King Richard III has long been a puzzle that history is desperate to solve. His reign only lasted twenty-two months, yet the controversy surrounding Richard III has raged for more than five centuries. It is easy to lose sight of Richard of Gloucester, renounced, reviled, reformed and revered, he remains a mystery. Perhaps it’s time we stopped trying to determine whether he was wholly villainous or completely innocent of his crimes, and accept he was a man as complex as anyone else.

Historian David Baldwin joined us to discuss Richard III, the prince who became England’s Black Legend.

In 1986 you predicted the grave of Richard III would be found at the church of Greyfriars. How did you feel when they finally confirmed the remains found in Leicester were indeed Richard III’s?

I’ve been fascinated by the enigma of Richard III for more than fifty years, so for me it was a truly exciting moment. It is only rarely that an historical mystery is genuinely solved, and I’m delighted that my 1986 article, King Richard’s Grave in Leicester, assisted the archaeologists in their search.

You said that there are too many apparent contradictions in Richard III’s life for him to be neatly pigeonholed as “good” or “bad”, yet this is how he is most often seen, either as Shakespeare’s tyrant or, lately, completely misunderstood and misrepresented. Why is it difficult to accept he had both good and bad qualities?

The problem, I think, is that Richard arouses such passions that it is difficult for both his supporters and his detractors to see him as anything but very good or very bad. My own view is that he was a normal human being who had both virtues and failings, a man who professed high principles but who could not always live up to those principles himself.

Richard was the eleventh child and fourth surviving son of Richard of York and Cecily Neville, so he could not have been expecting to be close to the succession in his youth. If his brother had not captured the throne from Henry VI what might a “normal” life have been like for Richard?

It’s only a guess, but if there had been no civil conflict Richard, as the youngest son, could well have been put to a career in the Church rather than in politics. Abbot Richard? Bishop Richard? Who knows?

Young Richard Duke of Gloucester seemed very concerned about accumulating wealth, sometimes quite ruthlessly, do you think he felt the need to secure his place as he was not looking likely to succeed his brothers and their heirs at that point?

Ownership of land was the principal measure of wealth in the Middle Ages, and every noble and gentle family sought to add to their acres whenever an opportunity presented itself. Richard may have behaved high-handedly on occasion – particularly in his dealings with the elderly Countess of Oxford – but he was doing nothing that the Woodvilles or Warwick the Kingmaker would not have done in similar circumstances. I’ve argued that the upheavals of Richard’s boyhood, his capture at Ludlow, the loss of his father, and his period of exile in Burgundy, had made him acutely aware of the need to watch his back and foster his own interests. If he sensed danger, he struck first.

You discussed how many of Richard’s contemporaries felt about him, do you think any of them were truly expecting him to seize his nephew’s throne after his brother’s death?

Most contemporaries assumed that Richard would govern loyally until his nephew came of age, just as John of Gaunt had ruled for the young Richard II and John, Duke of Bedford for the infant Henry VI. One reason for Richard’s success was that his seizure of power took all but his closest supporters by surprise. Anthony Woodville, Earl Rivers, and William, Lord Hastings were astute and experienced politicians, but both walked blindly into the traps set for them.

Whether or not he ordered the murders of his nephews, some of Richard’s actions during the early period of his reign show poor judgement and he turned many of his nobles against him. Do you think he had a chance of regaining their respect and the love of his people had he not been defeated?

Richard probably calculated that five, ten, or fifteen years of good government would win over all of the doubters and hopefully, most of his opponents, but little could be accomplished in the two years and two months left to him. The tragedy of Richard III is that he had no ‘good’ option – he risked being sidelined if he remained Duke of Gloucester but lost everything by making himself king.

It has been alleged Richard intended to marry his niece, Princess Elizabeth of York, after his wife’s death yet he had declared her illegitimate and she had no wealth or power. Surely a foreign princess would have been a better match? Would there have been any real advantage for Richard in such a match?

Contrary to some arguments, there seems little doubt that Richard was seriously considering the possibility of marrying Elizabeth of York some time before Queen Anne died. She was, of course, his late brother’s eldest daughter and a focus for the loyalty of those Yorkists who had so far declined to acknowledge him; but the problem was that he had previously declared her illegitimate and could not ‘re-legitimate’ her without also re-legitimating her missing siblings, the Princes in the Tower. In the end, pressure from his leading supporters forced him to abandon the idea, and he was seeking a marriage with a Portuguese princess descended from the House of Lancaster when he was killed on Bosworth Field.

As Richard aged he seemed to grow increasingly pious, disdaining the opulence of his brother’s court. Had he lived what do you think court life would have been like during the reign of Richard III?

Richard railed at the immorality of the Marquis of Dorset who, he said, had ‘devoured, deflowered and defiled . . . many and sundry maids, widows and wives’ but he had himself fathered two illegitimate children in his youth. The answer may be that he became more austere as he grew older, and he may have tried to re-invent himself after he became king by setting an example and always doing the ‘right’ thing. There can be little doubt that his court would have been less hedonistic than Edward IV’s.

Your book, The Lost Prince, presents an excellent argument on the possible survival of the younger of the Princes in the Tower, Richard Duke of York. Is it difficult to imagine we are ever going to find any conclusive evidence on the fate of the Princes?

More clues have come to light since I wrote The Lost Prince seven years ago, and it is a subject I would like to revisit one day. The present situation is that if the bones thought to be those of the Princes could be re-examined it might be possible to identify their Y-chromosome which could be then be compared with Richard’s. A match would leave little doubt that they are indeed the missing boys, while a mismatch would leave all other possibilities open – but even a match would not tell us when or how they died.

Thank you for your time David. Is there anything else you would like to add?

Yes, I think Richard should be reburied in Leicester because, as far as we know, no member of his immediate family sought to have his body removed to York (or anywhere else) in the months and years after 1485. And if they were content with the situation, perhaps everyone else should be too.

David Baldwin is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society who devised and taught courses for adults at the Universities of Leicester and Nottingham for more than twenty years. His 2002 biography of Queen Elizabeth Woodville (Elizabeth Woodville, Mother of the Princes in the Tower) has been reprinted many times, and his other books include Stoke Field. The Last Battle of the Wars of the Roses (Pen & Sword, 2006), The Lost Prince, The Survival of Richard of York (The History Press, 2007), The Kingmaker’s Sisters, Six Women in the Wars of the Roses (The History Press, 2009), The Women of the Cousins’ War [with Philippa Gregory and Michael Jones] (Simon & Schuster, 2011), Richard III (Amberley, 2012), and Richard III, The Leicester Connection (Pitkin, 2013).

Read David Baldwin’s original article King Richard’s Grave in Leicester at the University of Leicester website.

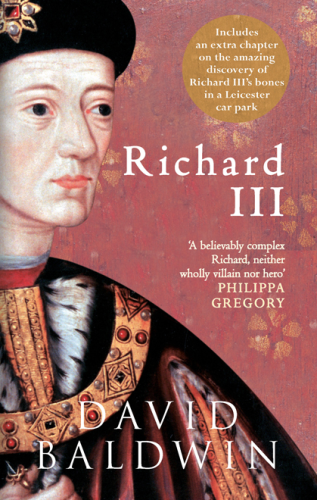

Richard III by David Baldwin, Amberley Publishing

Richard III by David Baldwin, Amberley Publishing

Buy Richard III by David Baldwin.

Not many people would claim to be saints, or alternatively, consider themselves entirely without redeeming qualities. Some are unquestionably worse than others, but few have been held in greater infamy than Richard Plantagenet, afterwards Duke of Gloucester and, later still, King Richard III. Richard’s character has been besmirched as often as it has been defended, and the arguments between his detractors and supporters still rage after several centuries. Was he a ruthless hunchback who butchered his way to the throne, a paragon of virtue who became a victim of Tudor propaganda, or (as seems more likely) something in between?

Some would argue that a true biography is impossible because the letters and other personal documents required for this purpose are simply not available; but David Baldwin has overcome this by an in-depth study of his dealings with his contemporaries. The fundamental question he has answered is ‘what was Richard III really like’.