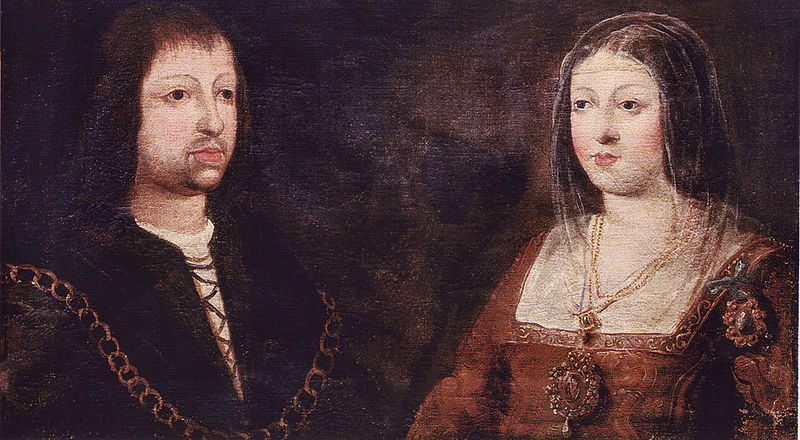

The marriage of Henry Tudor and Elizabeth of York was not a love match. It was arranged by their mothers during their years of suffering under King Richard III. Margaret Beaufort and Elizabeth Woodville, one woman under house arrest and one in sanctuary, agreed that Henry Tudor should move to claim the throne from Richard III. Once he had taken it, he would marry Elizabeth of York, uniting the two rival Houses of Lancaster and York. In December 1483, in the cathedral in Rennes, Henry Tudor swore an oath promising to marry Elizabeth, and began planning an invasion.

Henry was victorious in the battle of Bosworth, the last battle of the Middle Ages. He did not, however, march into London and sweep his bride off her feet. This is not a fairytale. Much is made of the five-month gap between Henry VII taking the throne and his marriage to Elizabeth of York. That the coronation of Henry VII took place a few months before his marriage to Elizabeth of York is often seen as an attempt to distance himself from his wife’s own claim to the throne. This is hardly a likely scenario. Despite the fact that Elizabeth of York was considered the rightful York heir to the throne, no-one was expecting, or hoping for, her to rule as Queen Regnant. One only needs to look at the disastrous marriages of her son Henry VIII to see how the nobility felt about a woman’s rule. Henry did indeed need to be declared King in his own right, the Battle of Bosworth may have been won, but one must be anointed and crowned.

Other more sinister, purely fictional interpretations abound. Some lately include the theory that Henry wanted to wait and see if Elizabeth was pregnant by her uncle Richard III. But there is no proof nor contemporary rumours that Elizabeth of York ever had an affair with King Richard III. Some Richard III admirers have sought to attribute any manner of cowardly and vile acts to Henry Tudor including forcing Elizabeth into his bed before the marriage to “test” if she was a virgin or the raping of his betrothed to see if she was fertile. To accuse Richard III of defiling his own niece or Henry Tudor of raping his betrothed needs to be considered only with the contempt it deserves. Let’s take a look at the facts.

A Long Engagement

So why the five month gap? Henry Tudor was victorious at Bosworth on the 22nd of August 1485. On the 15th of September writs were issued for Henry VII’s first parliament to be held on November 7th1. By then Elizabeth was installed at Coldharbour, the home of Henry’s mother Margaret Beaufort 2. Henry’s coronation was held on the 30th of October, a week before his first parliament. One of the most important issues to deal with was Titulus Regius, the act passed by Richard III that declared the marriage of Elizabeth Woodville and Edward IV as illegal and their children illegitimate. Elizabeth’s legitimacy and rightful titles had to be restored before the wedding could go ahead, and the act was repealed in Henry’s first parliament. By now, the couple, who had probably never met before, were getting to know each other in the relative privacy of Coldharbour.

By December Elizabeth’s wedding ring had been ordered. Henry was also busy acquiring the necessary Papal dispensations, for the couple were related by blood in the double fourth degree of consanguinity3. Three dispensations would be issued in total. The first dispensation had been issued sometime before March of 1484, when Elizabeth Woodville and Margaret Beaufort had first arranged the marriage in rebellion against King Richard III. However secrecy was essential lest Richard seek to thwart the marriage, and the dispensation was issued for a “Henry Richmond” and “Elizabeth Plantagenet”. Henry went about applying for a second dispensation after he took the throne, which arrived on the 16th of January 1486. The couple were married a mere two days after the dispensation arrived, which makes it obvious the dispensation was the main cause of delay. The third and final dispensation would not arrive until March 2nd, by which time the couple were wedded and bedded and Elizabeth pregnant.

Henry was determined to make the marriage indisputable, and the third dispensation removed the impediment of a possible fourth degree of affinity, relation through marriage4. This is hardly surprising considering Richard III was able to seize the throne by disputing his older brother’s marriage. Henry would take no such chances. So is a five-month gap really such a long period of time? Henry had rather a lot to do after he defeated King Richard III, he hardly had time to rest on his laurels. Peace had to be established, he had to be crowned and hold his first parliament, restore his wife to her rightful position and take the time to get to know her while they were waiting for the Papal dispensation to arrive. Elizabeth was likely content enough to wait a few months in her newly furnished rooms at Coldharbour after the two years of hell she had experienced after her father’s death.

My Lady the King’s Mother

The propaganda surrounding Margaret Beaufort serves two purposes, it brings another villain into the mix in the mystery of the fate of the “Princes in the Tower” and it emasculates Henry VII. Fictional representations of Margaret show an unhealthy and obsessive love for her son in which she rivals her daughter-in-law for his affections. The most recent depiction of Margaret on television is maniacal, fanatical and outrageously sexist, for how better to denigrate a female than showing her as a hysterical woman constantly on the verge of tears, when not of course being devious and underhanded?

Henry and Margaret certainly were close. He was Margaret’s only child, born when she was merely thirteen, a difficult birth that nearly killed both of them. Margaret would never give birth to another child and was parted from Henry for most of his young life. Their affection for each other when they were finally reunited is plain in the surviving records of gifts and letters. Henry honoured his mother, she was the greatest landowner in the kingdom only after the King and Queen, declaring her femme sole, which gave her complete control over her own wealth. Margaret certainly was a constant presence at court, and was far more involved in Henry and Elizabeth’s affairs than most Kings’ mothers had been, but then Cecily Neville, mother of Edward IV, was also a constant presence during the early years of her son’s rule. Cecily even revised her coat of arms to include the royal arms of England, hinting that her husband, Richard Duke of York, had been a rightful king and that she was effectively Queen Dowager. When Edward married Elizabeth Woodville, he built new queen’s quarters for her and let his mother remain in the queen’s quarters in which she had been living.

Cecily Neville and Margaret Beaufort, in fact, held each other in great esteem. Considering Cecily was almost thirty years older than her and it is not inconceivable that Cecily’s influential role at court left an impression on a younger Margaret. Both had active political roles in the early years of their sons’ reigns. Both were afforded semi-regal status by their sons. Many observations have been made of Margaret Beaufort appearing in similar attire to her daughter-in-law the Queen, taking precedence just a step behind her. A miniature from the Lutton Guild Book (c 1475) shows Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville kneeling before an image of the Trinity. Cecily is depicted in royal robes, placed immediately behind the queen. 5 As Amy Licence points out, on key occasions such as Twelfth Day Elizabeth and Margaret appeared in “like mantle and surcoat” but then Margaret tended to her daughter-in-law’s crown as Elizabeth feasted.6

The difference between Margaret Beaufort and Cecily Neville is that Cecily was outraged at her son marrying the commoner Elizabeth Woodville. Margaret, however, had actively worked towards her son’s marriage to Elizabeth of York and may have been cherishing the idea long before Richard III took the throne. Her husband Stanley would recall that “long before communing was had between the said lord Henry and lady Elizabeth about contracting marriage, the said sworn [witness] heard Richard, earl of Salisbury, and the lady Margaret, wife of this sworn [witness], mother of the said king that now is, and divers other noble and illustrious persons saying that the said king Henry and lady Elizabeth were related in the fourth and fifth degrees of kindred, and reciting the degrees aforesaid, and affirming that they were true degrees lineally drawn from the said duke of Lancaster.”7. Margaret had been negotiating with Edward IV to bring Henry out of exile for years and was Edward was perhaps considering marrying Henry to one of his daughters to reign him in, he was after all the Lancastrian heir and still a threat. A draft of pardon (undated) from Edward IV to Henry Tudor is written on the back of the patent of creation of Edmund Tudor as Earl of Richmond on 23 November 1452 suggest he may have been considering granting him his former title again. 8

So did Elizabeth of York resent her mother-in-law’s dominant presence at court? That Margaret was commanding and imperious cannot be denied, but then nor can her affection for both her son and daughter-in-law. There is no evidence Henry favoured his mother over his wife. A letter from Pope Alexander warned Margaret that Henry had already promised Elizabeth that he would appoint her candidate as the next bishop of Worcester, therefore Margaret’s candidate had to be dropped. 9 The most oft-repeated accounts of Margaret’s alleged dominance over her daughter-in-law are from the Spanish ambassadors. The first from Pedro de Ayala is usually repeated in this fashion “The King is much influenced by his mother…the Queen, as is generally the case, does not like it.” These two sentences are most often chosen to represent what he said, yet looking at the entire portion of the letter gives it a slightly different context.

“The King is much influenced by his mother and his followers in affairs of personal interest and in others. The Queen, as is generally the case, does not like it. There are other persons who have much influence in the government, as, for instance, the Lord Privy Seal, the Bishop of Durham, the Chamberlain, and many others.“10

de Ayala is in fact speaking of several persons who had a strong influence over the King, including his mother. That “The Queen, as is generally the case, does not like it” means, quite obviously, he is making a generalisation. It is not sound evidence of Elizabeth’s actual feelings nor that Henry would only listen to his mother in matters of state.

More telling perhaps is the letter from the sub-prior Of Santa Cruz to Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, the parents of Prince Arthur’s betrothed, Katherine of Aragon. “The Queen is a “very noble woman,” and much beloved.” he wrote “She is kept in subjection by the mother of the King. It would be a good thing to write often to her, and to show her a little love.”11 This rather touching note on the end may indicate the sub-prior suspected Elizabeth could use a little more respect and attention, but this is purely speculative, on both his part and ours.

Another more obscure account is of John Hewyk of Nottingham, who was seeking a position in the Queen’s household “that he had spoken with the Queen’s Grace, and should have spoken more with her said Grace, had [it] not been for that strong whore the King’s mother.”12 It appears Margaret intervened on this occasion, yet again this is not indicative that Margaret was being domineering, she may have in fact intervened to get rid of an intrusive man, if his manners indeed are anything to go by. Publicly the two women put on a united front and collaborated on many projects together. It is unlikely that the Queen would let her frustration at her mother-in-law show in front of strangers. Elizabeth had a lifetime of royal training, she would have borne her mother-in-law’s less desirable qualities with her famous good grace.

It was Margaret who intervened for Elizabeth’s younger sister Cecily when she angered Henry with her marriage to a commoner, Margaret who gave Cecily and her husband shelter and negotiated with Henry on Cecily’s behalf so Elizabeth would not be placed in a difficult position. It was Margaret who looked after Elizabeth in the aftermath of Bosworth, newly renovating her rooms to keep her comfortable and allowing her the privacy to get to know her future husband. Margaret kept a permanent suite of rooms entirely for Elizabeth’s disposal at her estate in Collyweston. It was to Margaret’s house that Elizabeth fled with Prince Henry during the Cornish uprising of 1497. It was Margaret to whom Elizabeth turned when she was anxious about her daughter being sent to Scotland. Margaret had, after all, also experienced a dangerous childbirth at a tender age. Henry told the Spanish ambassadors-

“Besides my own doubts, the Queen and my mother are very much against this marriage. They say if the marriage were concluded we should be obliged to send the Princess directly to Scotland, in which case they fear the King of Scots would not wait, but injure her, and endanger her health.”13

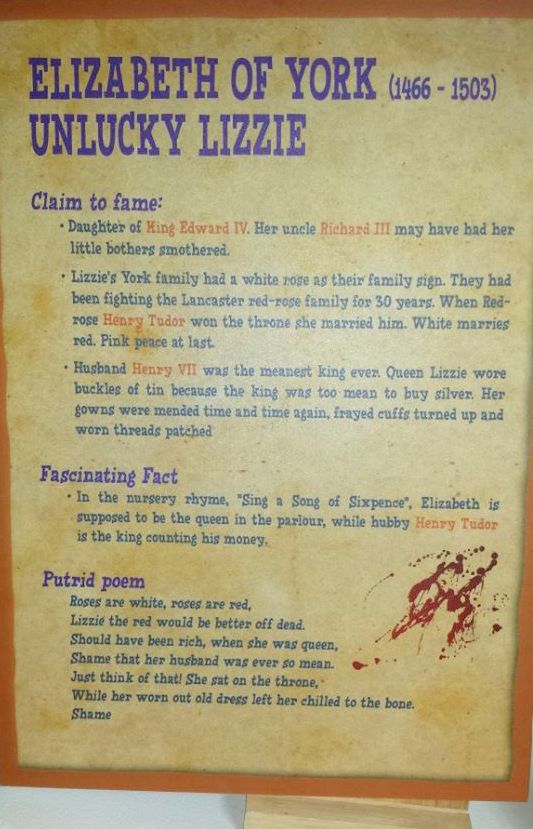

Penury

One of the sillier myths surrounding the marriage of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York is that he kept her short of money and forced her to wear threadbare gowns that were mended over and over again. Henry always opened his purse when it came to spending money on his family, that a King who was so concerned with keeping a regal appearance would keep his Queen in rags beggars belief. However, to briefly address the gowns we need to look at Elizabeth of York’s Privy Purse Expenses.The first mentions payments to her tailor.

“It͠m the same day to Robert Ragdale tailour for making of two dublettes for twoo fotemen…It͠m for lynyng a gowne of blake velvet for the Quenes grace with wyde slevys with blake sarcenet with an egge of blake sattayne…and for mendyng of divers gownes and kirtelles of the Quenes” 14

It mentions “divers gowns” for mending, certainly. She was also paying her tailor for a new dress and two doublets of velvet for her footmen. Velvet was of course a luxury fabric and could not be washed in the usual way. The next mention of mending points out two velvet gowns.

“It͠m payed for the hemmyng of a kertelle of the Quenes of damaske…It͠m for mendyng of a crymsyn velvet gowne… It͠m for mendyng of a gowne of blake velvet…” 15

The tin buckles? Her wealthy mother-in-law wore the same, made from latten, a copper alloy. Was Elizabeth being forced to mend her gowns or was she merely mending some of her favourites? As Professor Arlene Okerlund told us “Such thrift is not a sign of penury or miserliness, but a sensible means of preserving elaborate gowns carefully crafted from expensive fabrics. If the myth implies that Elizabeth lacked the appropriate dress and accoutrements for a queen of England, a quick review of her “Privy Purse Expenses” will dispel that misunderstanding.”

Elizabeth was often short of money. Part of the problem was her generosity, she gave away thousands of pounds in gifts, huge tips to her servants and cash gifts to the poor who brought her small gifts of food. Alison Weir notes that “many poor folk came to the palace gates with humble offerings, such as butter, chickens, wardens (pears), pippins, puddings, apples, peascods, cakes, cherries in season, a conserve of cherries (several gifts of cherries are recorded, so they must have been known as among Elizabeth’s favorite foods), pomegranates, oranges, comfits (candied fruit), cheeses, several bucks, wild boar, tripes, chines of pork, a goshawk, pheasant cocks, capons, birds, a crane, Rhenish wine, roses, fine ironwork, and a cushion. None went away without a handsome reward, usually more than Elizabeth could afford. One man got 13s.4d. [£320] for bringing her a popinjay (parrot)”. Elizabeth also financially supported her sisters, she supported orphans, took children under her wing and raised them, and liberated debtors from London prisons. 16

Elizabeth loved good clothing, music, books and wine, she had her own pair of minstrels that travelled with her. She simply spent more than her yearly income, this is hardly unusual. As for Henry not giving her enough income, his frequent gifts not only included luxury items but everyday small items, meaning he supplemented her household out of the royal treasury. His wedding gift to his bride was 49 timbers of ermine for her Easter gown, totalling £44 2s, the equivalent of £28,950.00 today. Perhaps a £30,000 gown was worth mending.

A Loving Marriage

Henry VII’s reputation as a miserly king really began after the death of Queen. They, by all accounts, had a deep mutual affection and respect. Elizabeth had given him the family he sorely lacked in his own childhood, she was beautiful and beloved by not only her husband and children, but by all of her peers and subjects. Unlike his Elizabeth’s father or his own son, Henry never took a mistress, even though his wife was pregnant many times. It is plain he loved her. Henry was an indulgent husband. His frequent gifts to his wife were not all practical, one was a lion “for the Queen’s Grace,” costing £2.13s.4d. [£1,300], no doubt sent straight to the royal menagerie in the Tower 17 but rather a fun gift. He gave way to her when she insisted, as the Spanish ambassador reported

“Gave the Queen two letters from them, and two letters from the Princess of Wales. The King had a dispute with the Queen because he wanted to have one of the said letters to carry continually about him, but the Queen did not like to part with hers, having sent the other to the Prince of Wales.”18

It was the first terrible tragedy that struck their family that shows us something of their bond. When Prince Arthur unexpectedly died, it was Henry’s confessor that was left to break the news to him

“When his Grace under- stood that sorrowful heavy tidings, he sent for the Queen, saying that he and his Queen would take the painful sorrows together.After that she was come and saw the King her lord, and that natural and painful sorrow, as I have heard say, she, with full great and constant comfortable words besought his Grace that he would first after God remember the weal of his own noble person, the comfort of his realm, and of her. She then said, that my lady, his mother, had never no more children but him only, and that God by his grace had ever preserved him, and brought him where that he was. Over that, how that God had left him yet a fair prince, two fair princesses ; and that God is where he was, and we are both young enough ; and that the prudence and wisdom of his Grace sprung over all Christendom, so that it should please him to take this according thereunto. Then the King thanked her of her good comfort. After that she was departed and come to her own chamber, natural and motherly remembrance of that great loss smote her so sorrowful to the heart, that those that were about her were fain to send for the King to comfort her. Then his Grace, of true, gentle, and faithful love, in good haste came and relieved her, and showed her how wise counsel she had given him before ; and he, for his part, would thank God for his son, and would she should do in like wise.”19

It is often glimpses of grief that give us the best insight. Elizabeth died less than a year later trying to give her husband another son. Henry VII would never truly recover from his beloved wife’s death. While the entire nation grieved the loss of their Queen Henry ordered his council to prepare the Queen’s funeral and went into seclusion. Her “departing was as heavy and dolorous as to the King’s Highness as hath been seen or heard of”. “Solemn dirges and Masses of requiems” were heard, Henry ordered 636 masses to be offered for her soul in London alone on the day after her death. Her State funeral was one of the most lavish ever seen.

Henry ordered clothing in blue and black, blue being the royal colour of mourning, and even had his books bound in blue velvet. It would be more than a year before the King’s grief would begin to subside, shortly after her death he became seriously ill and was close to death, Margaret fled to his side to nurse him herself. He emerged from his illness a changed man. The Tower of London, where Elizabeth had died giving birth, was abandoned as a royal residence. He did briefly consider other marriages, but he never did remarry. It might be overly-romantic to think his heart never mended, but Henry VII honoured his wife every year until his own death. Every February 11th a requiem mass would be sung, the bells would be tolled and 100 candles would burn in her honour. Henry retained the services of Elizabeth’s minstrels, who played for him at every New Year celebration up to his death. He now lies with his beloved wife in Westminster Abbey.

- Chrimes, S.B, Henry VII, Yale University Press 1999, pg 65 ↩

- Underwood, Malcolm G., Jones, Michael K., The King’s Mother Cambridge University Press, pg 65 ↩

- Okerlund, Arlene Elizabeth of York Palgrave Macmillan 2011, pg 52 ↩

- Okerlund, Arlene Elizabeth of York Palgrave Macmillan 2011, pg 53 ↩

- Underwood, Malcolm G., Jones, Michael K., The King’s Mother Cambridge University Press, pg 70 ↩

- Licence, Amy Elizabeth of York: The Forgotten Tudor Queen, Amberley Publishing 2013 pg 157 ↩

- Calendar of Papal Registers Vol XIV July 1484-92 ↩

- Underwood, Malcolm G., Jones, Michael K., The King’s Mother Cambridge University Press, pg 61 ↩

- Okerlund, Arlene Elizabeth of York Palgrave Macmillan 2011, pg 136 ↩

- Calendar of State Papers Spain Vol I July 1498 210 ↩

- Calendar of State Papers Spain Vol I July 1498 205 ↩

- Weir, Alison Elizabeth of York: The First Tudor Queen, Jonathan Cape 2013, pg 204 and Underwood, Malcolm G., Jones, Michael K., The King’s Mother Cambridge University Press, pg 161 n 67 ↩

- Calendar of State Papers Spain Vol I July 1498 210 ↩

- Privy Purse Expenses of Elizabeth of York ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Weir, Alison Elizabeth of York: The First Tudor Queen, Jonathan Cape 2013, pg 198-199 ↩

- Weir, Alison Elizabeth of York: The First Tudor Queen, Jonathan Cape 2013, pg 274 ↩

- Calendar of State Papers Spain Vol I July 1498 202 ↩

- “Privy purse expenses of Elizabeth of York : wardrobe accounts of Edward the Fourth. With a memoir of Elizabeth of York, and notes” ↩