In 1483 twelve year-old King Edward V and his brother, nine year-old Richard Duke of York were taken into the Tower of London to await Edward’s coronation. Yet the next King of England to be crowned was not Edward V. Richard III deposed his nephews and took the throne. After a rebellion broke out the boys were taken further into the Tower and after the summer of 1483 they disappeared altogether. This is where the sources go silent. Their fate has been the centre of relentless debate and speculation for five centuries.

The Princes in the Tower: Did Richard III Murder His Nephews, Edward V & Richard of York? is a long-overdue examination of the various theories surrounding the boys’ disappearance. It tackles each suspect, John Howard, Duke of Norfolk, Henry VII, Sir James Tyrell and the Duke of Buckingham. It separates the facts from the fiction, analysing the contemporary sources, rumours and the impact of medieval literature. Moreover this book challenges us where we have become complacent, as Dr. Wilkinson tells us “The question, therefore, should not be ‘Who killed the Princes in the Tower?’, but ‘What happened to the Princes after they disappeared?”

Dr. Josephine Wilkinson joins us to discuss the one of the greatest historical mysteries of all time, the disappearance of the Princes in the Tower.

Typically books written on the subject of the disappearance of the “Princes in the Tower” focus on a single suspect. Your book examines several historical figures who have at some point been implicated in the disappearance of the boys, why did you want to analyse the various arguments rather than focus on one subject?

As I explain in the introduction to my book, The Princes in the Tower is a collection of essays which I had written as stand-alone pieces over a period of several years. My aim, as I approached each essay, was to address a particular theory regarding the disappearance of the Princes; some of these theories focus upon a person, others a text. To concentrate on one subject would be to ignore many of these theories, which I felt deserved an airing and which continue to pop up from time to time; it would also have placed unnecessary limits to the question my book attempts to address.

You mentioned that Richard III himself would have known the futility of thinking that by proclaiming his nephews illegitimate would mean that they no longer posed a threat to him. While we can only speculate, why do you think Richard III made no move to proclaim the death of his nephews, especially as he could have easily used the Duke of Buckingham as a scapegoat after his execution?

As you know, the corpses of dead mediaeval monarchs were traditionally exposed to public view. This was done primarily so that people could see that the king was really dead, thereby precluding any attempt by supporters to ‘produce’ him at a later stage – in other words, to avoid as far as possible the emergence of pretenders or to discredit those that did come forward. With the Princes still alive, there were no corpses to display, so that option was closed to Richard.

Buckingham could have made a good scapegoat but for the fact that there were those living who knew he’d had nothing to do with the disappearance of the Princes and might have taken it upon themselves to say so. It would have been incredibly risky of Richard to proclaim the boys dead. He had no way of knowing what might have been going on behind the scenes – someone could have produced the Princes at some point, or one or both of them could have appeared, having perhaps decided to win back the throne. Even though they were deposed, Richard was still responsible for their safety. The best and safest strategy lay in anonymity, and that meant keeping silent about what had happened to them.

You said that the fact that so many people were ready to accept that Perkin Warbeck was the Duke of York shows that the rumour that the Princes had actually been murdered was far from widespread. Do you think later fictional representations of Richard have done more to shape the belief that he was responsible for their murder?

Although the belief that Richard had murdered his nephews was not as widespread as is often believed, it is important to note that Richard was held, by some, to have been responsible for their deaths in his own lifetime. Without giving too much away, I noted in my essay ‘The Rumour’, that stories to that effect began to circulate among those connected with the autumn rebellions (of the ‘Buckingham rebellion’, if you prefer). As I traced the chronology and the trajectory of the rumour, I was able to reveal the probable source for the calumny against Richard. Contemporary sources make for powerful testimony, which is why they must be treated within context and subject to critical analysis. Modern belief in Richard’s culpability stems from these sources, many of which have also informed fictional representation of Richard.

Modern historians tend not to view Thomas More’s “History of Richard III” as an actual history, and you called it a “study in morality”. Considering More abandoned the book and it was published posthumously, why do you think earlier historians were prepared to accept this as a true account of the life of Richard III?

Indeed, it is a study in morality and so much more. Earlier historians did not apply the techniques used on sources by historians today. In other words, they tended to take texts at face value, accepting them without asking questions of them. In addition to this, Thomas More was – and still is – known as a great scholar, a superior intellect and a man of integrity. For these reasons, when the title of History was applied to More’s work, it was accepted without question that he had written a genuine historical study of Richard rather than an allegorical piece.

What do you think of the remains that were found in 1674 under the staircase leading to the White Tower? Although it is coincidental that Thomas More did say the boys were buried “at the stayre foote” he also said that they were later moved and buried in a secret place. There have been many arguments about these remains belonging to the Princes considering the depth (10 ft) they were found at. What is your opinion on the remains that now rest in Westminster?

Yes, Thomas More said that the remains of the Princes were moved because Richard was not happy with the original burial place. Some scholars overlook this, or else invent reasons why More might have been economical with the truth about that particular aspect of his narrative. Of course, this presupposes that people still consider his work to be history, when it is not.

That the remains were found at such a great depth need not preclude their burial during the mediaeval period. Over the centuries, land levels rise, so that what was ground level in Richard’s time is now several feet underground. If you recall, they had to dig over five feet down to reach Richard’s bones, and he lay in land that had remained largely untouched since the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The Tower, by contrast, had been subject to building works throughout its history, which brought shifts in land levels.

The only way to be really sure of whether or not the bones in Westminster Abbey belong to the Princes is through DNA analysis – but then, that would only confirm that they are the remains of the Princes, not that they were murdered or by whom.

You said that death was the expected fate of a deposed king. Do you think this is the main reason we tend to accept that the Princes were actually murdered in the Tower?

Possibly, but the main reason, I think, is the compelling evidence put forward in contemporary sources that Richard was responsible for his nephews’ deaths. In fact (although I did not have space to write this) it is not necessarily true that all deposed kings were killed by their successor. There is good evidence that Edward II survived his reign – see Ian Mortimer’s analysis in his excellent book Medieval Intrigue for example.

Your book Richard III the Young King to Be, will be followed by another biography of Richard. Can you tell us a little more about what you will be covering in the upcoming book?

My next Richard book is a continuation of the first; the project was conceived as a two-part biography with a view to telling Richard’s story in depth. As such, the second volume will pick up where the first one ended and cover the events that touched Richard’s life, including the trial and execution of George, Duke of Clarence, the death of Edward IV, Richard’s accession and coronation, as well as the rebellions against him, his foreign policy and his political vision. It will also include personal details, such as his favourite foods, interests and pastimes.

With thanks to Amberley Publishing.

Dr Josephine Wilkinson is an author and historian. She received a First from the University of Newcastle where she also read for her PhD. She has received British Academy funding for her research into Richard III’s early life and has been scholar-in-residence at St Deiniol’s Library, Britain’s only residential library founded by the great Victorian statesman, William Gladstone. She now lives in York, Richard III’s favourite city.

Visit Dr. Wilkinson at Josepha Josephine Wilkinson.

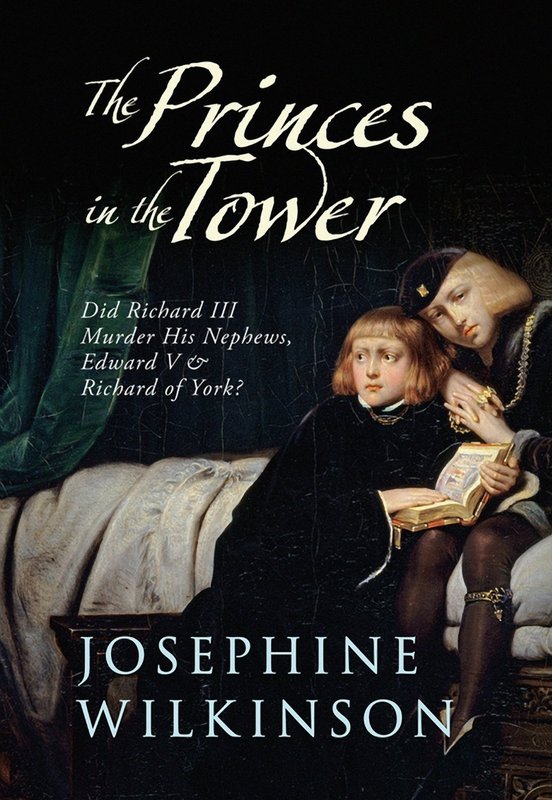

The Princes in the Tower: Did Richard III Murder His Nephews, Edward V & Richard of York? by Josephine Wilkinson. Published by Amberley Publishing 2013

The Princes in the Tower: Did Richard III Murder His Nephews, Edward V & Richard of York? by Josephine Wilkinson. Published by Amberley Publishing 2013

Buy The Princes in the Tower: Did Richard III Murder His Nephews, Edward V & Richard of York?

In the summer of 1483 two boys were taken into the Tower of London and were never seen again. They were no ordinary boys. One was the new King of England; the other was his brother, the Duke of York, and heir presumptive to the throne. Shortly afterwards, their uncle, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, took the throne as Richard III. Soon after, rumours began to spread that the princes had been murdered, and that their murderer was none other than King Richard himself. Since 1483 the dispute over Richard’s guilt or innocence has never abated. The accusations, which began during his own lifetime, continued through the Tudor period and beyond, remaining a source of heated debate to the present day. For much of this time it has been taken for granted that Richard murdered his nephews to clear his path to the throne, but there are other suspects. One is Henry VII, Richard’s successor, who is alleged to have discovered the princes in the Tower following his victory at Bosworth. Recognising them as the rightful heirs to the throne, he ordered their deaths. More recently another suspect has come forward: Henry, Duke of Buckingham, who was motivated by personal and dynastic ambition. Yet the evidence that the princes were murdered at all is far from conclusive; could it be that one, or both, princes survived? Now, in the wake of the discovery of Richard III’s remains in a car park at Leicester, it is time to revisit the question of what became of his nephews, the boys known to history as the Princes in the Tower. This study returns to the original sources, subjecting them to critical examination and presenting a ground-breaking new theory about what really happened and why.