Captain James Cook first encountered the Aboriginal people of Australia in April 1770 and was immediately struck by their vigorous good health, their cleanliness and their innocent lack of interest in material possessions of any kind. Cook was on a mission, ostensibly to record the transit of Venus, but in actuality as an eighteenth-century English explorer seeking to find and explore new lands and, perhaps more importantly, claim these new territories in the name of King George.

Naturalists, botanists and surveyors set out from England aboard armed ships in order to scientifically record species of new animals, new plants and new societies and the make-up of Cook’s compliment aboard his ship Endeavour fulfilled this criteria admirably.

Before setting sail from England Cook had been warned by the president of the Royal Society in London to remain patient with any natives he encountered and that he should always remember that “shedding one drop of the blood of these people is a crime of the highest nature… they are the natural, and in the strictest sense of the word, the legal possessors of the several regions they inhabit”. As such these people had the natural right to repel invaders and, given that Cook had secret orders to claim these new lands for king and country, made a glaring inconsistency between the rhetoric of the Royal Society in respecting the natural inhabitants of any newly discovered lands and the reality that would undoubtedly ensue in claiming these lands for Britain. Cook, along with all other explorers of new lands, was therefore always obliged to answer the ultimate question of conquest: To understand other people and places; or to possess them?

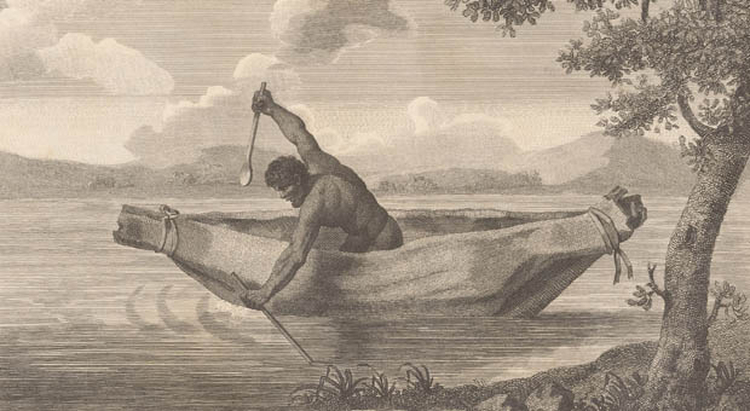

Before the arrival of any European ships, native Australians lived in some two hundred and fifty nations, each with its own subtly different language, and composed of subsidiary tribes; they had a political system similar to that of native Americans and to the Europeans in their hunter-gatherer phase. Australian hunter-gathering had not developed into farming, the soil being mostly thin and lacking the necessary grasses and vegetables to develop. Instead they used fire-stick cultivation, burning back undergrowth to allow new growth; and had begun systems of canals, fishing-traps and winter settlement villages – and all this before the British invasion.

With Cook, on board the Endeavour, was the aristocratic botanist Joseph Banks who had previously immersed himself into the customs and rituals of the islanders of Tahiti (from where Cook had now sailed to Australia) and who could be considered as a radically open-minded product of the Enlightenment. Cook, Banks and the ship’s officers first contact with the Aboriginal people of Australia was cautiously friendly, despite the fact that it was hard for them to make themselves understood. As a consequence of this language barrier they found it impossible to trade with these good-looking, fit young men who patrolled the beaches and who were scarred from fighting but appeared to be free of any disease. Banks, who had learnt to speak some of the Tahitian language during Cook’s three month stay in Tahiti, contented himself on this occasion with merely collecting specimens from this balmy and almost empty land, which contained an abundance of unknown plants and animals, many of which hopped, much to Banks’ puzzlement. Cook eventually christened his anchorage Botany Bay in deference to the extent of the collection that Banks accumulated.

This landscape would stay in Banks’ mind long after his arrival home, because he was a farmer as well as a botanist, and he believed that the soil and water of the land he had explored could be easily cultivable by European farmers in order to support oxen and sheep and to grow wheat.

Back in Britain things were beginning to change. The ancient life of the peasants, tending common land, gathering firewood, killing game and feeding their own animals, was finally ending. A newer, more efficient way of farming would help to feed the new factory communities, but would also drive huge numbers of the poor into already overcrowded cities. Faced with starvation, many turned to petty crime in a desperate attempt to survive. At one point some 220 crimes were punishable by hanging, many of these capital crimes were for petty theft and even children were not spared this ultimate sanction in merely seeking to avoid death by hunger.

Public opinion eventually became somewhat uneasy about the practice of killing the poorest, including the hanging of children, even for the smallest theft. To many, transporting the convicted felons by boat somewhere else seemed the humanitarian alternative. This was the perfect solution, as it not only allowed the privileged classes to salve their consciences, but also dumped the unwanted dregs of the population as far away as possible. The ultimate literalism of the saying; out of sight, out of mind.

Before the loss of Britain’s American colonies, some sixty thousand felons had been sent there to work on the land until such time that they had earned their freedom. Once American independence closed this option off, prisoners were instead held in disgusting dis-masted old hulks off the Thames, which was both a dangerous and impractical solution. With the jails festering, filthy and overflowing and public opinion against mass hangings continuing to grow, another alternative had to be found, and found quickly.

Banks, by now a member of the King’s Privy Council and personal advisor to George III on his Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, suggested Australia and, given his status and the dilemma now facing the penal system, parliament was happy to endorse and ratify his suggestion.

Banks believed that in Australia, just as they had done in America, British felons could make the land flower, and then ultimately enjoy the freedom that their labours had earned. Unsurprisingly, Botany Bay was chosen as the destination for this venture into a second New World and so, in May 1787, the First Fleet of eleven ships, carrying 775 convicts – 192 of them women – plus 645 soldiers, officials and family members, set out on the gruelling and dangerous thirty-six week journey to Australia.

When the first European ships arrived off the coast of Australia the indigenous population thought, them to be floating islands inhabited by the white-skinned ghosts of their ancestors. The long hair of the sailors and the wigs of their officers made them appear as women to the Aboriginals and it was necessary for some of the sailors to drop their trousers in order to prove that they were male. The Aboriginals then offered them women in the hope that, satisfied, they would leave. Their innocent incomprehension of the situation that was unfolding in front of them was vaster than the oceans that separated these people.

In charge of the First Fleet was an admirer of Banks, the professional seaman Arthur Phillip.

After the arrival of all the ships in the fleet by 20th January 1788, Phillip quickly realised that Botany Bay was considerably less inviting than its name suggested, and transferred the new colony to nearby Port Jackson, naming the cove Sydney, after Lord Sydney, the home secretary.

On the 26th January 1788, Phillip raised the Union Flag on the new beachhead and formally claimed possession of this new territory in the name of King George III.

It was apparent at the outset that the native population was unfriendly as the settlers were greeted with cries of “warra, warra, warra”, meaning “go away, go away, go away”. Largely ignoring this obviously hostile reception, the British began work on their settlement, commencing with the building of huts and basic living quarters. This did not go down well with the native clans of the Eora, who had a population of some fifteen hundred people already living in the area, and they subjected the colonists to periodic attacks and sustained harassment.

Phillip, like Banks before him, considered himself a modern Enlightenment man and had no intention of merely running a vast prison. He insisted on the eventual emancipation of the convict settlers, promising that there would be “no slavery” under his command. Life was tough, however, as the unwilling farmers initially had to survive on the rations that they had brought out with them and many of them had to be harangued and lashed to encourage their endeavours, with an occasional hanging thrown in as an added incentive to diligent toil.

Slowly, they learnt to cultivate the land and tend to the livestock that had also accompanied them on their voyage from England. Parliament, rather more concerned with the wars with the French, put a low priority on resupplying this colony, but eventually supply ships and further fleets containing more convicts arrived, and the colony grew.

The attacks on the colony from furious and puzzled Aboriginal locals continued, but Phillip wanted them well treated. Kill them and you will hang was an order that applied to the soldiers as well as the settlers. Phillip’s direct orders from the king were that he “endeavour, by every possible means, to open an intercourse with the natives, and to conciliate their affections, enjoining all subjects to live in amity and kindness with them”. This would have been fine and dandy under a reciprocal trading arrangement, but the British had simply sailed into and taken over the Aboriginals’ excellent harbour and fishing grounds and were now extending their settlement inland, provoking rage and bewilderment in equal apportionment. Marine captain Watkin Tench wrote that they “seemed studiously to avoid us, either from fear, jealousy, or hatred. When they met with unarmed stragglers, they sometimes killed, and sometimes wounded them”. Over time Tench came to think that the Aboriginals were in fact people of “humanity and generosity” who were only responding to “unprovoked outrages” by the whites. A system of communication had to be opened up if Phillip and his officers were to have any chance of bettering relations between the colonists and the natives. He regarded it as imperative that he explain to them that the British had arrived peacefully, but for good, and that the attacks upon colonists and theft of supplies and equipment had to stop.

Phillip needed a translator, so he set about finding one in the only way he deemed possible at the time – he instructed his officers to kidnap one.

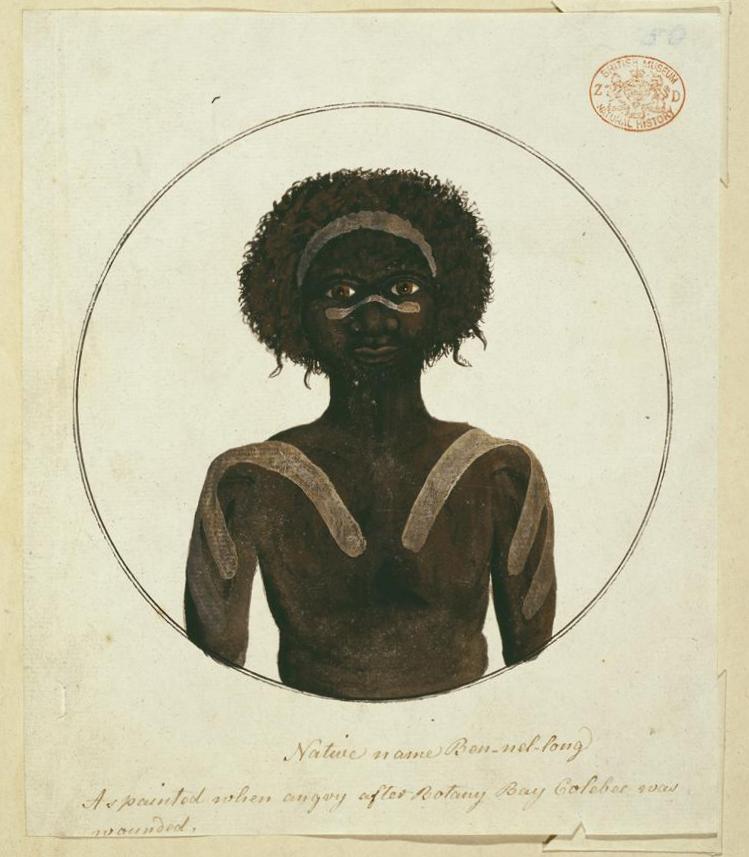

Using fish as bait, the colonists managed to lure two natives into the shallow waters close to a boat filled with soldiers. Upon taking the bait the natives were immediately seized and shackled, although one managed to escape relatively quickly. The other, Woolawarre Bennelong, would learn English, be taught to dress in thick cloth and leather, with buttons and buckles, and would even visit English spa resorts and London itself, including the House of Commons, before returning to Australia.

He had been seized in the hope that the British colony in what is now Sydney might communicate with the Aboriginal people, and that both sides could come to a greater understanding about their vastly different cultures. Bennelong was amazingly scarred. Most of these scars were from spears and he also had half a thumb missing, but he also carried the scars of smallpox; another gift from the European settlers who had also taken his lands and now his liberty.

Bennelong stayed with the colonists for six months and developed a close relationship with Phillip, now firmly established as governor of the British colony, calling him “father”, before eventually disappearing back into the bush. Once free, he persuaded Phillip to come and meet him and his people, the Wangal clan, in order to celebrate the grounding of a whale. Once there, Bennelong had the governor speared in the shoulder by a “wise man” of the clan. This was probably in the manner of an honour punishment for wrongdoing and was a traditional Aboriginal custom as a form of retribution. Phillip’s wrongdoings would have included the theft of fish, game, weapons, nets and land; of building a settlement without permission; the random shooting of natives; the curse of smallpox; and the mysterious genital infections of women that were now spreading to the men. Phillip recovered from his serious wounds and, showing remarkable understanding, ordered that there was to be no retaliation and eventually repaired his friendship with Bennelong, which oversaw a period of better relations between colonisers and natives. This however, would not last for long.

Phillip returned home in 1792 and Bennelong went with him. When Bennelong was paraded around the social circuits of London and the provincial towns he failed to attract the attention that earlier “savages” had. It seems that the idea of “the noble savage” had passed its time and, in any event, people regarded the territory of New South Wales as a grimly practical dumping-ground for unwanted Britons, rather than some kind of exotic paradise.

Bennelong’s story showed how European attitudes to “savages” had changed in a short space of time. When Cook and Banks had first encountered the Aboriginal tribesmen they admired them and they fitted perfectly into a key idea of the Enlightenment; that of “the noble savage”. Bennelong’s lust for women of rival tribes – a reason for many of the spear marks on his body – and his readiness to use violence were a sound warning against such idealistic stereotyping, but the speed of the change in European attitudes towards the indigenous natives of far away lands was both shocking and contemptuous. In a little over twenty years since Cook’s discovery of Australia and Phillip’s return home, the notion of “the noble savage” was fast being abandoned for racist contempt, and before long, far from being a proud alternative to civilised Christians, or indeed as being seen as a dangerous threat, Europeans were seeing natives as subhuman, and even hunting them for sport. The Enlightenment’s admiration for hunter-gatherer people, living without clothes or hypocrisy, had not taken too long to warp into colonialist contempt.

The naked people so admired by Cook for their simple honesty had been forced off their lands simply because Britain needed somewhere to dump her thieves, many of whom had also been ousted from their natural environment due to Britain’s greater industrialisation and the greed of many factory and mine owners.

In Australia, some Aboriginals turned to open revolt. One of them, Pemulwuy, made a final stand in 1797; he was shot seven times and captured. He managed to escape with a manacle on his leg, but was eventually killed in 1802. His severed head was sent to the collection of that great lover of Australia, Sir Joseph Banks.

For the eighteenth-century European explorers, the noble instinct and the greedy one often became inextricably linked. Pemulwuy was but one of the many victims of European settlement, but the most prominent victim of colonisation and its lasting effects would be Enlightenment optimism.

As for Bennelong, he continued as an adviser to the British, and learned English well enough to write to Phillip and his family in Britain. He retained a powerful Aboriginal position and, after his return to Australia, became the clan leader of some hundred people. Bennelong often took part in “honour fights”, involving spears being thrown at men who had to hold their ground with shields, and ended up as a respected elder. However, as the colonists took more land, relations with the native people deteriorated and the notion of some kind of peaceful coexistence or friendship collapsed. Bennelong died, aged fifty, possibly from drinking too much alcohol, but still admired by his own people.

Colonisation heralded the end of a way of life for the Aboriginal tribesmen; with the death of many of them, the loss of their lands, and the complete destruction of a way of life that had developed over many thousands of years.

Banks and Phillip were honourable, decent men who genuinely tried to do their best in integrating two diverse peoples into a harmonious union. This was always going to prove impossible as the overriding priority was to claim these new territories for Britain and this was always going to be detrimental to the indigenous peoples of the region. However well intentioned, they remained Europeans, and ultimately saw nothing wrong in taking these lands and claiming them for Britain. The Aboriginals could therefore live under Britain’s terms or not at all, and yet this paradox of conquest was never questioned by these gentlemen of the Enlightenment, who undoubtedly believed that the Aboriginals’ integration into the British Empire would enhance their race, rather than destroy it.

Colonisation was in the end about force, not friendship.

All source material and extracts from:

Marr, Andrew A History of the World Macmillan 2012.

Invasion Day 1 by Gordon Syron.

Banished a new BBC drama series by Jimmy McGovern, is inspired by the events of the late 1780’s when Britain deported its unwanted citizens to the very edge of the known world. The first episode of this seven-part drama will air in the UK on the BBC on Thursday, March 5th

Read More:

BBC’s Australian Convict Drama Banished

Neil Kemp is a keen and passionate amateur historian and prize winning photographer who lives in Margate, on the North Kent coast in the United Kingdom. Before retiring he worked both with and at Margate Museum, overseeing budgets on a number of historical projects.