Dr Leigh Straw joins us to discuss the other side of underworld crime and her new book, Sophia Lane.

You specialise in Australian history and crime history, can you tell us what particular aspects of crime history you enjoy researching?

I really enjoy researching female criminality in Australia from the nineteenth century into the first decades of the twentieth century. My most recent non-fiction work, Drunks, Pests and Harlots, investigated the lives of women charged with offences against good order such as drunkenness, prostitution, vagrancy, and being an idle and disorderly person. In the early twentieth century in Australia, such offences were regarded as a serious threat to the social order and women faced up to six months in prison for committing these crimes. I am most interested in understanding the ways in which criminal women have been depicted in the press, courts and by the authorities at the time.

My interest in exploring issues around women and crime led me to research more closely the lives of Tilly Devine and Kate Leigh. Not only are they notorious female underworld figures, but also they are unique in Australian history for being women running criminal syndicates. For this, they are intriguing to historians looking to emphasise the importance of accounting for female experiences of crime, rather than the general focus on male criminality.

In my work at university – informed by my research – I enjoy researching and lecturing on topics relating to criminal underworlds in Australia, Britain and the United States from 1800 to the present. Some main areas of study include prostitution, prohibition, baby farming, and infanticide. We also investigate the rise of organised crime and transnational organised crime in the modern world.

What was the inspiration behind Sophia Lane?

I read Ruth Park’s The Harp in the South as a teenager and fell in love with the story and the historic backdrop of Surry Hills and the surrounding areas. Park’s story, along with the years I lived in Darlinghurst and Surry Hills, inspired me in my writing of Sophia Lane. I have also been fascinated by criminal underworld figure Kate Leigh for some time and wanted to write a story featuring her and also inspired by her rendering in Larry Writer’s Razor.

What made you decide to tell the story from Linney’s point of view, a fictional figure in a historical backdrop?

I decided to tell the story from Linney’s point of view as it gave me the opportunity to develop different characters and historical personalities within her. She is a composite of a number of women who worked in the police force in the early days, along with bringing together different females who have influenced me through the years. Linney is both the strengths and weaknesses of influential women I have met along life’s journey.

You have also included a modern character, Abby. Why did you want to tell Abby’s story alongside Linney’s?

I wanted to tell Abby’s story alongside Linney’s as it shows the connection women can have across generations and how empowering it can be. As an historian, I am drawn to the stories older women share about their experiences and both the remarkable and ordinary things they have seen in their lifetime. I wanted Abby to be a modern character drawn back into the past and engaging with the history that surrounds us in the present, but which we often take for granted. Linney’s story allowed Abby to think about the lives that shaped her local community and both closeness and distance of the past.

I found the story of the Women’s Police force especially interesting, can you tell us a little more about the beginnings of it?

Women were introduced into the police force in Australia in an effort to better deal with what were termed ‘wayward’ girls and women in the early twentieth century. In the first decades of the twentieth century, Australian society was still governed by Victorian attitudes towards female respectability. The so-called ‘good’ Australian woman was expected to thrive in her domestic life as a wife and mother. Women were seen as the upholders of welfare and domesticity. When a woman deviated from this ideal, she was depicted as having suffered a ‘fall’ from femininity. The Women’s Police was introduced to better deal with such deviant women and keep wayward females out of sight and reform their ways. First established in 1915 in New South Wales and closely followed in the other Australian states, the Women’s Police were expected to assist in managing and controlling female public lives and ensure a respectable female ideal was upheld in society. Female officers were expected to prevent young women from entering into prostitution, make sure drunken women were escorted home or into care, and look after young girls loitering about the streets.

Despite the importance of their work in monitoring female lives on the streets, women were not an accepted part of the police for many years. Paid less and not offered overtime, for example, they suffered a double standard in their work conditions. They often faced open hostility from male officers. However, it is testament to the work of the first female officers – women like Lillian Armfield – that the police force across the country gradually came to accept women as an equal part of the force and embrace greater equality.

How was prostitution affecting women and society in the 1920’s?

Prostitution – labelled the ‘great social evil’ – became a part of Australian society from the first days of the penal settlement in Sydney from 1788. Through the nineteenth century, it prospered in the cities and port towns and within and around the main gold mining areas. By the late nineteenth century, with the growth of urban centres like Sydney and Melbourne, the public nature of prostitution featured in political and media discussions. In an effort to regulate and contain prostitution, the local authorities in the Australian cities introduced a campaign to take sex off the streets and confine it to the brothels. The thinking behind this was that prostitution could be contained and taken out of the view of the public. In doing so, the sanctity of marriage could be upheld. In this sense, local councils, the police, and state governments wanted to enforce respectability on the streets. However, while the brothels prospered, there remained a high demand for street prostitution and women often supplemented brothel work with street work. During the First World War, debates raged around Australia about the serious threat prostitution was said to pose to society as a health issue. Prostitutes were forced to undergo regular health checks and ensure personal hygiene as best they could. While it went a long way to better regulating both men and women’s health, street prostitutes felt they were harshly treated by a society unable to accept their work.

The regulation and containment of prostitution played right into the hands of women like Tilly Devine and Kate Leigh. From the late nineteenth century, men could be charged with living off the proceeds of prostitution. It was more likely that women would be arrested and charged with soliciting for sex than living off its proceeds. The loophole initially allowed Devine and Leigh to set up a number of brothels and avoid lengthy sentences. However, their entry into the drug trade had long-lasting impacts for the connection between prostitution and drugs. Caught in a cycle of sex and drugs, prostitutes entered into a downward spiral working for Devine and Leigh in Darlinghurst and Surry Hills. In the histories of prostitution in the 1920s we can see the origins of a connection between drugs and sex in criminal underworlds and what eventuated into organised crime.

Do you think that we don’t hear enough of the women’s side of the story in regards to our underworld history?

Given the general crime statistic that three in four criminals are men, the common assumption in both popular interest and scholarly work has been to focus on male criminality. However, since the 1970s and particularly in the last decade or so, the topic of women and crime has come to dominate historical and criminological studies. In fact, the uncommon involvement of women in crime is most fascinating. Why is it that women engage in crime? Are their crimes different to men? Such questions fascinate historians and other researchers and offer insights into another aspect of women’s history all too often overlooked.

In Australian history, despite an exaggerated fascination with Ned Kelly and modern criminals like Chopper Read and the Melbourne underworld killings from the 1990s, the women’s side of the story has progressively started to gain prominence in what we know about underworld history. Key female writers and historians such as Lucy Frost and Kay Daniels have done much to include female voices and experiences in what we know of convict history. Larry Writer’s work on Kate Leigh and Tilly Devine went a long way to re-writing Australian criminal history to include prominent women involved in the underworlds of Sydney in the first decades of the twentieth century. However, in terms of what we know about women and crime in general in Australia, there is indeed more work that needs to be done to extend what we know about female experiences and the role women play as both victims and perpetrators in everyday crimes as well as the more sensational cases that feature in the media.

I think we hear something of the stories women can tell in relation to crime in Australia but we need to extend it further.

What do you hope readers will learn from Linney’s story?

I want readers to understand from Linney’s story some of the experiences of the first women who worked in the police force in Sydney and, on the other sides of the law, the prostitutes who worked the streets of Darlinghurst and Surry Hills.

Linney’s story was a hard one to write as it made me confront both the strengths and weaknesses of the female psyche and the many ways in which some women struggle to be accepted and the devastation they feel when they fail to meet the high standards they set for themselves. I want readers to be drawn to the vulnerabilities of Linney and relate to her.

Linney’s story is a love story but it is a tragedy. Her pride prevents her from being able to see that love has the ability to overcome devastating circumstances. All too often we make decisions for the people we love based on what we think they want or expect. Linney’s failing is that she thinks she knows what Max wants.

There is incredible strength in Linney’s story, too. She tried to protect the man she loved and carried the secret of what happened to her for most of her life. Only Max and Kate Leigh knew the truth. In revealing her story to Abby, Linney was finally able to release the pain she had carried for so long. In doing so, she brought Abby back into the world – at a time when she felt isolated and lonely – and reminded her of the gift of true love.

In the end, I really hope readers will see the value in second chances. The message in Sophia Lane is a hopeful one. We all deserve a second chance. And if you truly love someone, you will give them a second chance.

Leigh is currently researching the life of notorious Sydney underworld figure, Kate Leigh. Leigh recently won an award for her criminal women history book called ‘Drunks, Pests and Harlots‘. Her other books include Wisdom in Words: Robert Kennedy’s Search for Meaning, A Semblance of Scotland: Scottish Identity in Colonial Western Australia and the historical fiction title Legacy.

Visit her website at leighstraw.com

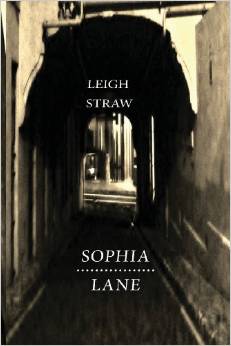

Sophia Lane by Leigh Straw, published by Spartan Publishing 2013

Eastern Sydney in the 1920s. Slumland streets controlled by crime bosses Kate Leigh and Tilly Devine. Lyndsey Collier, an ambitious country girl, joins the Women’s Police. As her work draws her into Sydney’s underworld, Lyndsey discovers a greater threat than the criminals she is investigating. Betrayed by a corrupt police officer, Lyndsey escapes into the shadows of underworld Sydney to protect the man she loves. A lifetime away and nearing death, Lyndsey reveals her story to Abigail Hollingsworth, a nurse at Kirkland Home for the Elderly. Caught up in the tale, Abby must also confront her own troubled marriage. Sophia Lane is a haunting story of loss and regret and a love that brings together two women generations apart.