The following is spoiler-free but references themes from the His Dark Materials book trilogy.

The Golden Compass has its twelve year anniversary coming up shortly. I first saw it on its Boxing Day release in Australia in 2007. My excitement had been building for months and months. It had a wonderful cast, design and score. But while I was initially spellbound by the visuals, I felt a growing sense of flatness throughout the film. I still had hope and a little dread at what I thought was to come, but the abrupt ending left me confused. The actual ending of the first book in the His Dark Materials trilogy, Northern Lights, was supposedly bumped to the film’s sequel. The sequel was never made. I accepted the film’s final scene with some resignation. Newline had been marketing the film as a great children’s adventure for months on end, and I should have known that is something that the film simply could not accomplish with that ending. Writer and director Chris Weitz, who was a huge fan of the books, lost control of post-production at some point and large amounts of footage were censored. The result was a thin, strained and self-conscious story. The Golden Compass has something to hide.

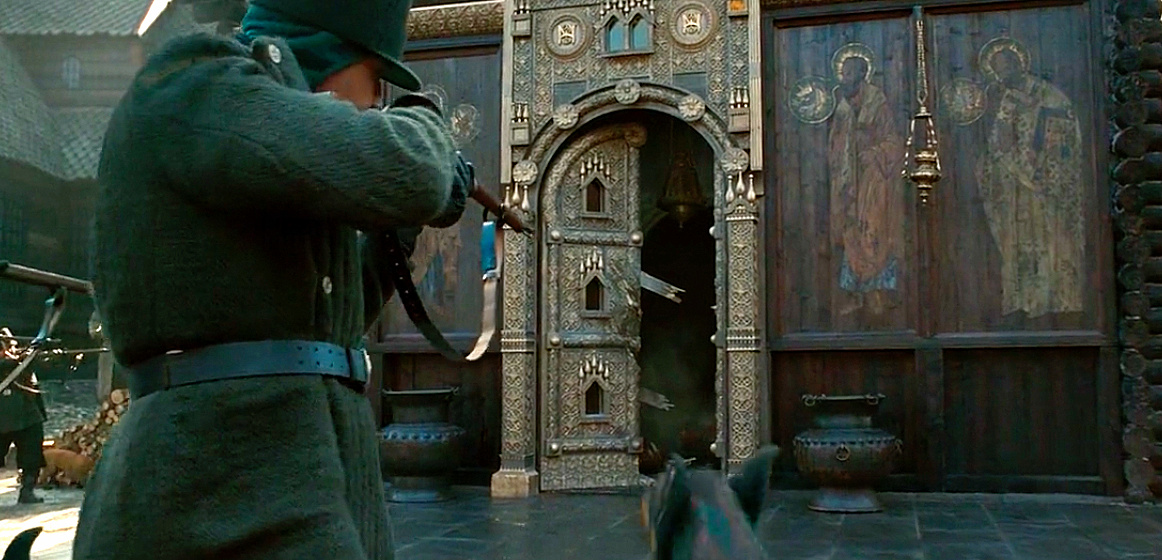

Despite my disappointment I am still very fond of The Golden Compass. But I had not seen it in full for many years before I decided to finally watch it again last night. I was curious about the fan’s passionate attachments to the actors who portrayed beloved characters from the books despite the almost-universal panning of the film, attachments which have caused inevitable reactions over casting choices for the upcoming BBC television adaptation His Dark Materials. The film was pleasant enough, there was nothing overtly offensive or any deliberate betrayals of the book. The Magisterium still looked like a religious organisation. And despite the censoring producers still left a clearly visible Christian reference in Trollesund, where Iorek Byrnison first appears. Interestingly one of the frames shows a powerful image of Iorek railing against his oppressors flanked by Byzantine iconography.

A fresh watch has left me wondering why we have become so attached to certain portrayals of characters. Sam Elliot has long been my vision of Lee Scoresby, he looks and sounds perfect for Lee and I was very nervous about the new casting. It turns out that casting someone younger and the complete opposite of Sam Elliot did the trick. I am looking forward to Lin Manuel Miranda’s take on Lee. But there were no other adult characters I was particularly attached to. Because of the strained quality that pervades The Golden Compass everything remains a fraction too understated. Nicole Kidman was so wonderful Philip Pullman has made Mrs. Coulter a blonde in her earlier years, but she never managed to show the full depravity of the character. Claims that she had no time to do so with the material from the first book conveniently forget Bolvangar. Daniel Craig wasn’t in the film for long enough to leave a lasting impression. Equally, Eva Green, who I unashamedly adore, had little time to do much with Serafina Pekkala. From this viewing my favourite performance besides Mrs. Coulter, who has dominant screen time, is Jim Carter’s charismatic Lord Faa. Perhaps we have grown so attached to certain portrayals because it is all we have. This is not to diminish the wonderful performances from the actors or poor Chris Weitz’s original intentions for the film. Philip Pullman even said he hoped there would be a director’s cut one day. Or perhaps my fondness for the old film is due to the fact it was made with love, even if the studio butchered it in post-production.

I was, of course, thrilled along with all of the other fans when I heard that BBC and Bad Wolf were making a television adaptation, something Pullman himself has been suggesting for years. But besides watching the trailers, I had, for the most part, avoided most of the news surrounding the show up until last week.

After the opening scene of episode one was revealed, what I felt was a real spoiler, I decided I may as well read some early reviews and recent interviews. So far a couple of American reviews, clearly not book readers, have reflected a typical Hollywood distaste for subtlety, which is to be expected, and a couple of British reviews attempting to attribute contemporary relevance, also to be expected. At the premiere screenwriter Jack Thorne made a strange comparison between Lyra and current celebrity child activist Greta Thunberg, which simply does not work, although Thorne later attempted to clarify on his Twitter account that they were both “filled with goodness”. He also claims that he thought Asriel’s story was the obvious one to be told and that he admired Pullman for telling Lyra’s, something he has mentioned more than once. But as Pullman himself once told a fan “I told the story to find out what happened after Lyra got trapped in the Retiring Room and overheard things she wasn’t supposed to.” Asriel is certainly an enigmatic character, but in the end he is merely the masculine of Lyra with failings. Asriel is an enigmatic, beguiling renegade like our Lyra, but also another adult capable of betrayal. It leads me to wonder if producers don’t want to underutilise James McAvoy and are expanding on Asriel’s actual role. Or perhaps it’s just to remind fans the protagonist is female, but this is hardly an exciting development in British television.

I was far less thrilled when I heard HBO was coming on board. While it is obvious the series needs the funding it does not need American production values and the anxieties that go with them. So far there has already been an odd decision to change the sex of Mrs. Coulter’s dæmon because of the “male genitalia issue”, which shouldn’t really be an issue, because very few people would look for it, and dæmons are not true animals, therefore distinguishable from them. And in an interview with producer Jane Tranter released this weekend it was claimed that Lyra was sixteen years of age in The Amber Spyglass, and not twelve as Lyra herself just reminded us in The Secret Commonwealth. I am speculating here, but the American version of The Amber Spyglass bowdlerised the scene in which twelve year-old Lyra first experiences sexual attraction, removing several sentences from the paragraph describing sensations she was feeling. It is not clear if Tranter or the interviewer have described Lyra as sixteen in this article and it may be an error, but considering that Dafne Keen is already fourteen, it may be the case that they are ageing Lyra’s character for practical reasons, with a potential two seasons to complete. It could also be that producers are aware that a lot of the book’s characters go through ordeals at a tender age. It puts me in mind of a reader questioning George R.R. Martin at an appearance I attended several years ago about why young characters like Arya were subjected to so much. The man was outraged. Outraged. In answer George mentioned historical figures like Harry Hotspur and Joan of Arc but the questioner was not mollified. Some viewers may actually be disturbed by many of the things Lyra and other children her age have to endure. His Dark Materials was created over twenty years ago and concepts of children reaching adulthood are disparate in even Western countries. I could be ruminating over an error but it seems likely that they are planning on ageing the characters and as such, will be at significant odds with Pullman’s concept of grace, that is, losing the artlessness of childhood and coming of age.

Tranter has also denied that the series is an attack on religion, saying, rather expansively, that “”Philip Pullman in these books is not attacking belief, is not attacking faith. He’s not attacking religion or the church, per se. He’s attacking a particular form of control, where there is a very deliberate attempt to withhold information, keep people in the dark, and not allow ideas and thinking to be free. … It doesn’t equate to any particular church or form of religion in in our world. So we should be clear on that.”

Now His Dark Materials doesn’t need to be about religion. Philip Pullman himself welcomes you to his website with the statement that “As a passionate believer in the democracy of reading, I don’t think it’s the task of the author of a book to tell the reader what it means.” In an artist this is a mark of supreme confidence. Prior to the release of The Golden Compass Pullman made equally confident remarks such as “My books are about killing God”, although to place this in context he was comparing the subversiveness of his text to that of Harry Potter which attracted allegations of “promoting witchcraft”. Can the series shake the atheist stigma? Pullman has more recently described himself as agnostic, something that should be clear from overarching concepts of His Dark Materials. It is also clear that, for the author, the Magisterium represents the church as an institution, wherever that may be, its ability to be corrupted and the problems of combining church and state. None of this is shocking in a country that remains deeply affected by centuries of religious upheaval. The books and The Golden Compass have drawn the ire of the Vatican itself. It doesn’t seem possible to separate the intention from the story. But children are cleverer than most adults allow. The themes may shock deeply religious adults to the core but young viewers will be far more occupied with Lyra’s journey to save a friend.