The University of Leicester, along with scientists from the University of Cambridge and Loughborough University, have finally released their case report on King Richard III’s spinal condition. The study, titled The scoliosis of Richard III, last Plantagenet King of England: diagnosis and clinical significance, was published today in the scientific and medical journal, The Lancet.

The findings now confirm what many of us have been speculating on since his remains were discovered. “The physical disfigurement from Richard’s scoliosis was probably slight since he had a well balanced curve. His trunk would have been short relative to the length of his limbs, and his right shoulder a little higher than the left. However, a good tailor and custom-made armour could have minimised the visual impact of this.” The report also confirms that Richard suffered from idiopathic scoliosis, which likely started after ten years of age. As to whether it affected his ability on the battlefield the report states “a curve of 70–90° would not have caused impaired exercise tolerance from reduced lung capacity, and we identified no evidence that Richard would have walked with an overt limp, because the leg bones are symmetric and well formed.”

Most Richard III enthusiasts will not find the results particularly surprising, it has always been assumed his Shakesperean deformities were exaggerated or invented. Richard’s scoliosis was never really commented on in his lifetime. Scoliosis was probably as common a condition then as it is now, comparatively. Historian Leanda De Lisle thinks it may have been hereditary in the house of York. In her latest book, Tudor The Family Story, she writes “Scoliosis is often the result of a hereditary condition, so it may be relevant that not only was Richard’s great-great-nephew Edward VI described as having one shoulder higher than another, but also that his great-great-great-niece Lady Mary Grey may have had a more severe skeletal deformity”. Lady Mary Grey suffered from severe kyphosis. There are contemporary accounts of both Mary and Edward’s conditions, Mary was referred to as “crook backed and very ugly”.

Edward’s condition is described by the Imperial ambassador Jehan Scheyfve in a letter to the Bishop of Arras.

“the King of England is still confined to his chamber, and seems to be sensitive to the slightest indisposition or change, partly at any rate because his right shoulder is lower than his left and he suffers a good deal when the fever is upon him, especially from a difficulty in drawing his breath, which is due to the compression of the organs on the right side. It is an important matter for consideration, especially as the illness is increasing from day to day, and the doctors have now openly declared to the Council, for their own discharge of responsibility, that the King’s life is threatened, and if any serious malady were to supervene he would not be able to hold out long against it.

Some make light of the imperfection, saying that the depression in the right shoulder is hereditary in the house of Seymour, and that the late Duke of Somerset had his good share of it among the rest. But he only suffered inconvenience as far as it affected his appearance, and his shoulder never troubled him in any other way. It is said that about a year ago the King overstrained himself while hunting, and that the defect was increased. No good will he ever do with the lance. I opine that this is a visitation and sign from God.” see Calendar of State Papers, Spain, Volume XI 1553, February 17th

There are several interesting points in this letter. Scheyfve discusses Edward’s shortness of breath in relation to his condition, one of the symptoms of scoliosis. Scheyfve also mentions it is hereditary in the house of Seymour, and that Edward “overstrained” himself while hunting which worsened his condition. John Ashdown-Hill explores this in relation to Richard’s condition in his latest book The Third Plantagenet, speculating that the onset of Richard’s scoliosis may have been caused by physical trauma.

We know that Richard’s physical appearance has been exaggerated, and we can see that scoliosis was a known condition and a common enough one not to cause much comment. Certainly it wasn’t remarked on in Richard’s lifetime, but by later writers, who were obviously using it as an insult, or in more sinister cases, as proof of his villainy. It was not at all uncommon for later writers to seize upon minor physical blemishes and twist them to suit their monstrous imagery. When we look at the case of Anne Boleyn who may have had a minor ridge on the nail of her pinky finger, which in the gossip of her detractors manifested into a sixth finger, a story that was exaggerated and embellished so that even wearing long sleeves was supposedly to hide her deformity and high collars to conceal her “witches teat” we can see how this imagery evolves.

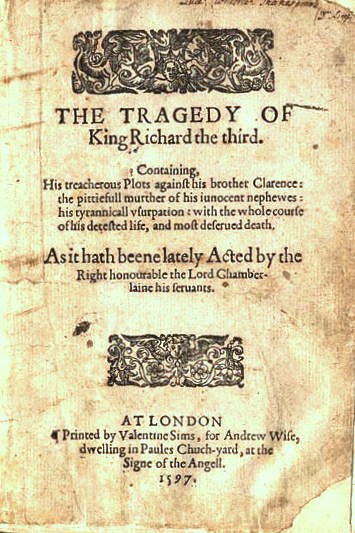

Still, Rous, More and Vergil had only referred to Richard as “crookback” – leaving aside Rous’ outrageous depiction of Richard’s birth – they unflatteringly referred to his scoliosis as a deformity. But it was not until more than a hundred years later Shakespeare would create the “bunch-backed toad” with the “blasted sapling”, the limping hunchbacked villain.

The first time I saw The Tragedy of Richard III I assumed it was a satire. Yet of course the play influenced later writers, then early historians, who in turn influenced historical fiction. We can see how the villainous image of Richard has evolved. But Shakespeare didn’t just use More or Holinshed’s depictions of Richard’s alleged crimes, he expanded on them. What exactly was the Bard’s motive?

If you view The Tragedy of Richard III as a morality tale, much like Thomas More’s King Richard III was a warning against tyranny rather than an actual history, you can consider one of two theories. There is the Oxfordian theory of Shakespeare authorship, that Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, wrote the plays attributed to Shakespeare. Or you could consider the more straightforward theory that Shakespeare himself was using The Tragedy of Richard III as a political satire. In both cases, “Richard III” may actually be an allegory for Robert Cecil, Elizabeth I’s Secretary of State. Cecil was secretly corresponding with James Stuart, the Protestant King of Scotland, and it was Cecil’s efforts that saw James succeed Elizabeth I. Cecil was described as a hunchback. It is possible Shakespeare was using a notorious historical figure to represent someone he could not openly criticise.

Yet the portrait painted over several centuries in a famous play may not easily be forgotten. Now that the case report has finally confirmed that Richard III did not suffer from severe physical deformities will we see a positive effect on his reputation? Will The Tragedy of Richard III be re-written? Tune in on Monday when Philippa Langley will join us to discuss how the public perception of King Richard III has changed since he was discovered after almost five centuries.