They were six remarkable women of the Tudor era, six individual and very different women whose lives have passed into legend. We know them as the Six Wives of Henry VIII – and they were not the only women to capture his heart. We always consider them as just that, Henry’s wives, but just what might life have been like being married to one of the most notorious monarchs in English history?

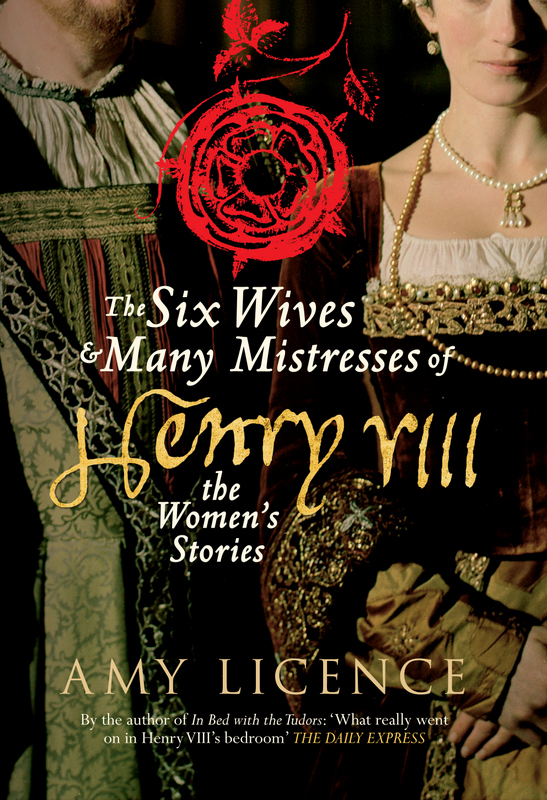

Amy Licence joins us to discuss the women’s perspective in her new book The Six Wives & Many Mistresses of Henry VIII: The Women’s Stories.

We know that Henry put enormous pressure on his wives in terms of fertility, but do you think he sometimes placed unrealistic romantic ideals on his relationships?

When he was in love, yes, he did have unrealistic romantic ideals. However, I think he was really only what we would call romantically “in love” with Catherine of Aragon (at the start), Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard; the others happened to be in the right place at the right time. Henry in love was perhaps more dangerous than a Henry who wasn’t in love; his cruel treatment of Catherine of Aragon and the falls of Anne and Catherine Howard were the result of the depth of his former feeling for them. I don’t doubt he came to love Jane and Catherine Parr, but I think those started more as “comfort” relationships for him. The higher he valued them, the harder they fell.

You examine Henry’s desire for keeping his romantic affairs private – how do you imagine Henry was feeling when Catherine of Aragon made a public show of her displeasure when his affair with Anne Hastings came to light?

I imagine he was absolutely furious that his private business had become public gossip. Catherine crossed an invisible line, in terms of his expectations of her as a wife, and I don’t think he ever forgot it. This argument marked the end of their honeymoon period but it didn’t necessarily mean he was no longer romantically devoted to Catherine. It was a contemporary expectation that upper class men would compartmentalise their wives and mistresses, especially during a wife’s pregnancy and Catherine’s public displeasure threatened to expose the careful self-image he had chosen, of the devoted husband. And for a Tudor King, image was everything. I think this marked a real turning point in their relationship and sparked Henry’s obsession with preserving his privacy.

Can you tell us about the role Henry’s wives had to fulfil as Queen Consorts?

This is an interesting one, as the role of Queen Consort doesn’t appear to have been consistent, but dependent more upon the qualities of the woman concerned. I get the sense that Henry adapted his expectations to what he felt his wife was able to offer, and recognised that he’d been drawn to them for different reasons. So, it is easy to see why he felt able to leave the capable Catherine of Aragon and Catherine Parr as regents in his absence, yet I can’t help wondering whether he would have ever trusted Catherine Howard in such a role. Obviously, there was the public ceremonial role, which they all fulfilled, as well as being the sympathetic and accessible face of royalty; Catherine of Aragon interceded for the apprentices after the May Day riots, Jane Seymour spoke up for those in the Pilgrimage of Grace and even Catherine Howard persuaded Henry to release Thomas Wyatt from his second stint in the Tower. His later wives didn’t really get much of a chance to establish themselves as Queens, not even as figureheads during a coronation, as only the first two were given this opportunity. I also think over time, Henry placed more emphasis on his wives in the private sphere; Catherine and Anne Boleyn had strong public identities but after that, I think he cared less about them fulfilling an ideal of Queenship and more as to whether they would bear a son and prove a suitable wife on a personal level.

Do you think that because Henry truly believed his marriage to Catherine of Aragon to have been invalid in the eyes of God that this placed even more pressure on Anne Boleyn to conceive -and even arguably that Jane Seymour was under the most terrible pressure with two disastrous marriages preceding hers?

I find Henry’s psychology to be opaque on this one; it’s rather a chicken and egg scenario. Did he convince himself that his first marriage was invalid and then look for a replacement, or was it a convenient excuse that he used in order to marry Anne Boleyn? It boils down to the question of Henry’s sincerity. I don’t doubt that he felt it was in his own interests, and the national interest, for him to take a new wife and produce a son. He didn’t appear to have any problem with the validity of his marriage in 1509 but he may well have been convinced by the series of failed pregnancies that his superstitious era would have interpreted as divine disapproval. Whether or not he believed that Catherine and Arthur’s marriage should have prohibited his own, he certainly believed by the late 1520s that they were an invalid couple in terms of his dynastic need. The fact that he decided this almost two decades after his marriage, coupled with the drawn-out process of the divorce really put pressure on his subsequent wives to produce an heir. The need to produce an heir really did shape the marriages of Anne and Jane. There was a precedent established with the removal of Catherine and they had to conceive quickly and bear a healthy son. They knew that was why he’d married them.

You discuss that Henry’s needs in a wife changed as he aged and that this period of his life may have been one of self-deception – evident in his ‘surprise’ meeting with Anne of Cleves. Were his expectations of romance at this stage in his life unrealistic?

Most definitely. We often forget that in his youth, Henry had been one of the most beautiful and attractive men of his day; he was accomplished, learned, a sportsman and conformed to contemporary standards of beauty, plus, he was the King. He must have lit up the room when he walked into it. For years, he was used to being desired for his intrinsic self, his personal attractions but, as he aged, perhaps the greater pull was his status rather than his person. Henry also loved taking part in masques, when he believed his natural beauty and nobility shone through even though his identity was hidden. By the time he had reached his late forties, (he was 48 when he met Anne of Cleves), he was still maintaining this belief, falsely, with the collusion of his court. He had anticipated Anne swooning in his arms, but all she saw was a large, old man who breached protocol to embrace her. It’s surprising that no one warned Anne to expect this, but it was the death knell for their marriage. As King, Henry was absolutely right to expect the performance of romance to continue; it’s ironic that by adopting a disguise on that day though, he actually exposed the truth of his aged appearance and Anne was not impressed.

How difficult do you think it would have been for Henry’s queens to navigate Henry’s sometimes changeable attitudes towards religion and the rival Evangelical and Catholic factions at court?

Paradoxically, I think it could be both easy and difficult. The driving force in Henry’s marriages seems to have been personal; if a wife had borne him many sons and continued to please and flatter him, I suspect he wouldn’t have minded what religion she was, so long as she was discreet. With Anne of Cleves, he was prepared to overlook her religious views because Holbein’s portrait impressed him and it suited him to have an ally against France and the Empire. When he was considering Catherine Parr’s arrest, it was more to do with his annoyance that she had questioned him, which he perceived as disrespect. She was able to talk herself out of it by telling him she had done so to divert him from his pain and learn from him.

I don’t exactly think that Henry manipulated religion to suit his romantic need, there was far more to it than that, and the English Reformation was inevitable, yet his fluctuations suggest it wasn’t his primary consideration and took second place to questions like dynastic need and personal happiness. His attitudes towards religion and the church were not the same, either. If Henry genuinely believed he was God’s representative on earth, (and I believe he did) then the trappings of religion as practised by Rome really were ephemeral to him. He was also susceptible to the persuasion of clever servants such as Cromwell and Gardiner, or the Boleyns, Seymours and Howards, who managed to marry their religion with his other desires. While religion was so central to their lives, I don’t think it was the deal-breaker in his marriages, so long as his wives toed the line otherwise.

While Henry was happy to appoint Catherine Parr regent when he left the country to invade France he almost allowed her to be arrested due to a mere spirited debate in front of others. He was happy to allow Catherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn to become more closely involved in politics than was usually traditional for a consort but would take great offence at complaints of his infidelity. Do you find it strange Henry would entrust his kingdom to his wife yet take issue with what he thought was perhaps disobedience?

No, I don’t find that strange at all. Henry required his Queen to be an extension of himself, to metaphorically be “himself” while he was absent. She had to be an instrument, a conduit of his will, and while he trusted that a wife was able to accept this role unquestioningly, he would have happily left her in charge of the country. From my research, I really do get the sense that everything boils down to Henry’s own ego, his sense of entitlement. But let’s be clear, as a sixteenth century King, he was entitled to his entitlement. Where Henry’s wives ran into difficulties is when they acted independently of him, or contradicted him in any way; where he saw them as challenging his divinely-appointed status. It simply wouldn’t do for anyone to disobey him, and in a wife, he found that the most unforgivable crime, in any of its manifestations. And this was engrained in the Tudor world order, with the husband as the head of the household, commanding obedience and the King as the ultimate authority figure. There’s no question that Henry could be sensitive and once he perceived that Catherine Parr might be challenging his authority by disagreeing with him, it called her whole attitude towards him into question. She was lucky to be tipped off about it. I’m sure she trod more carefully afterwards.

What do you imagine a day in the life as Henry VIII’s wife would have been like?

I’ve got the impression that it could be one of extremes; either sitting quietly reading and sewing with your women in your apartments, listening to music or dancing while Henry was out hunting, or else you were thrust into the middle of his latest whirlwind scheme for entertainments. I’m thinking of Henry bursting into Catherine of Aragon’s rooms late at evening with a band of disguised gentlemen, and the way that the court must have come to life when he and his household were in residence. The Queen was the centre of her own world too, with petitions to hear, activities and visits of her own to fulfil, but she was always orbiting the more dazzling light of the King. She lived in comfort and luxury, as the inventories and ordinances show, but as Henry’s wife, there was always an element of the unexpected, even early on, for Catherine of Aragon, right up to the end, when he planned to arrest Catherine Parr. It must have been an alternation between periods of exhilarance and routine.

We’ve heard a rumour you’re working on an Anne Boleyn biography, can you tell us about it?

I am indeed, but it’s still in the planning stages. I’m researching everything I can to write the most full and detailed account I can of her life, from cradle to grave. I want to explore Anne as a woman ahead of her time; I know that phrase gets used a lot for women of the medieval and Tudor period and mostly, they are in fact, products of their time. Yet I do think there may be a case for Anne, given her learning, her expectations, ambition and desire to have a relationship of romantic equality; I also want to explore her rise to power in the context of gender discourse and the culture that condemned female ambition and ability, using the typical weapons of misogyny. It may be that I look at the evidence and reach different conclusions entirely, but I’ll see where it takes me. I’m due to submit it early in 2016, so it’ll probably be out in the late spring or early summer.

Check out the rest of the stops on Amy’s blog tour this week with a chance to win a copy each day:

Tuesday 21st October Claire Ridgway’s The Anne Boleyn Files presents an excerpt on Mary Boleyn.

Wednesday 22nd October Natalie Grueninger’s On the Tudor Trail presents an excerpt on Anne Boleyn’s early life.

Thursday 23rd October Lara’s Tudor History blog presents an excerpt on Jane Seymour

Friday 24th October Darren’s The Tudor Roses presents an excerpt on Catherine Parr

Saturday 25th October Stephanie interviews Amy over at The Tudor Enthusiast.

Sunday 26th of October Amy wraps the tour up with her final thoughts on her blog His Story Her Story

We have one copy of The Six Wives & Many Mistresses of Henry VIII: The Women’s Stories to give away courtesy of Amberley Publishing. Just leave a comment below by Monday the 27th of October and spread the word!

The Six Wives & Many Mistresses of Henry VIII: The Women’s Stories by Amy Licence, published by Amberley Publishing, 2014.

For a King renowned for his love life, Henry VIII has traditionally been depicted as something of a prude, but the story may have been different for the women who shared his bed. How did they take the leap from courtier to lover, to wife? What was Henry really like as a lover?

Henry’s women were uniquely placed to experience the tension between his chivalric ideals and the lusts of the handsome, tall, athletic king; his first marriage, to Catherine of Aragon, was on one level a fairy-tale romance, but his affairs with Anne Stafford, Elizabeth Carew and Jane Popincourt undermined it early on. Later, his more established mistresses, Bessie Blount and Mary Boleyn, risked their good names by bearing him illegitimate children. Typical of his time, Henry did not see that casual liaisons might threaten his marriage, until he met the one woman who held him at arm’s length. The arrival of Anne Boleyn changed everything. Her seductive eyes helped rewrite history. After their passionate marriage turned sour, the king rapidly remarried to Jane Seymour.

Henry was a man of great appetites, ready to move heaven and earth for a woman he desired; Licence readdresses the experiences of his wives and mistresses in this frank, modern take on the affairs of his heart. What was it really like to be Mrs Henry VIII?

Click here to buy The Six Wives & Many Mistresses of Henry VIII: The Women’s Stories with Free Shipping Worldwide

Amberley’s Book of the Month The Six Wives & Many Mistresses of Henry VIII: The Women’s Stories. Get a 25% discount for online orders. Click here to buy.

Visit Amy Licence at His Story Her Story

Visit Amy Licence at His Story Her Story

Amy Licence on Twitter @PrufrocksPeach

Amy Licence Facebook Fan Page In Bed With the Tudors

Writing about medieval and Tudor history, with a particular interest in women’s lives and experiences. I’m the author of four books and have also written for The Guardian, BBC History website, The New Statesman, The Huffington Post, The English Review and The London Magazine. I appeared in a BBC2 documentary “The Real White Queen and her Rivals” and have been interviewed numerous times live on radio. I’ve also been shortlisted twice for the Asham Award for women’s short fiction.