Her great-nephew Peter Scales joins us to discuss Lillie’s legacy and her “special piece of war work”.

Can you tell us about how you came to read your great-aunt Lillie’s diaries and what you knew of her before you read them?

A few years ago I had passed on to me my Great Uncle George’s diaries ( which he kept from his early teens until his death aged 87) along with a mass of family papers. In late 2012 I came across Lillie’s war diaries amongst the boxes of papers and read them for the first time.

I regret that I was too young to know Lillie before the 1939 war and my family moved to Devon while Lillie and George remained up in London. My sister, who is 4 years my senior stayed with them at times after the war and remembers them as a devoted couple and Lillie as a very kind person. So my knowledge of her is from reading George’s diaries, some of her letters and my impressions of her in her war diaries. She certainly had a good sense of humour.

What made you want to publish Lillie’s diaries?

As soon as I began to read her diaries I realised that they were a pretty unique record as the bulk of what is published is about the Fighting Fronts and a minimal amount about the Home Front. They also covered such an interesting range of subjects of life at home, bringing out the changes in social attitudes, the expanding role of women together with the experiences of the ANZACs and also the technological advances- from horses being requisitioned at the start of the war to the prospect of passenger air flight at the end. The majority of UK soldiers on leave said nothing about their ordeals but the men staying with Lillie and George had no such inhibitions, as they looked on Lillie as their “English Mother” they found it very easy to confide in her.

Therefore, bearing in mind 2014 is the war’s centenary, I thought they were worthy of publication- and so, luckily, did Amberley!

The diaries really paint a vivid picture of English patriotism during the war, I was rather struck by Lillie’s resolve to do her own part for the war effort. We can have rather different ideas about war now, how did you feel when you were reading the early entries in her diary?

The first thing that struck me was that the man in the street had no inkling that war was imminent. Also the country was ill prepared for war- in 1914 our regular army and reserve was 392,000 and the German was 3,800,000 ! We were completely reliant on volunteers both for war service and domestically. This was another striking feature her diary highlights right from the start.

Lillie writes extensively of the food rationing and how the rationing affected the whole country, from her observations on ‘stout people’ becoming thin to the farmers not producing butter because it was too expensive. She mentioned being ill on and off and losing quite a bit of weight but did not go into much detail, do you think her own strict rationing may have affected her health but she was determined to still do her part?

According to George’s diary Lillie was advised by her doctor in December 1913 to cut down on her commitments as she was lacking in energy – this was due to thyroid problems. She obviously tried to get involved with the war effort right from the start but it proved too much for her but things seemed to have improved by the Autumn of 1916. I have the impression that the local shops were supportive of her household because they were giving a roof to the ANZACs and other Colonials.

Even though Lillie was of the upper-middle class she seemed perfectly happy to budget and go without new clothing, I was surprised to see her write that one new dress would do her for a couple of years. She seemed to adapt easily to restricting the normal luxuries she was used to didn’t she?

I think she was imbued with a strong sense of Christian duty and patriotism therefore it was only right in her mind to conform to rationing, stop entertaining, cut out holidays for example- at least she had her furs to wear if coal was in short supply!

Lillie was quite convinced the war was affecting people’s mental health, particularly that of her father and her mother who died during the war. But she also wrote that “depression affects the morale of the nation”. Do you think this shows her determination to stay strong for the sake of others?

Bearing in mind that the majority of the soldiers they housed were sick and exhausted let alone wounded she must have felt that she had to be strong for their sakes. Her empathy for them comes through so strongly. Some of them were mere boys and time and again she comments on how she “felt” for the men.

Lillie calls taking soldiers into their home “our special piece of war work”, and concludes her entries when the last of “our Colonials” have sailed home. How important was Lillie to these men and their morale?

Answering this would be pure conjecture on my part. However , life at Elm Bank would have given them a complete escape from the horrors they faced back in the trenches. Her presence would have given them a haven of domestic reality and the hospitality afforded to them must have helped to heal their mental wounds. This had a lasting affect for she and George were still corresponding with them in the late 1940’s and were getting food parcels to ease the constraints of rationing which the UK was still burdened with. Check up on James Brunton Gibb of Sydney whose profile mentions his friendship with George and his “English Mother- ” on the Library of NSW web site.

While in England James Brunton Gibb became a close friend of Mr and Mrs George Mc. A. Scales. They corresponded with each other, Lillie Scales signing herself “your English Mother”. Her letters are preserved from 1920 to 1923. In 1921 the English couple visited James in Sydney. James Brunton Gibb further papers, 1873-ca. 1990 Library of NSW

What do you think is unique about your great-aunt Lillie and her observations?

I do not think Lillie was unique of her class in trying to help the war effort by Home Front activities. However, she was unique in what she recorded, the wealth of material she had access to and the “special piece of war work” which was not completed until all her Colonials who had survived were safely returned home.

Peter Scales writes about his family background and their connection to Australia:

My Great Grandfather, George Johnston Scales went to Sydney at the age of 26 with his 2 younger brothers John and William and set up in business as Scales Bros, Lace Merchants and General Importers. George returned to England in 1857 and in 1860 the partnership was wound up. He then became a partner in the City of London firm of Australian Merchants, eventually named McDonald Scales & Co. His brother John set up in business in New Zealand.

GJS had 6 sons, the eldest George McArthur and the youngest Harold became partners in the family firm. Hugo emigrated to Sydney in 1897 and was accountant for W & A McArthur at Macquarie Place and Charles emigrated to Adelaide in 1898 and became partner in Crookes & Brooker Ironmongers and Importers.

George -aged 27- married Maria Elizabeth Thomas- Lillie aged 22 in 1890. Both families were Wesleyan Methodists and George and Lillie were staunch supporters of their local Chapel, he as organist, choir master and both ran the Sunday Schools and Bible reading classes. They were also very involved with Missionary work.They had no children.

On being made partner in 1887 George was sent to Australia for a year to meet the firm’s clients. He and Lillie went out again in 1904 on a year’s business tour of both Australia and New Zealand and also stayed with the families of Charles and Hugo.

Lillie’s eldest brother Arthur went out to Adelaide in 1906 and was enthroned as Bishop to the Diocese. You can see from this the strength of the links that existed. I have more relatives now in Australia than in the UK!

A list of Lillie’s “Colonials”, ANZACs that stayed with Lillie and George Scales during the war:

Serg. Dallas Taylor, New Zealand

Reginald, Jack and Cecil Dunn, Adelaide, South Australia

Guy, Will and George Wagg, Masterton, New Zealand

Ernest, Alban and Gainor Jackson, Auckland, New Zealand

Frank Brown, Te Kopura, New Zealand

Silas Wright, New Brunswick, Canada

G. S. H. McKay, Canterbury, New Zealand

Walter Bradley, Sydney, New South Wales

Amess B. Coleman, Sydney, New South Wales

Bay and Rod Piper, Adelaide, South Australia

Harry Brooker and Betty Brooker, Adelaide, South Australia

Arthur Brooker, Adelaide, South Australia

Bert Chesters, Ipswich, Queensland

Jim Gibb, Sydney, New South Wales

Murray Sinclair, Sydney, New South Wales

Marland Nield, Sydney, New South Wales

Alexander McCrae, Perth, Western Australia

A. C. Stephens, Dunedin, New Zealand

Clarence Lane, Totara North, New Zealand

A. J. Kendall Baker, Adelaide, South Australia

H. Rupert Brown, Fullarton, South Australia

Alan E. Black, Sydney, New South Wales

Ridley Reid, Alberton, South Australia

D. G. Moore, Claremont, South Australia

Eric Marshall, Adelaide, New South Wales

With thanks to Amberley Publishing.

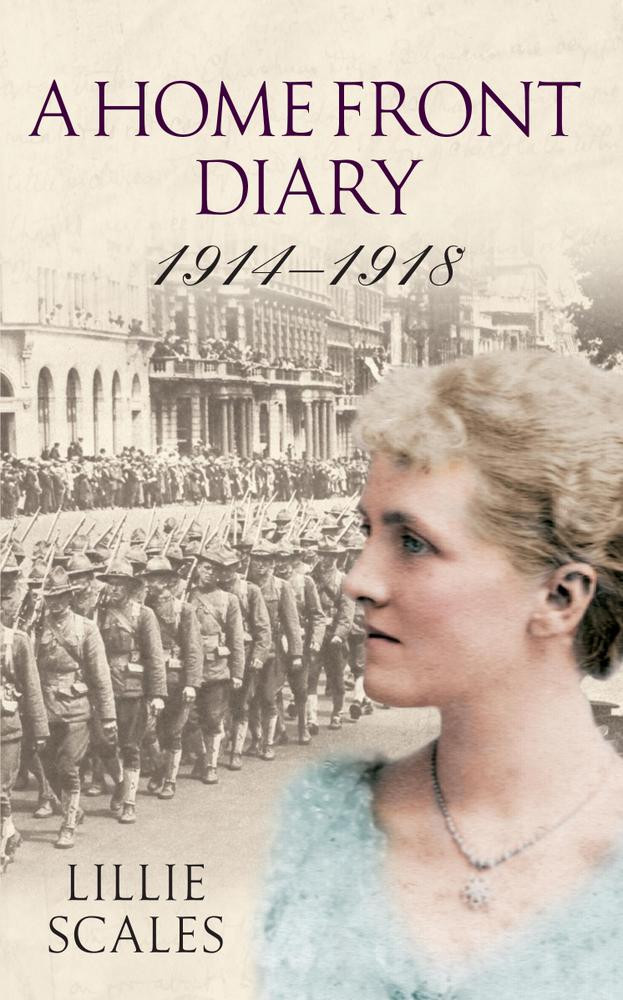

A Home Front Diary, Edited by Peter Scales, published by Amberley Publishing 2014

On Tuesday 28th July 1914 Lillie Scales heard that war was imminent. Four years of turmoil ensued, and from her home in North London, Lillie recorded it all in the pages of her diary.

By 7th August she had turned up for first-aid classes along with a thousand other women. Men had rushed to enlist. By October Lillie and her husband George had offered to take in Belgian refugees, and later in the war they gave a home to many ANZACs while they were on leave. As a result, Lillie’s diary also holds accounts of daring escape and of Front Line action. Through her diary we hear of Zeppelin raids, rationing, the sinking of the Lusitania, the shelling of Scarborough, and the loss of dear friends. Lillie’s detailed diaries provide insight and lend immediacy to this fascinating subject.

Lillie Scales was aged forty-six at the outbreak of war and was living with her husband in Hornsey Lane, North London; both were lifelong diary keepers. As they had no children, they felt it their duty to house Belgian refugees, and their family and business connections with Australia led to them opening their home to ANZACs as well as other colonial troops.

Lillie Scales’ great-nephew Peter Scales lives in Faringdon, Oxford. His Grandfather, William Johnston, was the second of the six sons and a London solicitor. Peter’s father George Courtney Johnston, was William’s only child born in 1900 and was a partner in the family firm up until the 2nd World War.

Peter was born in November 1934, named (for his sins) William Peter Johnston, became a Chartered Accountant and married Angela in 1962. The couple have two daughters, Kate and Emma. He did not join the family firm.