One of the common approaches to creating the ‘villainous’ Jane Boleyn is to seperate her from her Boleyn family, to reinforce the image that she was an outsider. This has been done in many ways, and one particularly popular argument claims that because Jane’s father, Lord Morley, was a supporter of Princess Mary, this meant that Jane was naturally at odds with the Boleyn family. However, there’s no definite evidence that the Parkers had met Mary prior to Anne and George Boleyn’s executions. The first recorded meeting was June 4th 1536. Therefore, a ‘long’ association prior to this meeting is unlikely. Thus, the premise that Jane attended a demonstration in support of Princess Mary in defiance of her Boleyn family has a distinct lack of credible evidence. It is generally thought that the demonstration took place in October of 1535, at Greenwich, about a year after Jane was banished from court by Henry VIII. I have always maintained that Jane being banished from court for quarrelling with one of Henry’s mistresses on behalf of her sister-in-law, Anne Boleyn, actually shows she was a loyal family member. There has been commentary that this incident shows Jane’s ‘talent for plotting’, which I think simply demonstrates that one of Jane’s greatest enemies will always be misogyny.

When it comes to historical record, the record of Jane’s banishment dated October 13th, 1534, comes from the Imperial Ambassador Eustace Chapuys, a reliable source, even if he was hostile towards the Boleyns.

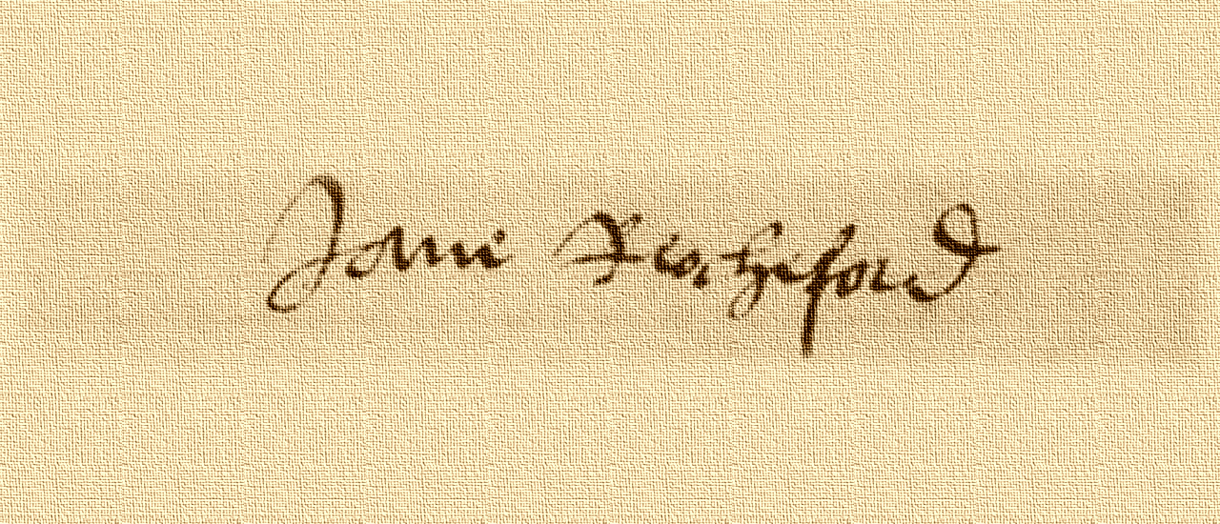

Of late days lord Rochford’s wife has been banished the Court because she had conspired with the[…]Concubine to procure the withdrawal from Court of the young lady whom this king has been accustomed to serve[…]whose influence increases daily, while that of the Concubine diminishes.1

and

The wife of Mr. de Rochefort has lately been exiled from Court, owing to her having joined in a conspiracy to devise the means of sending away, through quarrelling (fasherie) or otherwise, the young lady to whom the King is now attached. As the credit of this latter is on the increase, and that of the King’s mistress on the wane, she is visibly losing part of her pride and vainglory.2

The mysterious woman that Jane quarrelled with was reported to have sent Princess Mary a message ‘to tell her to be of good cheer, and that her troubles would sooner come to an end than she supposed, and that when the opportunity occurred she would show herself her true and devoted servant.’3 Her identity has never been discovered. It seems that, rather than dutifully or obediently, Jane entered into the fray enthusiastically. This incident demonstrates Jane’s allegiance to her sister Anne, as she would have called her, when it was public opinion that Anne’s influence with Henry was waning. As a result of Jane’s interference, she was banished from court by Henry, quite a harsh punishment.

It is difficult to gauge exactly when Jane was welcomed back to court. There was a further mention of Jane’s banishment on December 19th 1534, in which Chapuys reiterated that Jane had been banished, as if it had been questioned, ‘It is true that Rochford’s wife was sent from Court for the reason that I have heretofore written’. Chapuys seemed to despair of the king forming a lasting attachment to his latest mistress, however, because of Henry’s ‘changeableness’.4 So at this late stage of the year, according to Chapuys, Jane was still in exile, and the mistress was still about, but Henry was tiring of her. Jane put a good deal of effort into her New Year’s Gift for Henry in 1534, sending a shirt with a collar of silver work embroidery.5 It is most likely, with Henry’s mistress slipping back into obscurity, that Jane was back at court early in 1535.

So it is rather strange that some historians have made the stretch that Jane, having suffered the humiliation of banishment, would risk it again by leaving Anne’s side to go and participate in a demonstration in support of Princess Mary in April of 1535. It should be noted that this theory is not universally supported by Tudor historians. In two major popular works, David Starkey barely mentions Jane at all in his Six Wives, and called the suggestion ‘thin and ambiguous’ in another publication.6 Antonia Fraser also didn’t mention it at all in her Six Wives. It’s not often mentioned in newer Tudor books, clearly influenced by Julia Fox’s 2005 biography of Jane which debunked many such myths. It was, however, championed by Eric Ives, in his seminal biography of Anne Boleyn, that is incredibly hostile to Jane. It claims that Jane was ‘otherwise known as Anne’s enemy’7 and that Jane’s alleged attendance at this demonstration shows that she ‘did not share her husband George’s commitment to Anne’s cause.’8 Ive’s source for the alleged demonstration is Paul Friedmann’s 19th century biography of Anne, and Friedmann’s primary source, a letter from Jean de Dinteville, preserved in the Letters and Papers of Henry VIII archive. The letter claims that:

a great troop of citizens’ wives and others, unknown to their husbands, presented themselves before her, weeping and crying that she was Princess, notwithstanding all that had been done.9

Friedmann added:

On the margin of that part of the report in which this circumstance is recorded we find the words (written by Dinteville himself) : “Note, my Lord Rochford and my Lord William.” The ambassador clearly meant that Lady Rochford, Anne’s sister-in- law, and Lady William Howard were among those who had cheered Mary.10

However, it’s not clear at all. Surely if Lady Rochford and Lady Howard had been arrested then the French ambassador would have written their names in the report, and not their husband’s. Friedmann’s conclusion is a considerable stretch, and the same sentiments have been repeated by Ives, with the added hint of animosity between Jane and Anne. Ives has a clear interest in presenting Jane as an ‘enemy’ of Anne, because he later claims that Jane did indeed give evidence against Anne and George, quoting non-contemporary sources,11 speculating that Jane was jealous of George and Anne’s closeness, or that her family’s association with Princess Mary influenced her. He even wrote that ‘we may, if we choose, smell malice’ in regards to Jane sending a message to George when he imprisoned in the Tower, and that her interests were later looked after by Cromwell, insinuating it was a ‘reward’.12 The agenda is painfully clear here.

Returning to Dinteville’s letter, it has been mislabelled as being from ‘The Bishop of Tarbes to the Bailly of Troyes’ and dated October 1535. The error is noted in Letters and Papers with footnote that ‘A translation of this letter is printed by Mr. Froude in his Appendix to “the Pilgrim” (p. 100) as a letter from Dinteville to M. de Tarbes, and dated in Oct. 1534.’ 13 As The Pilgrim: A Dialogue on the Life and Actions of King Henry the Eighth was edited by William Thomas, Clerk of the Council to Edward VI, however, it is a possibility that the letter was indeed from 1534.

Friedmann uses the date of April 1535, and writes that ‘a great many women, in spite of their husbands, had flocked to see [Princess Mary] pass, and had cheered her, calling out that, notwithstanding all laws to the contrary, she was still their princess.’14 William Thomas’s translation, however, tells us they ‘walked before her at their husbands’ desire’.15 Furthermore, the translation in the Letters and Papers archive states ‘unknown to their husbands’. Both letters also mention the King had a new love interest, the archived letters, that he had ‘new amour’, and Thomas’s that he had a ‘new fancy’.

The fact that Jane was banished for interfering with the King’s ‘new fancy’ suggests the demonstration for Mary may have taken place in October 1534, as dated by Thomas, when Jane was banished for conspiring with Anne against Henry’s new mistress. Of course, some will suspect that a banished Jane attend the protest out of spite. However, this is neither reasonable and realistic. The first obstacle here would obviously be Chapuys. Two reports within two months on Jane would absolutely not have failed to mention that she was arrested for attending a demonstration supporting Princess Mary. It beggars belief to suggest he would leave out an arrest of a Boleyn family member protesting on behalf of his beloved Princess Mary. The second obstacle is that the correctly dated letter claims the ladies supported Mary ‘at their husband’s desire’, a thing that George Boleyn could not have desired. The theory itself is a stretch, as we have discussed, and Jane herself is not mentioned in the original document. We don’t even have corroborating translations or dates. Dinteville’s account cannot be used as a source for anything other than a demonstration may, have taken place in support of Princess Mary, and, it really is questionable if such an event even happened. Going by the complete lack of contemporary evidence, it is quite clear Jane was not in attendance.

- British History Online, ‘Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 7, 1534’, British History Online Vol VII #1257. ↩

- British History Online, ‘Calendar of State Papers, Spain, Volume 5 Part 1, 1534-1535,’ British History Online, October 1534, 1-15 p. 267-282 #97 ↩

- L&P Vol 7 #1257. ↩

- L&P Vol 7 19 Dec #1554. ↩

- E. Ives, The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn, Second Edition, (Oxford: Blackwell, 2004) 216. ↩

- M. Axton, J. P. Carley (ed) Triumphs of English: Henry Parker, Lord Morley, Translator to the Tudor Court, New Essays in Interpretation (London: British Library, 2000) 14. ↩

- Ives, Anne Boleyn, 194. ↩

- Ives, Anne Boleyn, 293. ↩

- L&P Vol 9 #566. ↩

- P. Friedmann, Anne Boleyn; a chapter of English history. 1527-1536 Vol II (London: McMillin & Co, 1884) 128. ↩

- Ives cited Bishop Gilbert Burnett here, who was writing in 1679. While admitting Burnet was not contemporary, he speculated that Burnet may have had access to source no longer extant, which is very doubtful. ↩

- Ives, Anne Boleyn, 332. ↩

- L&P Vol 9 #566. ↩

- Friedmann, Anne Boleyn, 128. ↩

- W. Thomas, The Pilgrim: A Dialogue on the Life and Actions of King Henry the Eighth J.A Froude ed., (London : Parker, son, and Bourn, 1861.) 101. ↩