…that with my soul I love thy daughter and do intend to make her Queen of England.

That Richard III intended to marry his brother’s daughter, Elizabeth of York, is a rumour that we can date back to 1483. It made its way into Tudor-era chronicles, ballads and eventually into Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Richard III. The sinister depictions of Richard’s intentions can be attributed to contemporary attitudes. When the rumours began to spread in Richard’s own court that he was considering marrying his niece, his supporters told him his actions were “to the extreme abhorrence of the Almighty”.

Yet it is far more sinister to depict uncle and niece of having indeed been in love, and worse, having had a sexual relationship. Tudor and Elizabethan writers usually presented Elizabeth as the victim of her uncle’s evil intentions, or lust in some cases. Modern fiction writers, however, are starting to present Elizabeth as the victim of her husband Henry Tudor. Although we can date Henry Tudor’s “dark prince” back to Francis Bacon, he certainly never accused Elizabeth of pining for her dead lover while trapped in a marriage with the man who defeated him and shattered her dreams. The relationship between Elizabeth of York and her uncle King Richard III has long been debated. Was Richard truly intent on marrying his niece?

Westminster Abbey – 1484

After the death of Edward IV in April 1483 and Richard III’s subsequent seizure of King Edward V, Elizabeth Woodville fled with her five daughters to Sanctuary in Westminster Abbey. After the disappearance of her two sons, Edward and Richard of Shrewsbury, her eldest daughter Elizabeth of York was considered by some as the rightful heir to the throne, and was becoming a focus for rebellion. By March of 1484 Westminster Abbey was under siege and Richard was pressuring Elizabeth Woodville to leave Sanctuary. After almost twelve months in sanctuary and probably in fear for her safety, the Queen Dowager struck the best bargain that she could manage, forcing Richard to swear an unprecedented public oath before she would agree to take herself and her daughters out of Sanctuary.

…promise and swear on the word of a king, and upon these holy evangelies [Gospels] of God, by me personally touched, that if the daughters of Dame Elizabeth Grey, late calling herself Queen of England, that is, Elizabeth, Cecily, Anne, Katherine, and Bridget, will come unto me out of the sanctuary of Westminster, and be guided, ruled, and demeaned after me, then I shall see that they shall be in surety of their lives, and also not suffer any manner hurt in their body by any manner [of] person or persons to them, or any of them in their bodies and persons by way of ravishment or defouling contrary to their wills, not them or any of them imprison within the Tower of London or other prison; but that I shall put them in honest places of good name and fame, and them honestly and courteously shall see to be founden and entreated, and to have all things requisite and necessary for their exhibitions [display] and findings [domestic arrangements] as my kinswomen… 1

There has been some speculation that in this bargain, Elizabeth Woodville agreed to a marriage between Elizabeth of York and Richard III. During her time in Sanctuary, Elizabeth Woodville had arranged a bethrothal between Margaret Beaufort’s son Henry Tudor and her daughter Elizabeth of York. They were still considered betrothed when Elizabeth of York was sent to court under her uncle’s guardianship. That Elizabeth Woodville agreed to Richard marrying her daughter is mainly the speculation of modern historians, and some of those eager to slander Elizabeth Woodville by claiming she was greedily trying to restore her own position by placing her daughter on the throne. The late David Baldwin too k a more serious approach to it, but there is no real evidence, and Richard was not actively seeking a new wife at this point. Although Anne Neville’s health was beginning to fail, his son, Edward, was still alive. Sadly he would die only a few weeks later.

Christmas

Later in March Elizabeth of York went to court and joined Queen Anne’s household, where her famed beauty was reportedly attracting a great deal of attention. But at the end of that month tragedy struck, Richard and Anne lost their only son, Edward Prince of Wales. It was a terrible blow to the couple and to their marriage, Amy Licence noting that it was “as if Edward had been a bond that broke them with his death”. 2 Anne’s illness became progressively worse. Polydore Vergil said that Richard was complaining to a number of courtiers that Anne could no longer give him an heir. It is unclear exactly when the rumours about Richard and Elizabeth began, but they were certainly reaching their peak by Christmas of 1484. According to the Croyland Chronicle:

“There may be many other things that are not written in this book and of which it is shameful to speak, but let it not go unsaid that during this Christmas festival, an excessive interest was displayed in singing and dancing and to vain changes of apparel presented to Queen Anne and the Lady Elizabeth, the eldest daughter of the late King, being of similar color and shape: a thing that caused the people to murmur and the nobles and prelates greatly to wonder at, while it was said by many that the King was bent either on the anticipated death of the Queen taking place, or else by means of a divorce, for which he supposed he had quite sufficient grounds, on contracting a marriage with the said Elizabeth. For it appeared that in no other way could his kingly power be established, or the hopes of his rival being put an end to.”3

Why did this cause such a scandal? Strict sumptuary laws restricted the wearing of luxurious materials to the upper ranks of society. Since Richard had declared all of the children of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville illegitimate, to have Elizabeth arrayed in the same manner as the Queen was seen, by some, as shocking. Croyland discusses the anticipated death of Queen Anne, alluding that Richard had discussed divorce prior to Anne becoming seriously ill.

This incident can be, and has been interpreted in several ways. In the eyes of the court, according to Croyland, he was publicly displaying his niece as equal in rank to his Queen. Alison Weir conjectures that Queen Anne would hardly have suggested that Elizabeth appear in similar clothing to her out of kindness, knowing the comment it would cause. “It could only have been King Richard, eager to discountenance Henry Tudor, who ordered that Elizabeth appear dressed as a queen; and in that he showed scant regard for her reputation or for his ailing wife.” 4 According to Vergil, the rumours of their alleged marriage plans reached Henry Tudor in France it “pinched him by the very stomach“.

One could consider Richard was publicly displaying his niece as equal in rank to his Queen. But did Richard really supervise Anne’s wardrobe? It is doubtful. It is more likely that Queen Anne was simply being kind to her niece. Some modern historians even claim that Elizabeth was deliberately trying to outshine the Queen, an act of antipathy from a teenage girl in love with her uncle. We would have to then accept that Elizabeth was in the position to influence what the Queen would wear to an important court occasion, and this is hardly likely.

In fact, all of these scenarios, that Richard forced the Queen to display Elizabeth in this manner, or that Elizabeth was trying to outshine the Queen, are mere misogyny. The most likely scenario is a show of affection and solidarity and the young Elizabeth paying homage to the fashion set by the queen. However if it was the Queen’s intention to display her friendship towards her niece, according to Croyland, it was ill-received.

All th’issue and Children of the Said King been Bastards

Why would Richard III want to marry his brother’s daughter who he had deemed illegitimate? There would have been some obvious immediate advantages for Richard. He had lost both his wife and son in the space of a year, and with a tenuous hold on the throne, an heirless king was vulnerable. Elizabeth was young, beautiful and most importantly, her mother and grandmother had excellent childbearing records. Restoring Elizabeth of York to royal status may have pleased disaffected Yorkists still loyal to the memory of Edward IV and resistant to Richard’s rule because of his treatment of Edward’s sons. Such an alliance and the hope of a prince or princess in the cradle may have afforded Richard a little more time to win people over.

But there was of course two problems. The obvious problem was the blood relation. It is possible the Pope may have issued a dispensation. But Richard could not marry someone of the rank he had imposed on Elizabeth. Even her mother who was considered “common” was of higher rank than Elizabeth at this point, with Richard affording her the title “Dame Grey” from her first marriage. Richard would have had to make Elizabeth of York legally legitimate again, and would then have to acknowledge that her missing brothers were also legitimate, who would then revert to the position of rightful heirs to the throne. A throne Richard had only been able to take after deeming the boys illegitimate.

Loyalte me lye

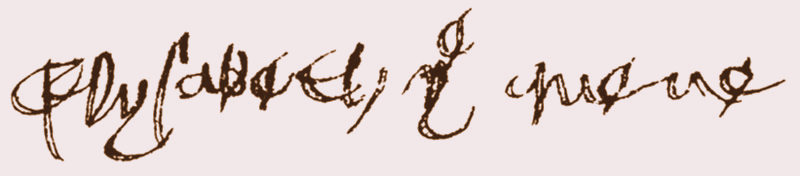

There is no real evidence of either Elizabeth or Richard’s actual feelings for each other. While it is becoming popular for Richard to be depicted as a sort of romantic hero, there is no doubt he was entirely unconcerned with romance when it came to choosing his future bride. Richard was more pragmatic than his brother Edward IV in that department. However it seems uncle and niece were on good terms while she was at court, good enough that he sent her a gift of two books. Both books had belonged to Richard when he was Duke of Gloucester. To give her two of his own books as gifts shows that he must have held her in some esteem. One of the books, Boethius’s Consolatio Philosophiae, bears Richard’s motto “Loyalte me lye”, likely written by Elizabeth and bearing her signature underneath. The other contains the inscription, not necessarily in Richard’s hand, “Iste liber constat Ricardo Duci Gloucestre”. On the same page Elizabeth wrote the motto she had chosen for herself, “sans removyr (without changing), Elyzabeth”. 5

It is certain that she inscribed the books before she became Queen, her signature later read Elysabeth ye Queene and her personal motto “Humble and Reverent“. It is curious that she chose to inscribe the books with his motto. Perhaps Elizabeth was envisioning a future as Richard III’s Queen. Or perhaps it was just another show of solidarity.

Fortune had turned against Elizabeth several times before, she was raised in an environment where one must learn to adapt and survive. It is likely that the idea of the marriage had been discussed, whether rumour or fact. But it is not evidence, as some have speculated, that she was in love with her uncle. In the end Elizabeth would have had little choice in the matter of her marriage, as her guardian, the decision would be made by Richard. As for Richard’s marriage, a King’s marriage was a matter of state.

The Cat and the Rat

Croyland said that “the King’s plan and intention to marry Elizabeth, his close blood relation, was related to some who were opposed to it and, after the council had been summoned, the king was compelled to make his excuses at length, saying that such a thing had never entered his mind. There were some at that council who knew well enough that the contrary was true.” Sir Richard Ratcliffe and Sir William Catesby “whose wills the king scarcely ever dared to oppose” told Richard “to his face, that if he did not deny any such purpose and did not counter it by public declaration…the northerners, in whom he placed the greatest trust, would all rise against him, charging him with the death of the Queen.”6

Ratcliffe and Catesby were said to have brought Richard proof in the form of several priests that the Pope would never sanction the marriage. Avunculate marriage, that is marriage between and uncle and niece or aunt and nephew, was very unusual at the time. King Ferdinand II married his aunt Joanna of Naples but that was not until 1496, more than a decade later and under Pope Alexander VI.

In addition, Croyland claimed that they had brought in “over a dozen Doctors of theology who asserted that the Pope had no power of dispensation over that degree of consanguinity.” This sheds some light on the idea that historical fiction authors enjoy perpetuating, that incest was not “unusual”. Richard was then compelled to publicly deny the charges and “in the great hall at St. John’s in the presence of the mayor and citizens of London and in a clear, loud voice carried out fully the advice to make a denial of this kind.”7

Elizabeth of York was packed up and shipped off to Sheriff Hutton. Sometime after March Richard began negotiating for a marriage alliance with Portugal. It was the negotiations for this marriage that Elizabeth may have been discussing in her now-notorious letter to John Howard, Duke of Norfolk, that has fuelled the wildest rumours of all.

The Buck Letter

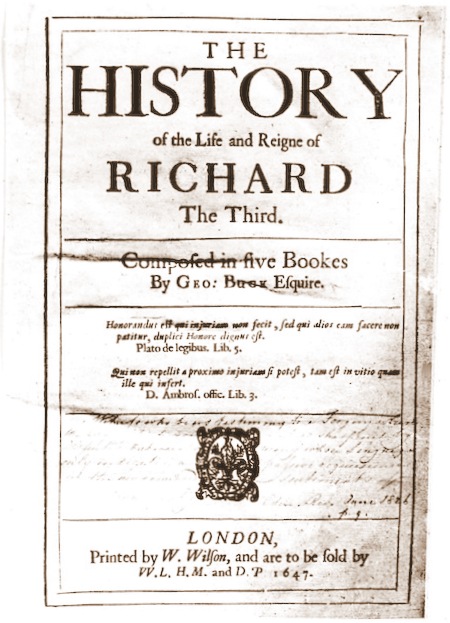

There are two George Bucks. The first George Buck was an antiquarian who served King James I as his master of Revels. Buck’s most important work, his History of the Life and Reign of Richard II was not published until after his death. Buck happened upon the previously undiscovered Croyland Chronicle, containing Richard III’s suppressed act of Parliament, Titulus Regius, which had declared Edward IV’s children illegitimate. Although Henry VII had ordered all copies of it destroyed, the chronicler had copied the text and Buck was able to reproduce it. Buck’s work was largely based on the original manuscript of the Chronicle and is an extremely important early history.

But one of Buck’s discoveries that historians have spent the last few decades arguing over, is the letter from Elizabeth of York to the Duke of Norfolk.

Historians have long debated the authenticity of the letter and of Buck’s credentials. But historian A.N. Kincaid, who edited a new edition of Buck’s Richard III in 1979, believed Buck’s sources were reliable. Unfortunately the original letter from Elizabeth of York is lost. Buck claims to have seen it in the private collection of the Earl of Arundel and reproduced the text. Buck’s original manuscript has survived, complete with notes and revisions from his great-nephew, also George Buck. But it was damaged by fire in the 18th century and parts of the text are missing or illegible.

This is what remains of the original text of George Buck’s manuscript:

“…st she thanked him for his many Curtesies and friendly

…as before…

in the cause of…

and then she prayed him to be a mediator for her to the K…

ge who (as she wrote) was her onely joy and maker in…

Worlde, and that she was his…harte, in thoughts, in…and in all, and then she intimated that the better halfe of Ffe…was paste, and that she feared the Queene would neu.…”

The second George Buck (Junior) took his great-uncle’s manuscript, revised it heavily and it published it as his own. This is a copy of the letter from the edition available online:

“When the midst and last of February was past, the Lady Elizabeth, being more impatient and jealous of the success anyone knew or conceived, writes a letter to the Duke of Norfolk, intimating first that he was the man in whom she affied, in respect of that love her father had ever bore him, etc. Then she congratulates his many courtesies and friendly offices, in continuance of which she desires him, as before, to be a mediator for her to the King in the behalf of the marriage propounded between them; who, as she wrote, was her only joy and maker in the world; and that she was his in heart and thought, withal insinuating that the better part of February was past, and that she feared the Queen would never die.”8

This text is reproduced from the manuscript held in the British Library (Egerton 2216):

But when the midst, and last of ffebruary was past, the Lady Elizabeth (beinge more impatient and suspitious of ye successe, then every one knewe, or conceived ) wrote a letter to the Duke of Norffe: Intimateinge first therein, that hee was the man, in whome shee most affyed, and that she had reason soe to doe, knowinge the King her fathr much loved hym, and that hee had been a very faith=full servant vnto hym, and to the Kinge his brother, then raigninge, and serviceable to all king Edwa: Children; then shee congratu=lates, his many courtesyes, and friend=ly offices, in continuance of which, shee desires hym, to bee a mediator to [hym]\the king/ for her, in the behalfe of the marriage propounded betweene them, whoe (as shee wrote) was her onely ioye, and maker in this world, and that shee was his \in/ hart, in, thought, in body, and in all; insinua=tinge, that the best part of ffebr: was past, and that shee feared the Queene would never dye;”9

This text is from A.N. Kincaid’s 1976 edition of Buck’s History:

[[]But when the mid]st and more days of February were gone, [the Lady Eli]zabeth, being very desirous to be married, and growing not only impatient of delays, but also suspicious of the [success,] wrote a letter to Sir John Howard, Duke of Norfolk, intimating first therein that [he was the] one in whom she most [affied,] because she knew the king her father much lov[ed him,] and that he was a very faithful servant unto him and to [the king his brother then reign]ing, and very loving and serviceable to King Edward’s children.

First she thanked him for his many courtesies and friendly [offices, an]d then she prayed him as before to be a mediator for her in the cause of [the marriage] to the k[i]ng, who, as she wrote, was her only joy and maker in [this] world, and that she was his in heart and in thoughts, in [body,] and in all. And then she intimated that the better half of Fe[bruary] was past, and that she feared the queen would nev[er die.]”10

The word “body” has been seen as suggestive and having sexual connotations by some writers. Alison Weir told us “I don’t take that view nowadays. But when I was researching that book, A.N. Kincaid’s new translation (or rather, reconstruction) of the controversial letter on which that theory rests had not long been published, and for the first time historians could read how Elizabeth declared that she was the King’s in heart, in thought, in body and in all. The words ‘in body’ had never appeared in previous versions of the letter, so it looked as if they had been censored. I was not the only historian to interpret them as referring to a sexual relationship. But on reflection I think they mean something else entirely.” 11

The letter is no proof that Elizabeth of York was longing to marry her uncle. Had the letter even been referring to any marriage, and this remains unclear, it may have been referring to a marriage Richard was arranging for Elizabeth of York, and not necessarily to Richard.

Portuguese Interlude

Proposed plans for a double-marriage alliance with Portugal were only discovered in the 1980s. Sometime after March of 1485 Richard had entered into negotiations to marry the Infanta Joanna, the sister of John II of Portugal, and his cousin the Duke of Beja to marry an unnamed ‘daughter of Edward IV’. On the 22nd of March 1485 Sir Edward Brampton went on an embassy to Portugal, but we have no record of the marriage negotiations being entered into on this first visit. The negotiations may have commenced after this first visit.

Another point to consider is that the later negotiations never mentioned Elizabeth of York by name. Sir Edward Wydeville mentioned the proposed marriage alliance between the Duke of Beja and one of Edward’s daughters after Elizabeth of York was already married to Henry Tudor. Edward mentioned the possibility of a marriage Elizabeth’s younger sister Cecily. How serious this was is unclear, Edward was on a social visit on his way back to England, and not an embassy.

Moreover there is no evidence that Richard himself was particularly attached to the idea. Joanna was an infinitely unsuitable choice for a bride, she was 33 and had spent much of her life in a convent. Joanna had never given birth, meaning there was less guarantee of a much-needed heir. Sending Elizabeth of York abroad might not have been the best political move. Elizabeth could have been the possible focus for rebellion. Richard would have been far better off keeping her close by and marrying her off to one of his own loyal men.

The Portuguese marriage negotiations commenced well after the rumours that Richard wanted to marry his niece were brewing. They are not proof that he never intended to marry his niece. The best defence is common sense.

To gratify an incestuous passion…

While we have seen several entirely imaginary depictions of romantic love between uncle and niece in fiction recently, the one thing we can almost positively rule out is sexual intercourse. Elizabeth had left sanctuary in March of 1484 and was at court soon after. Had they been sleeping together it is almost certain that Elizabeth would have conceived, for she conceived on either the first or one of the first few occasions she slept with her husband Henry Tudor. Prince Arthur was born eight months after the wedding, either he was premature, or Henry and Elizabeth decided to start trying to conceive just before the wedding.

Of course it cannot be ruled out that either Elizabeth was using contraception, or that Richard’s fertility can be questioned – it had been many years since he fathered a child – but this is leading into fairly ridiculous territory. There are no mentions of Richard being unfaithful to his wife Anne. It is extremely unlikely Richard III would risk his somewhat tenuous position and his own reputation to have extra-marital sex with his own niece, or that he would have risked ruining her reputation.

Elizabeth’s reputation was spotless, when she eventually became Queen. Vergil says Richard “had kept her unharmed with a view to marriage.” Catesby and Ratcliffe accused Richard of wanting to “gratify an incestuous passion for his niece”.12 The word gratify clearly indicates that there was no rumour at the time that Richard had done so.

Dynastic marriages were made with alliances and advantages in mind, not with love or sexual attraction. Had Richard seriously considered marrying his niece, he would have been considering that she was a focus of rebellion for disaffected Yorkists, that by marrying her he may win their loyalty and keep the threat of rebellion at bay. If he had indeed considered it at all, and the likeliest scenario is that it was simply a rumour. Richard had lost his son and his wife, and needed an heir. He was in the market for a wife, not a romance. As for Elizabeth’s feelings on the matter, they are ultimately irrelevant. Elizabeth of York was in no position to do anything other than what she was told.

All of these speculations are, of course, rather distasteful. They are a product of the lines between historical narrative and fiction becoming increasingly blurred, and historians continually having to disprove fictional stories about historical figures. It is not only Richard who has suffered at the hands of historians and authors here. Elizabeth of York has been blamed by some writers for giving fuel to the rumours, speculating that she was in love with her uncle, a ludicrously misogynistic take on the matter. It is typical in medieval history to clutch at fragments of facts, for fragments are all we have most of the time. But unlike novelists, historians should arrive at conclusions, not because the idea is the most entertaining, but what is the most likely; decided with the benefits of hindsight, by historical precedents, by the facts available and with common sense. And common sense dictates this was merely a rumour designed to injure Richard III, and perhaps even Henry VII.

- Okerlund, Arlene Elizabeth of York Palgrave Macmillan 2011, pg 33/34 ↩

- Licence, Amy Anne Neville: Richard III’s Tragic Queen, Amberley Publishing 2013, pg 522 (iBooks version) ↩

- Pronay, Nicholas; Cox, John; The Croyland Chronicle Continuations 1459-1486 Richard III and Yorkist History Trust, 1986 p. 175 ↩

- Weir, Alison Elizabeth of York: The First Tudor Queen, Jonathan Cape 2013, pg 122 ↩

- Weir, Alison Elizabeth of York: The First Tudor Queen, Jonathan Cape 2013, pg 138 ↩

- Pronay, Nicholas; Cox, John; The Croyland Chronicle Continuations 1459-1486 Richard III and Yorkist History Trust, 1986 p. 175 ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Buck, George, The History of the Life and Reign of King Richard III ↩

- Supplied by A.N. Kincaid, from B.L. MS. Egerton 2216 ff. 266V-267, Bodleian MS Malone 1 ff. 272v-273 and Fisher (Fisher Rare Books Room, U. of Toronto Library), ff. 273-273v ↩

- Supplied by A.N. Kincaid ↩

- The words in body were omitted in a print version, despite appearing in manuscript copies, see above ↩

- Ingulph version of the Croyland Chronicles ↩

- Updated: 17/03/2015, 29/12/2020 ↩