The Legend of Richard of Eastwell

Richard, a bricklayer, had arrived in Eastwell in 1542 or 1543 and made his way to Lake House, because he had heard Sir Thomas was building a new mansion and he wanted to offer his services. Sir Thomas’ overseer gave him employment after the usual inquiries about his experience and recent employment. While Richard usually kept to himself, how he spent his leisure time soon attracted the attention of others. Sir Thomas was curious to know why his bricklayer liked nothing more than to spend his time apart from others with a book, and more curious as to why Richard would put the book away when anyone approached him. One day Sir Thomas decided to surprise Richard and snatch his book out of his hands, only to discover that the allegedly humble bricklayer was reading Latin, not the usual sort of reading material among the commoners.

When Sir Thomas asked how he “came by this learning” Richard told him that he had been a good master, and he would trust him with a secret he had never before revealed to anyone. He then told him the incredible tale of his life. He had boarded with a Latin schoolmaster until he was fifteen or sixteen, and a gentleman came once a quarter and paid for his board and see to his needs. Some time after the same gentleman came and told him he must take a trip with him “to the country”. The country was Bosworth Field, where he was taken to the tent of Richard III, who embraced him as his son. Richard III gave his son a purse of gold and bid him hide himself if the Battle was lost. Thus Richard Plantagenet made his way to London, selling his horse and his fine clothes, and apprenticing himself to a bricklayer.

The story has become a local legend in Eastwell. Richard Plantagenet did indeed exist. The parish records showed Richard died in 1550 at the age of 81. So far the obvious has always been assumed that either he was making it up, or that he was an illegitimate son of King Richard III.

But why would Richard III not acknowledge this illegitimate son? He had two illegitimate children, a son and a daughter, that he publicly acknowledged and looked after. Was the mysterious Richard of Eastwell hiding an even bigger secret?

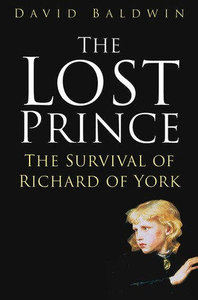

Historian David Baldwin has challenged the identity of Richard Plantagenet, but while David thinks Richard Plantagenet was not the son of Richard III, he does think he had royal blood. David has claimed that Edward V, who had been receiving visits from his doctor before his disappearance, died of natural causes and that Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York, the younger of the famed “Princes in the Tower”, survived. And became “Richard Plantagenet”.

The Princes in the Tower

The story of the Princes in the Tower is one of the greatest mysteries of the middle ages. After Edward IV died, his young son, now King Edward V, was escorted into London by his uncle Richard, then Duke of Gloucester. As was the usual tradition, Edward was lodged in the Tower of London until his coronation took place. But Richard of Gloucester shocked everyone, seizing his nephew’s throne and declaring the marriage of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville invalid, and their children illegitimate.

Elizabeth still had her younger son in her keeping, she had fled to sanctuary in Westminster with the rest of her children. Richard III eventually pressured Elizabeth to give up her son to his safekeeping. She never saw either of her sons again.

Or so we have been led to believe. The story of the young king and prince being murdered was, and is, assumed. There is no evidence. There are no firm contemporary accusations, and moreover, there are no remains. The remains in Westminster Abbey that are alleged to be the princes were found in 1674, in the Tower at foundation level, ten feet down, under a staircase it had taken many workmen several days to dismantle. Hardly the stuff of a hasty burial.

It was never officially declared the princes were dead. Richard III was never accused by Henry VII, Elizabeth of York, Margaret Beaufort or Elizabeth Woodville of having murdered Edward V and Richard Duke of York. The most telling fact is that Elizabeth Woodville made her peace with Richard III. She sent her daughters to stay under his care at court (albeit making him swear a public oath not to harm them) and wrote to her son, who was in exile with Henry Tudor, urging him to make peace with Richard. Why would Princess Elizabeth of York inscribe her name in two books that belonged to her uncle, if she thought he had murdered her brothers?

It was not to either Richard III or Henry Tudor’s advantage to not produce a verdict, or scapegoat, for the fate of the Princes. It led to deep mistrust for Richard, something that factored in his downfall, and for Henry Tudor it gave cause for rebellion. While people thought a Prince of York might be living there was hope. Why did Henry Tudor not bother producing witnesses to identify the pretender Perkin Warbeck as an imposter? Why did he keep such a close eye on the small town of Colchester? Records show that on 31 January 1512 a pardon was granted to a “Richard Grey of Colchester, alias of North Creke, Norf., yeoman or labourer”. Grey was Elizbaeth Woodville’s name from her first marriage, and Richard III referred to her as Dame Elizabeth Grey after he sought to invalidate her marriage to King Edward IV.

Was Richard III innocent of the most heinous crime he was accused of?

If one seeks to exonerate Richard III of the crime of murdering his nephews, rather than look to unlikely candidates for the murder, perhaps we need to take a closer look at the mysterious Richard of Eastwell. The evidence for the survival of Richard of Shrewsbury is far more compelling than any evidence of his murder.

While the residents of Eastwell still embrace the local legend that he was the son of Richard III, they hope the mystery of his existence could be solved with the discovery of Richard III’s DNA. There is a tombstone in St. Mary’s Church is Eastwell that reads “Reputed to be the tomb of Richard Plantagenet”. Councillor Winston Michael, who represents Eastwell and Boughton Aluph on Ashford Borough Council, said he wanted DNA profiling to be used in an attempt to establish who is in the graveyard.

It may not solve the mystery of the true identity of Richard of Eastwell. It could prove whether or not he was of Richard III’s bloodline. The Queen has refused to grant permission to re-examine the urn allegedly containing the remains of Edward V and Richard of Shrewsbury in Westminster. But even if we could prove they were not the remains of the princes, we would be no closer to solving the mystery of their fate than before. David Baldwin told us that more clues have come to light since he wrote The Lost Prince seven years ago, and he hopes to revisit it someday.

Read our interview on Richard III with David Baldwin.

It’s Richard III week. Keep an eye out for more interviews with historians this week in History.

The Lost Prince: The Survival of Richard of York by David Baldwin, published by The History Press 2009.

The Lost Prince: The Survival of Richard of York by David Baldwin, published by The History Press 2009.

Buy The Lost Prince by David Baldwin

Did Richard, Duke of York, the younger of the Princes on the Tower, survive his imprisonment? David Baldwin opens up an entirely new line of investigation and offers a startling solution to one of the most enduring mysteries in English history and a final exoneration for Richard III.