij agelettes of silver and gilt. And forto make with the same robe oon unce di. of silk.’

Her purple robes were described as:

‘A robe of purpul velvet conteignying a kyrtel, a surcote overt and a mantel with a trayne. All iij garments made of lvj yerdes of purpul velvet. The sayde surcote overt furried with iij tymbr’ di. and v ermyn bakkes and viij ermyn wombes. The said furre powdered with CCCCxxv powderinges made of bogy shankes. And the said furre bynethe parfourmed with xxxij tymbr’ of wombes of menyver pure. And the said mantel furrid with xxj tymbr’ di of ermyn bakes and powdered with viijMD powderinges made of bogy shankes. And the said kyrtell lined with iiij elles of Holand cloth and garnissht with lxxv annlettes of silver and gilt. The saide mantel garnyssht with a mantel lace of silk and gold with botons and tassels unto the same. And the same robe garnissht with oon unce of ryban of gold.’7

We do know that the queen’s train was not as long as that worn by Elizabeth II, as only one person was needed to carry it – Lady Margaret Beaufort.

The documents record the clothing made for the king, amongst which were the following:

‘Two shertes…of sarsynet crymysyn, boothe open afore and behind, under the breste deppest, bitwene the shulders and in the shulders and bitwene the binding of the armes, for his inunccion.’

‘A large breche myd thigh depe, losen afore and behind, made of half a yerde of sarsynett bounde with a breche belt …of crymysyn velvet.’

‘A payre of hosen made of a yerde and a quartr of crymysyn satyn lined with a quarter of a yerde of white sarsynett.’

‘Roobe of crymysyn satyn to be anonted in conteignying a coote, a surcote cloos, a long mantel and a hoode …all made of rede satyn. The said mantel furrid with wombes of menyver pure and garnyssht with oon unce of ryban of gold…by the coler and laced afore the breste with a longe lace of red sylk…with tassels of rede sylk and gold…The said hoode furred with …erymyn bakkes and…erymyn wombes.’

‘And a coyfe made of a plyte of lawne to be put on the Kynges heede after his inunccion and soo to be kept on by viij dayes after the Kinges coronation.’ (This was an object of special significance, King John, for example, was buried in his, his body wrapped in his coronation robes. 8

‘A robe of purpul velvet conteignying vj garments, that is to wit, a kyrtel made of…purpul velvet furred with….wombes of menyver pure and the labels of the same tabard purfiled with….newe ermyn bakes

A surcote overt made of…purpull velvette furred with….ermyn wombes.’

‘A mantel with a trayne made of…purpul velvet furried with….newe ermyn bakes and powdered with….powderings made of bogy shankes.’

‘And a cappe of astate made of half a yerde of purpul velvet and furred by the roll thereiof with…new ermyn bakes and powdered……with bogy shankes.’

‘A bonnet made of iij quarters of a yerde of purpull velvet.’ 9

Although it is possible to understand much of the descriptions, there are some terms which are unfamiliar. Happily, Sutton and Hammond provided an extensive glossary, from which the following has been extracted:

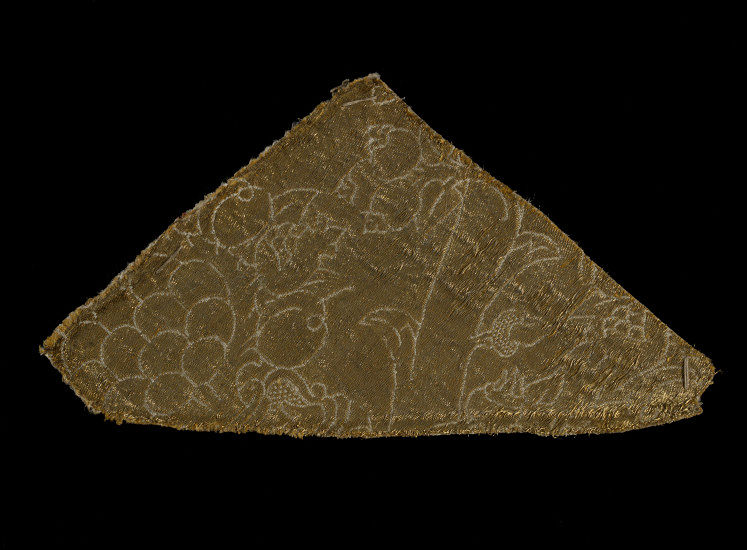

Cloth of gold/silver: A fabric consisting of threads, wires or strips of gold/silver interwoven with silk or wool

Fustian: A coarse cloth of cotton and flax, originally from Forstat, Cairo.

Scarlet: An expensive, fine wool cloth, not necessarily scarlet in colour.

Annelette: A little ring though which laces can be threaded.

Bogy Shanks: Leg pieces of imported lamb skins originally from Bougie.

Menever/menyver: Miniver – fur made from the white belly skins of Baltic squirrels.

Kirtil/krytel: In the 15th century, often made with long, tight-fitting sleeves and worn under other garments.

Mantal: A cloak.

Mantal lace: Elaborate cords for tying mantals across the breast.

Lace: A cord for tying garments together, often by threading the cord though eyelets

Powdered: Sprinkled, especially to describe ermine skins with black ‘tails’

Powderings: Items sewn to a garment to give a powdered/sprinkled effect

Pineapples: A decoration of pinecones frequently used on cloth at this date

Wombz/wombes: Belly

10

In addition to the clothing for the royal couple, the Great Wardrobe also made clothing for the lords spiritual and temporal, including the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishops of Durham, Bath and London as well as the Lord Treasurer, the Chief Justice, and many other officers of the royal household.

The ladies were not forgotten. Records show deliveries of scarlet to the duchess of Suffolk, the two widowed duchesses of Norfolk and the current duchess, the countesses of Richmond, Surrey and Nottingham as well as Ladies Lovell, Fitzhugh, Scroope and Mountjoy.

Ladies also received ‘divers clothes of golde and divers sylke’. Among the list, the Duchess of Suffolk received a long gown of blue velvet and crimson cloth of gold. The elder dowager duchess of Norfolk received a long gown of blue velvet and white cloth of gold, whereas the duchess of Norfolk received a long gown of blue velvet and crimson cloth of gold. The Countess of Richmond received a long gown of crimson velvet and white cloth of gold.11

In addition to information about the materials supplied, the documents also record payments to various people working in the Great Wardrobe as well as those employed to deliver ‘…divers roobes and garments….’ The Accounts of 1483-1484 contain information about payments to the people who made the garments or decorated them. Just two examples from the accounts will illustrate the fascinating detail contained in them. The first is ‘Alice Claver, sylkwoman for pointing of xxij dosen poyntes of ryban of sylk , for pointing of every dosen ij (that is one penny). Her total came to iij s. viij d (that is two shillings and seven pence). Alice is also recorded as being paid for other work relating to laces of Venice silk, other mantel laces and making fringes of Venice gold. For each element of her work, the document lists payment for producing one, and then her total payment.12

The second is William Melborne recorded as receiving 10 shillings and 3 pence for gilding the staves used to support various canopies. He was also paid 10 shillings and nine pence for ‘sowing, gourlying and frenging of a banner of Saint George armes’. 13

With only a relatively short time to provide all the things necessary for Richard’s coronation to demonstrate not only the king’s wealth and power, but also the efficiency of the Great Wardrobe, it would seem that everything largely went to plan. As far as is known, there are no records which would indicate that Richard’s coronation did not live up to expectations or that the materials and clothing supplied did not provide the great spectacle that he wanted.

- ‘The Great Wardrobe’ Lexis of Cloth and Clothing in Medieval Royal Wardrobe Accounts website<https://medievalroyalwardrobelexis.wordpress.com/the-great-wardrobe/> accessed April 2020. ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, William Benton, London, Vol 23, 1962 pp. 349-35. ↩

- Hammond, PW, & Sutton, Anne F., The Coronation of Richard III: the Extant Documents, Alan Sutton, Gloucester, 1983 pp. 74-75. ↩

- Ibid p78 ↩

- Ibid pp. 76-77. ↩

- Ibid p. 163 ↩

- Church, Stephen King John; England, Magna Carta and the making of a Tyrant Pan Books 2016, p. xxiii. ↩

- Sutton and Hammond, Op Cit p. 157 ↩

- Ibid pp. 416-435 ↩

- Ibid pp. 167–169 ↩

- Ibid pp 131-132 ↩

- Ibid p. 137 ↩