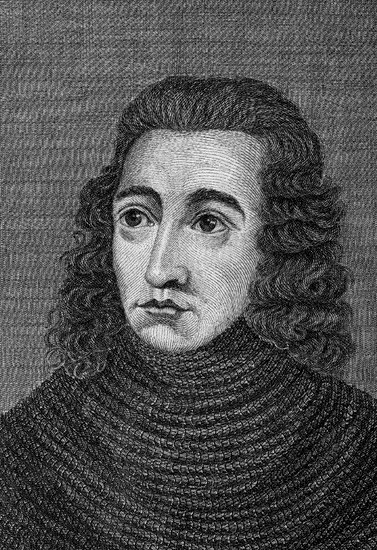

We know him as false fleeting perjured Clarence, always as a traitor, sometimes as a drunk and a madman. We certainly remember his brothers. Edward IV may have been a notorious womaniser, taken the throne of England over the corpses of thousands and murdered his predecessor, the virtually helpless King Henry VI. But we remember him for his glistening court, a romantic hero who married for love and a brilliant military general. King Richard III may have been maligned by history but he has the benefit of his own historical society. Conveniently some of Edward IV’s crimes have been attributed to Richard, but his devoted band of Ricardians and many historians have brought the real Richard III to light. But what of George? He is lost in time. Even his remains have vanished.

We know him as false fleeting perjured Clarence, always as a traitor, sometimes as a drunk and a madman. We certainly remember his brothers. Edward IV may have been a notorious womaniser, taken the throne of England over the corpses of thousands and murdered his predecessor, the virtually helpless King Henry VI. But we remember him for his glistening court, a romantic hero who married for love and a brilliant military general. King Richard III may have been maligned by history but he has the benefit of his own historical society. Conveniently some of Edward IV’s crimes have been attributed to Richard, but his devoted band of Ricardians and many historians have brought the real Richard III to light. But what of George? He is lost in time. Even his remains have vanished.

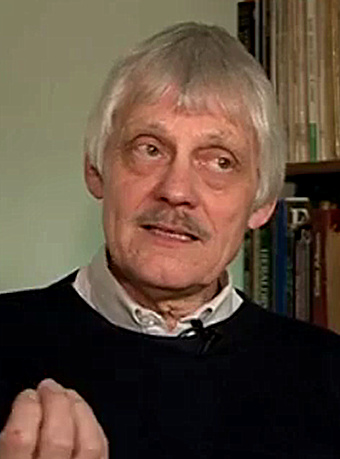

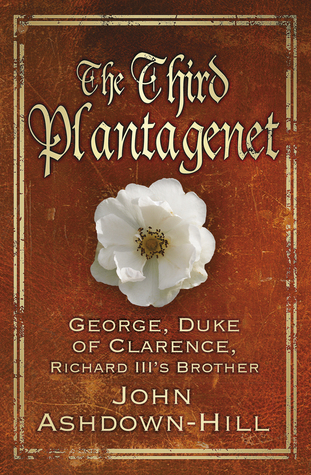

Dr. John Ashdown-Hill’s new book The Third Plantagenet gives us a fresh look at George, at his childhood, his formative years, his fall from grace and his afterlife. It breathes new life into the shadowy figure of George Duke of Clarence, presenting a complex and believable portrait of a man who deserves his own place in history.

Dr. John Ashdown-Hill joins us today to discuss the forgotten York brother, George Duke of Clarence.

You present a rather more complex portrait of George Plantagenet than we are used to seeing, what compelled you to research his life?

I suppose my fundamental approach to historical research is based on trying to get to grips with issues to which previous generations of historians seem just to have given simplistic and repetitive answers. That was why I researched Eleanor Talbot and her relationship with Edward IV, and that was why I researched The Last Days of Richard III – trying hard to get behind all the legends about the last six months of Richard’s life. It’s also why I’m now researching the complex story of ‘The Dublin King’ (usually know to history as ‘Lambert Simnel’).

Just like Eleanor Talbot, the Duke of Clarence was an obvious example of a significant late fifteenth-century figure about whom we knew very little. But I personally was drawn to George, partly as a result of my DNA research, and partly as a result of a kind of family link.

How do you think George was affected by the events of 1460-1461?

I think given his age, and his apparent relationships with his parents and younger siblings, it must have been a very traumatic time for him. His father and other relatives were suddenly killed and subjected to post mortem insults, while George himself was in such potential danger that his mother had no option but to send him off to a strange land, accompanied only by his younger brother and some servants. There, at first, he was just an unwelcome refugee.

But then, ironically, for George, the final outcome was that he not only survived that traumatic experience, but that he then suddenly found himself to be the second highest ranking person in England. That might have given him the dangerous illusion that he was invulnerable and could do whatever he wanted!

What may George’s first meeting with his older brother Edward IV have been like?

We know that George met Edward on one occasion in his early childhood, but otherwise the two brothers probably saw very little of each other while George was growing up. Their ages and lifestyles separated them. So I suspect that when George finally found himself forced to accept Edward as ‘the boss’, he rather resented it.

Do you think George may have felt the need to be independent from rather early on?

As I say in the book, his childhood experiences probably made him see himself in one sense as ‘the king of the castle’. The only person who outranked him, in the little private world in which he grew up, was his father. So the death of his father – and the experiences which followed that – probably encouraged him to assert himself.

Do you think some of George’s resentment towards the Woodvilles came from the fact that his brother’s first heir would replace him?

I think that (like many other members of his family) George resented the Woodvilles first and foremost as social upstarts. But for him there was one particularly significant and personal effect of Edward’s relationship with Elizabeth Woodville. At the time when that marriage was publicly announced, George was the heir to the throne. But obviously if Elizabeth Woodville then produced children, they would outrank George and push him down from his high rank. I think George liked to see himself – and to be seen – as important, so he was bound to resent anyone who might cause him to be demoted.

Why do you think George formed an alliance with the Earl of Warwick?

Why does it need an explanation? Surely it was a perfectly natural thing. Warwick the Kingmaker was a close relative, whom George had probably been brought up to see as an important supporter of the York family.

But when the Woodville marriage was publicly acknowledged by Edward IV, HE (the king) must have seemed to both George and Warwick to be undermining things.

In other words I think that George’s alliance with Warwick was in no way surprising. It was simply what one might have expected. I’m sure that during the five years from 1464 to 1469 Warwick and George would have felt that THEY were maintaining the true Yorkist position. The oddity – the change which does need some explaining – is the gulf which developed between Edward IV and Warwick over the marriage issue – a development which made Edward seem to George and Warwick to be the betrayer of their family cause.

I was interested to learn that Jasper Tudor – uncle of the future Henry VII – spent a year with George in 1470-71. Can you tell us a little more about this?

It’s intriguing, because Jasper ‘Tudor’ was later the advisor of his nephew, Henry VII. Neither Henry nor Jasper ever met Richard III, as far as we know. But Jasper did get some opportunity, during the Readeption, to get to know George. So I think it’s interesting that some aspects of the later ‘Tudor’ mythology about Richard III sound more like descriptions of George than descriptions of the real Richard. For example there is no doubt that George was ambitious, self-assertive and sometimes insensitive, whereas Richard shows no signs of those characteristics.

Do you think, given George’s fictional afterlife, we’ve become a little complacent about why Edward IV brought about his brother’s death?

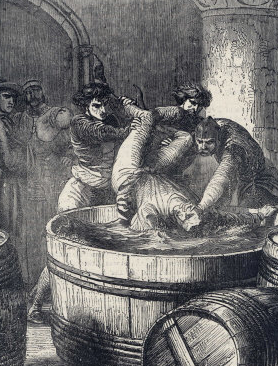

There’s certainly a myth that George was a drunkard – a story for which absolutely no shred of evidence exists. I presume this is simply based on the story of his execution. It implies that perhaps people in the past were dubious about whether George was really executed by being drowned in a wine barrel, and were trying to find a logical reason for that story.

Earlier historical accounts of George’s attainder and execution stress a link with the case of Ankarette Twynyho, so readers may be surprised to discover what I have to say about that! I hope they will also be intrigued by my revelation regarding the background of Thomas Burdet. Incidentally I think that Burdet – or his Oxford University necromancers – may have been behind the ‘Prophecy of G’ which Shakespeare and other ‘Tudor’ writers later had such fun with.

What on your thoughts on the manner of George’s execution?

I suppose I had always been a bit sceptical about the traditional reports of the manner of his death. But when I actually examined the evidence, I found that several independent late C15th accounts report the same information. Indeed, one of them produced a bit more detail about what had taken place. At the same time I found some interesting evidence which suggested to me that maybe kings preferred not to SPILL the royal blood of their close relatives. In the end readers must form their own conclusions about how George was put to death, but I’ve presented all the evidence I could come up with.

Did your work on the search for the remains of Richard III inspire you to research the mystery behind the Duke and Duchess of Clarence’s missing remains?

In some ways things worked the other way round.

First, when I was trying to produce a mtDNA sequence in 2003 for my colleagues in Belgium (so that they could test the possible remains found there, which they thought might be Margaret of York), I considered all the possible sources – including locks of Edward IV’s hair and also, of course, the Tewkesbury bones. But at that time the published results of an examination of the Tewkesbury remains, carried out in the 1980s, seemed to suggest that the those bones couldn’t possibly be the remains of the Duke and Duchess of Clarence. So at that period I wrote them off.

But when I published the mtDNA sequence for Richard III and his siblings, which I got from Joy Ibsen (the living relative I tracked down), Tewkesbury Abbey contacted me and asked if they could use my DNA evidence to test the bones in their Clarence vault. At that time I suggested waiting a while. But in February 2013, when the living DNA sequence I had published was found to match that of the Leicester bones, the abbey came back to me and asked again for my help. So in April 2013 I went and spent several days down in the Clarence vault, examining all the archaeological evidence there, while a colleague re-examined the bones – with some very interesting results!

What evidence do we have of George’s appearance?

There is a contemporary account which seems hitherto to have been completely ignored or overlooked, but which suggests something very interesting about George’s physique. If true, this evidence might explain some aspects of George’s character, as well. Intriguingly, the same piece of evidence also impinges on my current research regarding the true identity of ‘the Dublin King’!

As for George’s facial appearance, I have sought out all the images of him I could find – including two C15th images, which were hitherto unknown or ignored. My conclusions suggest how George fits into the wider context of the York family, and which of his relatives he resembled, and to what extent. Also the surviving portraits of him (like the surviving portraits of Edward IV and Richard III) seem to give a consistent picture of his hair type.

What gave you the idea of having some of George’s descendants contribute their thoughts on him?

Following the discovery of the remains of Richard III, some institutions and organisations have been very scathing about the idea of Richard’s family having living descendants. Some people call them ‘distant relatives’ and say they have no rights in respect of their ancestors. Well, I totally disagree with that. Without the help of the living Ibsen family descendants, I would never have been able to publish Richard III’s mtDNA sequence – which enabled us to establish the identity of the bones found in Leicester. What is more, in the course of that research I got to know Joy Ibsen as a person – she wasn’t merely a source of genetic material!

As a result of my genealogical / DNA research on the house of York, I also had contact from lots of other Plantagenet descendants. So when I was writing The Third Plantagenet it seemed obvious to me that I should involve George’s descendants in the book about their ancestor (if they wished to be involved – and some of them did). George’s living descendants are actually numerous, and the wonderful thing is that one line of them has managed to achieve two things which George himself longed for, but failed to get!

You said that some of your fifteenth-century Dorset ancestors appear to have been in George’s service, what idea of George did you have growing up?

As a teenager, I just had the traditional picture of George – derived, in my case, largely from Shakespeare’s Richard III. Nevertheless, I was always intrigued by him. Later, when I was having some of my own ancestral tombs restored in Dorset, I came across unknown and unpublished images of George and Isabel in a Dorset church. That made me realise that actually there might still be ways of finding out more about him than it had previously been assumed we could ever know. There might be more unpublished and hidden evidence out there, that I could find, if I looked.

Can you tell us a little about your next book?

I’ve described my latest project, The Dublin King (The History Press January 2015) as a sequel to The Third Plantagenet. It was the work on George which first led me on to the story of his son, Edward, the Earl of Warwick – and then on to the connections between that and the story of ‘Lambert Simnel’. At the same time some of the evidence I discovered when researching The Third Plantagenet has also proved to be very important in interpreting aspects of the story of The Dublin King.

With thanks to The History Press.

Dr. John Ashdown Hill

Dr. John Ashdown Hill

I am a freelance historian; historical researcher; writer and lecturer. I am a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, and a member of the Society of Genealogists, the Richard III Society,the Centre Europeen d’Etudes Bourguignonnes, and have recently been elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London

My doctoral research was centred upon the client network of John Howard Duke of Norfolk in North Essex and South Suffolk. Since 1997 I have regularly given historical talks, and published historical research, achieving a certain reputation in aspects of late medieval history. I was the leader of genealogical research and historical adviser on the ‘Looking for Richard‘ project, which led to the rediscovery of the remains of Richard III in August 2012. My Richard III work demonstrates, I believe, that I have a special interest in controversial topics, and a talent for taking a fresh approach, which can sometimes lead to significant new discoveries.

I have currently had five history books and numerous historical research articles published. My sixth book – The Third Plantagenet, a study of George, Duke of Clarence, is due out in March 2014. Due out in 2015 is The Dublin King, the true story of Edward, Earl of Warwick, Lambert Simnel and the Princes in the Tower. My latest book Royal Marriage Secrets recently received an excellent review in The Spectator. As a result of my work on the Richard III project I participated in British, Continental and Canadian TV documentaries on the search for Richard III. Subsequently I have also participated in a general historical documentary on the life of Richard III for the USA, and interest has been expressed in the possibility of further TV work based on two of my books.

You can visit me at johnashdownhill.com

Visit the Looking for Richard website.

Buy The Third Plantagenet: George, Duke of Clarence, Richard III’s Brother by John Ashdown-Hill, published by The History Press 2014

Buy The Third Plantagenet: George, Duke of Clarence, Richard III’s Brother by John Ashdown-Hill, published by The History Press 2014

Less well-known than his brothers, Edward IV and Richard III, little has been written about George, Duke of Clarence and we are faced with a series of questions. Where was he born? What was he really like? Was it his unpredictable behaviour that set him against his brother Edward IV? George played a central role in the Wars of the Roses played out by his brothers. But was he for York or Lancaster? Who was really responsible for his execution? Is the story of his drowning in a barrel of wine really true? And was ‘false, fleeting, perjur’d Clarence’ in some ways the role model behind the sixteenth-century defamation of Richard III? Finally, where was he buried and what became of his body? Can the DNA used recently to test the remains of his younger brother, Richard III, also reveal the truth about the supposed ‘Clarence bones’ in Tewkesbury? John Ashdown Hill exposes the myths surrounding this pivotal and central Plantagenet, with remarkable results.