He was the Once and Future prince. The most important boy in all of England, the entire hopes of a new dynasty rested upon Arthur Tudor. He became a bright and beautiful young man who spent his entire life in pursuit of greatness. He was a young scholar, a leader, a lord and a husband. Then his life was snatched from him, and Arthur faded into obscurity. Over the centuries Arthur has become a faint impression, overshadowed by his father Henry VII’s difficult final years as he coped with the loss of his son and wife; outshone by the plight of his fabled princess left widowed and stranded in a foreign country; forever eclipsed by the legendary reign of his tyrannical yet charismatic brother Henry VIII. Arthur is a curiosity, an allegedly frail young man who accomplished little more than being the first husband of the mighty Katherine of Aragon, and whose wedding night would cause centuries of speculation and frenzied debate.

Prince Arthur: The Tudor King Who Never Was tells the story of the real Arthur, an influential figure in his own right, a thoughtful and well-loved young man who was on his way to becoming one of the most important figures in Europe. Dr. Sean Cunningham joins us today to discuss his new book, and the Tudor prince who had the potential to become one of history’s greatest kings.

Your research focuses on the Yorkist and early Tudor reigns, what was it about Prince Arthur that you found intriguing?

Prince Arthur seems to encapsulate the triumph, tragedy and contradictions of the Tudors in one short life.

His parents risked a great deal on his birth but then sent him away to be raised independently. He went on to rule the Marches of Wales as a king-in-waiting, hardly saw his parents, but remained at the core of Henry VII’s hopes for the long-term security of the Tudor royal family and its right to the crown.

Arthur’s marriage demonstrated the wealth and ambition of Henry VII but did not bring him physically into the arms of his family. He was the ultimate Tudor-insider; trained from birth to rule, but he was possibly a virtual stranger to some of his blood relatives. He absorbed his father’s attention and resources yet was also expected to learn how to be a king by ruling in his own right from the age of six (obviously with help).

Arthur’s death was a total shock. Henry VII had complete belief in God’s support and developed no Plan B to build Prince Henry’s skills in case Prince Arthur suffered any mishap. Arthur’s life had been an elaborate training programme in how to become king. His death caused a domino effect of disasters and events that lasted for at least sixty years. Without Arthur, Henry VII came to rely on a harsh and stifling system of rule that was aiming for survival after 1503, rather than anything more ambitious. That change in policy was driving the country towards civil war by the time the king died in April 1509.

Arthur’s life stands in the centre of Henry VII’s reign as the focus for many of the king’s policies and most of his concerns. The fact that Arthur is missing from so many of the narratives of the Tudor period when he had such a prominent role in the first Tudor reign, means that we cannot fully understand how the Tudor century fits together unless we put Arthur back into the picture.

I think that, while the importance of Arthur’s birth is always mentioned, it is still underestimated. Can you tell our readers about the significance of Arthur’s birth and what it meant to Henry VII and Elizabeth of York’s early reign?

Until the marriage of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York produced an heir there could not really be a claim that Lancaster and York had been united. Henry VII knew that he needed an heir but he gambled his crown, if not his life, on his first child being a healthy boy. The court and government moved to Winchester in August 1486 and the city was set up for the birth and christening of a baby boy who would be named after the legendary British king. That was a colossal risk – just like his march across Wales and England to the battle of Bosworth a year earlier.

Henry VII was already facing conspiracy in the royal household and open rebellion in the north and midlands. He needed all of his planning to fall into place to be able to unite the court and the wider political community behind him. The birth of Arthur enabled that to happen. Had events not turned out so strongly in Henry VII’s favour then Lambert Simnel’s serious rebellion of June 1487 would probably have been far-better supported. The kind of inaction and desertion that Richard III had suffered in August 1485 is likely to have been repeated at the battle of Stoke. Such difficulties might have made Henry VII’s reign as short as Richard III’s too. Instead of Arthur becoming a rallying point for the Tudor crown, any other outcome of Queen Elizabeth’s pregnancy might have set Henry VII on course for deposition before his reign had got going.

Looking at the political climate preceding Arthur’s birth and Henry VII’s own formative years, what factors influenced the forming of Arthur’s household?

The king and queen agreed to raise their infant prince in a palace forty-five miles from London, so it might be counter-intuitive to say, but security was probably a primary concern.

Arthur’s birth had fulfilled all of the hopes of King Henry and Queen Elizabeth, although perhaps for different personal reasons – she, that death had not claimed her in childbirth; and he, that Arthur now gave a focus for his regime’s development. Above all, Arthur’s safe arrival can only have confirmed to King Henry that God truly favoured him. An expectation of ongoing divine protection might have convinced the king to take the risk of establishing an independent life for his infant son.

Arthur’s residence at Farnham removed the regime’s heir from the dangers present in a royal household that was itself a melting pot of former loyalties. An act of parliament was necessary in 1487 to improve the policing of crown servants, and its text makes some reference to disturbances and plots that had already arisen. A balance of personnel still had to be found that protected the royal family but also supplied opportunity for former opponents to demonstrate their loyalty to the new king. Removing Arthur from that threat into a separate household made it easier to run his household as a secure institution.

In the first six years of his life, the prince’s residence was transformed from being a nursery into a small version of the king’s household structure. We see the replacement of nurses and cradle rockers with masters-at-arms, sewers and yeomen of the chamber. Even as a child, Arthur was encouraged to take opportunities to learn how to behave as the focus of servants and as a leader in ways that his father had never enjoyed in his own dislocated childhood.

When Henry VII had lived at Raglan and Weobley castles as a ward of the Herbert family, he had very little access to his mother. It is unlikely that Arthur was so isolated. Loss of records hides the details, but it might be the case that Henry sought a balance for Prince Arthur: far enough from London and his family to generate a sense of independence, self-reliance and toughness, but still near enough to have regular visits. The exchange of servants suggests that contact was frequent and performance in post well-monitored.

What do we know about Arthur’s education?

If Bernard André, his main tutor, is to be believed (and he was paid to be a sycophant), Arthur was a prodigious learner. By the age of eleven he was fluent in French and Latin and had learned several classical texts by heart. André used his European humanist contacts to push Arthur’s abilities further. He collected together the latest Renaissance texts – many of them very recent rediscoveries and new printings of Roman and Greek masters like Cicero, Quintilian, Tacitus and Thucydides. André also wrote some glosses and guidance of his own.

André joined Arthur’s household at Ludlow in 1496. Before then, the prince had been taught basic grammar, languages, history and natural science by John Rede, headmaster at Winchester School. Both he and André and bishops William Smith and John Alcock, who led the Council in the Marches, were from the same group of Oxford academics known to the king and Margaret Beaufort. They would have ensured consistency and the most up-to-date classroom education for Henry VII’s son.

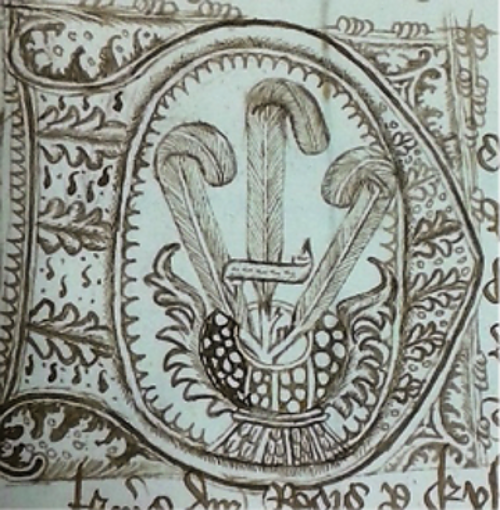

The prince was assigned his own herald -Wallingford- at the age of three when he became Prince of Wales in 1489. That might have marked the start of some basic learning in heraldry, history, genealogy – Arthur’s own family history!

While at Farnham we know that Henry learned to ride and became a fine archer. We don’t know what his physical military training was like but he had impressive armour made for him. His officers and friends could assemble a large army of cavalry, archers and billmen from his marcher estates and he would have learned the skills of leadership (he was probably conscious that many of his predecessors as Prince of Wales had been bloodied in battle before the age of sixteen). Henry VII would not have neglected that side of his learning.

Arthur’s other training that was most relevant to his future role as king would have come from observing and repeating the responsibilities given to his advisers and officials. That was how he would have mastered the application of the law or efficiency in running his manors, woods and estates.

Other skills, like to ability to judge character and personality could only have come from interaction and conversation. So Arthur would also have had an active social side to his education, as seen in the evidence of his numerous visits and travels within the marcher counties.

Because of Arthur’s youth his role as lord of his household is often overlooked. Had Arthur lived after the first year of his marriage, what might some of his continuing responsibilities have encompassed?

Since Arthur’s role on the Welsh Marches was designed to supply him with the broad skills of kingship, it is unlikely that he would have continued there indefinitely once his marriage had settled down. The Council of the Marchers had been re-established before Arthur went to live in Ludlow and continued in the king’s name after Arthur died.

So it seems likely that a period of transition would have commenced with Arthur returning to live in one of the Thames valley palaces near London. That move would have allowed him to integrate himself with the king’s counsellors and familiarise himself with the machinery of central government. Arthur could then have scaled-up the practical and social expertise he had already developed to in the more dynamic world of the king’s household and court.

Part of the plan would have been to welcome a pregnant Princess Catherine; something that would again have changed the dynamics of the regime in a very positive way. Henry VII might then have felt that he could abdicate and pass on responsibility on his own terms to an heir who was fully prepared to rule in his own right.

Arthur is often seen as much younger than his bride Katherine of Aragon, despite being only a year younger, how do you think this idea developed?

Partly because she lived to marry Henry VIII and grow older. Back-projecting Catherine’s life in England made it very difficult to go beyond 1509 because so few people remembered Arthur when he had been alive. By 1530, even the king might have struggled to recall his dead brother. Henry’s role as an eleven-year-old at the wedding festivities of Arthur and Catherine may have been the single occasion when he spent a meaningful period of time with his brother. Thirty years later that memory might have been a little blurred.

The youngest of the men and women who gave statements in 1527-28 at the inquiry into the validity of Catherine’s marriage to Prince Arthur were perhaps in their late-forties. Discussing events that had happened at the very start of the century might have seemed like an age away. Arthur was very firmly part of that period. He would have been recalled as a youth. Because Arthur died, whatever memories people had of him were frozen while the first Tudor prince was a bright-eyed teenager fresh from his own wedding.

Catherine might also have seemed more mature to English observers. At the age of sixteen many girls are more developed than boys of the same age. Historical hindsight over a great span of years makes it equally difficult to pinpoint when puberty ran its course. That could have been a factor in Arthur’s appearance and his behaviour towards his wife in 1501-02. Being only slightly older in 1501 might then have made her appear far more mature than Henry. The fact that she was Spanish, had endured a challenging journey to her wedding, and had brought many novel and surprising practices, clothes, and hundreds of pairs of platform shoes to England, might also have made her seem more exotic and worldly-wise than her husband.

How did the legend of King Arthur inform Prince Arthur’s life?

Just by naming his son Arthur, King Henry made the connection in people’s minds. The prince immediately had an image to emulate. Caxton’s printed version of Mallory’s Morte d’Arthur had appeared the year before Arthur was born. The legendary story would have been fresh in the minds of literate lords and gentry. So Arthur’s training could aspire to turn the prince into a ‘paragon of generosity, affluence, courage, military success, and courtliness’ (ODNB). All were admirable attributes that would have served any king well.

King Arthur’s role in uniting the country in the face of invaders and external threats was also a good point of reference to bring to mind in 1486. Since his father was wily enough to realise that his accession had not ended the Wars of the Roses, Arthur would be presented as a prince who could unite the nation and its people in the face of the king’s enemies; but only if he was supported by all subjects.

The Arthurian connection was also important in attracting support. The Mortimer ancestors of the queen had a very strong tradition of association with King Arthur and the older rulers of Britain. A prince named Arthur who also inherited that ancestry and was also able to claim its support in the Welsh Marches provided a strong anchor for the Tudor crown.

I think that anyone interested in Tudor history will speculate about what sort of king Arthur would have made at some point. Do you think that he is sometimes romanticised in light of his brother Henry VIII’s often tyrannical behaviour?

Arthur’s marriage at fifteen years acknowledged that he was on the cusp of adulthood. Unlike his father, who as far as we know had received no formal training as a leader, Arthur had been learning how to rule from the time that he was two or three weeks old. Although this would have been a gradual process, Arthur lived his entire life in an environment that was set up to provide training in decision-making and leadership.

Henry VII probably wanted his son to follow his example and rule in a similar way. The king’s period of harsh rule, ‘rule by recognisance’ and the rise of powerful but low-ranking ministers did not emerge until Prince Arthur and the queen were dead by 1503.

If there is one thing you would like readers to take away with them about Arthur’s life, what would it be?

The he was on course to be a great king. Arthur had been bred to rule. At a young age, he seems to have mastered many of the mechanical aspects of being a leading noble– managing land and estate officials, running the law in his region, controlling his household and its staff. Unlike the general impression given by some Victorian writers, Arthur was very active and there is no evidence that he was sickly or ill until his final few days of life. He travelled widely and in meeting people he would have learned the inter-personal skills needed to understand and lead life at court. Reports suggest that he was a well-rounded and experienced young man; perhaps a little weighed down by his father’s expectation, but fully prepared for life as king.

His father wanted to pass on the crown in a controlled way. Arthur had been through most of the stages of development that King Henry had planned. After Arthur’s marriage in November 1501, the next stage in this process was for him to become a father. Had that happened, and had Arthur survived his illness at the end of March 1502, then Henry VII could have felt very confident in passing on the crown once his son had reached adulthood.

The period of harsh rule that Henry VII is most notorious for emerged only after Arthur and Queen Elizabeth had died and in response to the dangerous situation that their deaths left him in. Dealing with their loss and the instability that it brought, was partly to blame for the rapid decline in the king’s health and a change in the nature of his kingship from 1504. Had Arthur lived then the king and queen would probably not have felt so compelled to try to have another child. Henry VII might have ruled for longer but with Arthur by his side in the last stages of his training. King Henry’s final years as king would almost certainly have been more harmonious and constructive than they turned out to be in reality.

Henry, duke of York had to step into the role of Prince of Wales; only without a decade a specific education and training for the role behind him. The last years of Henry VII’s reign tried to salvage something from the disaster of family deaths and the loss of experienced allies like Reginald Bray who had held government together. Had Arthur been awaiting his chance to rule then sixteenth century England would have been a very different place to the one we are now familiar with.

Prince Arthur : The Tudor King Who Never Was by Sean Cunningham. Published by Amberley Publishing 2016.

During the early part of the sixteenth century England should have been ruled by King Arthur Tudor, not Henry VIII. Had the first-born son of Henry VII – Arthur, Prince of Wales (1486-1502) – lived into adulthood, his younger brother Henry would never have become King Henry VIII. The subsequent history of England would have been very different; since the massive religious, social and political changes of the Henry VIII’s reign might not have been necessary at all. In naming his eldest son Arthur, Henry VII was making an impressive statement about what the Tudors hoped to achieve as rulers within Britain. Since the story of Arthur as a British hero was very well-known to all ranks of the crown’s subjects, the name alone gave the young prince a great deal to live up to. Through Arthur’s education, exposure to power and responsibility, his key marriage to a Spanish princess, Catherine of Aragon, and his preparation for kingship, did Henry VII hope to shape his heir into a paragon of kingship that all of Britain could look up to? This biography explores all of these aspects of Prince Arthur’s life, his relationship with his brother and imagines what type of king he might have been.

During the early part of the sixteenth century England should have been ruled by King Arthur Tudor, not Henry VIII. Had the first-born son of Henry VII – Arthur, Prince of Wales (1486-1502) – lived into adulthood, his younger brother Henry would never have become King Henry VIII. The subsequent history of England would have been very different; since the massive religious, social and political changes of the Henry VIII’s reign might not have been necessary at all. In naming his eldest son Arthur, Henry VII was making an impressive statement about what the Tudors hoped to achieve as rulers within Britain. Since the story of Arthur as a British hero was very well-known to all ranks of the crown’s subjects, the name alone gave the young prince a great deal to live up to. Through Arthur’s education, exposure to power and responsibility, his key marriage to a Spanish princess, Catherine of Aragon, and his preparation for kingship, did Henry VII hope to shape his heir into a paragon of kingship that all of Britain could look up to? This biography explores all of these aspects of Prince Arthur’s life, his relationship with his brother and imagines what type of king he might have been.

Click here to buy Prince Arthur : The Tudor King Who Never Was with free shipping worldwide

Prince Arthur : The Tudor King Who Never Was available now from Amazon US and Amazon UK

Pictures ©Sean Cunningham. Used with permission. Do not reproduce.

Dr Sean Cunningham, is Head of Medieval Records at the UK National Archives. He main interest is in British history in the period c.1450-1558. Sean has published many studies of politics, society and warfare, especially in the early Tudor period, including Henry VII in the Routledge Historical Biographies series and his new book, Prince Arthur: The Tudor King Who Never Was, for Amberley. Sean is about to start researching the private spending accounts of the royal chamber under Henry VII and Henry VIII for a new project with Winchester and Sheffield Universities. He is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and co-convenor of the Late Medieval Seminar at London’s Institute of Historical Research.