An oft-repeated excerpt from The Crowland Chronicle Continuations claims that the chronicler called the Christmas festivities at Richard III’s court “shameful” and that “during this Christmas festival, too much attention was paid to singing and dancing and to vain exchanges of clothing to Queen Anne and the Lady Elizabeth.” While this seems to have given Richard III a reputation for wild parties in some quarters, the “shameful”, or “grievous” activities, depending on the translation, referred not to festivities, but to the collection of benevolences and other (non-Christmas) activities the chronicler deigned not to dwell upon. The reference to Queen Anne and Elizabeth of York was in light of the rumours that manifested because of the affectionate display between an aunt and niece that had a disparate social standing. The anonymous chronicler did note that the actual Christmas festivities “were solemnly held in the palace of Westminster” and that on Epiphany Richard wore his crown and took “a distinguished part in the festivity in the great hall as though at his original coronation”.1

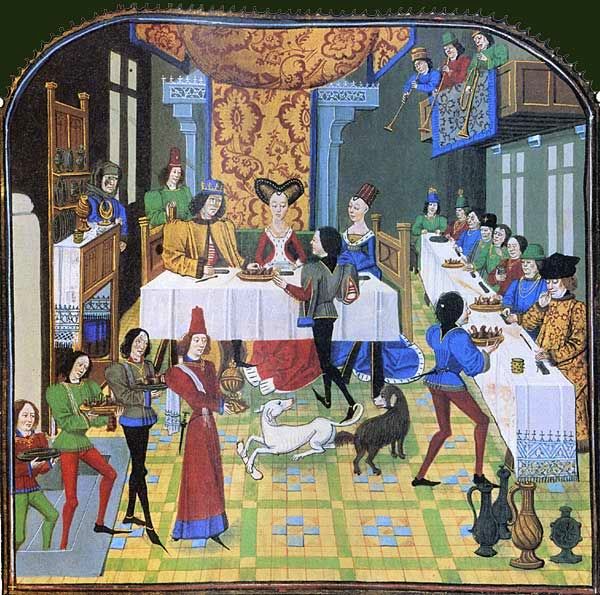

‘Solemnity’ does not necessarily indicate a particularly low-key affair, of course. The Christmas festivities in the court of Richard III would have taken place with as much pomp and ceremony as any other court. While we have no extensive reports of Christmas at Richard III’s court we can piece together the typical rituals and dishes that would have been a part of a medieval Christmas feast. The feast would have taken place in the great hall with long trestle tables lining one or both sides of the hall for guests, and the high table on a raised dais, with the host or guest of honour seated under a canopy. Richard and Anne Neville would have been seated below the canopy of estate. The rest of the diners at the high table sat on stools, or sometimes a shared settle, a high-backed wooden bench. At the far end of the hall a carved wooden screen concealed the passage leading to the kitchens. 2

The high table was laid with three cloths, the lowest cloth called the couch, and the other two cloths arranged over the front and back of the table. The cup-board, another board set on trestles, backed by shelving, was also laid with an extravagant cloth. The shelves displayed elaborate silver-gilt and silver drinking vessels, with the board itself holding the special cups for the king, and his ewer and basin for personal hand-washing, with ewers and basins for the other high-table guests at the sides.3 Hand-washing was an important ritual at feasts where guests would use their fingers to eat their meat – the guests at the lower table used a ‘laving-place’ or ‘ewery’ equipped with the essentials. A highly elaborate salt-cellar would have graced the high table, set on the king’s right. Richard III owned a gold salt cellar in the form of an elephant carrying two damsels and a castle bearing the salt upon his back, encrusted with jewels and the salt cover topped with a great pointed diamond nestled in a white rose. 4

At the high table, individual place settings were comprised of the bread trencher, a knife and spoon resting on a napkin, and small manchet loaves, the fine white bread consumed by the upper classes, to accompany the meal. The whole place setting would then be covered with another napkin. When the kitchen announced the meals were ready, the ‘surnappe’, a long cloth, would be taken to the high table and unfurled to protect the guests clothing and place settings while they washed their hands. Then, assays, tests for poison, were carried out. Various officials of the household would dip small triangles of bread into pottages and meats, drink a few drops of wine and even test the hand-washing water for poison. At the lower tables guests would wash their hands and then be escorted to their seats by rank and precedence, and grace was said. 5

The menus for Richard III’s coronation give us a good idea of some of the sumptuous banquet dishes that would have been served at a royal Christmas feast, along with traditional Christmas dishes. The Boar’s head was a long-standing traditional dish, served ‘with the snout well-garlanded’, usually with bay leaves and rosemary.

Venison, another favourite amongst the nobility, was often served with frumenty, a spiced porridge.

Take a quart of sweet Cream, two or three sprigs of Mace, and a Nutmeg cut in half put into your Cream, so let it boil, then take your French Barley or Rice, being first washed clean in fair water three times, and picked clean, then boil it in sweet milk till it be tender, then put it into your cream, and boil it well, and when it hath boiled a good while, take the yolks of six or seven eggs, beat them very well, and thick∣en on a soft fire, boil it, and stir it, for it will quickly burn, when you think it is boiled enough, sweeten it to your taste, and so serve it in with Rose-water and Musk Sugar, in the same manner you may make it with wheat. 6

Some of the birds listed on the menus of Richard III’s coronation feast included pheasant, cranes, capons, chickens, herons, partridge, egrets, quails, geese, cygnets and peacocks. The somewhat humble goose was a favourite dish for Christmas before the turkey was introduced in the 16th century. Geese were often raised alongside chickens and fed rich cereal mixes to keep them in “good grease”, or well-fattened, for the table. The barbaric force-feeding of geese to fatten their livers, now eaten as foie gras, was well-established by the early modern period.7 On Richard’s table it would have likely been served roasted and accompanied by a garlic sauce, made with wine or verjuice; sauce madam, where the goose was stuffed with fruit and spices to form a rich sauce; or ‘gauncil’, a thick flour-based sauce.

Sauce Madame

Take sage, parsley, hyssop and savoury, quinces and pears, garlic and grapes, and stuff the geese therewith, and sew the hole that no grease come out, and roast him well. And keep the grease that falleth thereof. Take galytyne and grease and add in a posset; when the geese be roasted enough; take and smite them into pieces[…]and add in a posset and put therein wine if it be too thick. Add thereto powder of galangal, powder-douce and salt and boil the sauce and dress the Geese in dishes and lay the sauce onward.

Sauce for a Goose

Take parsley, grapes, cloves of garlic, and salt, and put it in the goose, and let roast. When the goose is ready shake out that which is within, and out it all in a mortar, and do thereto, and add to it three hard yolks of eggs, and grind altogether, and temper it with verjuice, and cast it upon the goose in a fair charger and serve it forth. 8

Peacock would have certainly been featured, and the cooks went to great lengths to dress the birds back in their feathers after roasting.

Peacock Roasted

Take a peacock, break his neck, cut his throat and flay the skin and the feathers together, with the head still on the skin of the neck, keeping whole the skin and the feathers together, draw him like a chicken, keeping the neck bone whole. Roast him, setting the bone of the neck above the spit, as if he were sitting alive, and the body above the legs, as if he were sitting alive. When he is roasted enough, take him off and let him cool; and then winf the skin with the feathers and the tail around the body, and serve him as if he were alive. Or else pluck him clean, and roast him, and serve him as you do a chicken.9

Quail may not sound like a great delicacy to us now, but they were not particularly abundant in England in the middle ages. Quails had fallen out of favour with the Romans, who feared that the quail’s habit of feeding on hemlock would cause poisoning. Thus, quails rarely appear in medieval or later cookbooks, but there is some record of quail breeding becoming popular around 1600. Robert May, whose Accomplisht Cook was published in 1660, gives instructions on feeding quails, along with pheasants, partridges and wheatears. Before the 17th century quails were often simply imported from Calais, live in small cages, supplied with food and water. Instructions for roasting quails are reasonably simple, and sauce gamelyne, a tart sauce of vinegar, wine and spices, is suggested as an accompaniment.

Sauce gamelyne

Take fair bread, and cut it, and take vinegar and wine, and steep the bread therein, and draw it through a strainer with powder of cinnamon, and draw it twice or thrice until it be smooth; and then take powder of ginger, sugar, and powder of cloves, and cast thereto a little saffron and let it be thick enough and then serve it forth. 10

There was no separate ‘banquet’ course for sweets in the middle ages, that would evolve later from the ‘void’, the wine and spice course, but sweet dishes were served alongside savoury to be enjoyed after the savoury dishes. Richard’s coronation feast featured some custards, baked oranges and quinces and dates in ‘compost’ (compote), and the fantastic sugar-craft ‘subtleties’ made famous during the period; all of which would have featured at a Christmas feast. Inventories also show purchases of strawberries, figs, pomegranates, gold leaf and barrels of honey, along with a array of spices and sugar. The Forme of Curye lists custard tarts as ‘daryols’.

Daryols

Take cream of cow milk, other of almonds, do thereto eggs, sugar, saffron and salt. Mix it fair, put in a coffin two inches deeo, bake it well and serve it forth. 11

Thomas Dawson’s later recipe emits the tart shells.

To Make a Custard

Break your eggs into a bowl, and out your cream into another boewl. Strain your eggs into the cream. Put in saffron, cloves and mace, and a little cinnamon and ginger, and, if you will, some sugar and butter. Season it with salt. Melt your butter and stir it will the ladle a good while. Dub your custard with dates and currants. 12

The feast would then conclude with wine, spices and wafers. Withdrawing to another room for the ‘void’, as it was called, also allowed for the dining hall to be cleared and the servants to eat. In wealthy households ‘servants’ often included the nobility serving in ceremonial positions, so guests would wait until the servants had finished their meal. Then the servants would return after their meal to serve. The spice plates served after a meal contained elegant little comfits, spices coated in sugar. This was a lengthy process, spices such as caraway, coriander seeds and chopped ginger were placed in a swinging copper pan set over a chafing dish of charcoal. Sugar syrup was added gradually and hand-stirred until a hard, smooth coating was achieved. The spices were thought to aid digestion. Wafers were also served, and a royal kitchen would have a wafery dedicated to making the fine biscuits from a spiced batter. The spice course was just another display of wealth and luxury, for spices and sugars were only enjoyed by the wealthy who could afford them.

Of course with up to fifty dishes served in a banquet this represents just a small example of the foods Richard III’s court may have enjoyed at Christmas. But it also represents some meals that would eventually disappear from the table and be replaced; by Elizabethan times pottage was being replaced by salad, swans and peacocks were being replaced by the much more succulent turkey, and everyone’s health was starting to be affected by the huge increase in sugar intake with the addition of the banqueting course, with those barrels of honey replaced with barrels of sugar!

- Pronay, Nicholas; Cox, John; The Crowland Chronicle Continuations 1459-1486 Richard III and Yorkist History Trust, 1986 p. 173 ↩

- Wilson, Anne C. “Mediaeval Food Tradition” in Wilson, Anne C. (ed) The Appetite and the Eye, Edinburgh University Press, 1987, pp. 9 ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Hammond, PW, Sutton, Anne F., The Coronation of Richard III: The Extant Documents, Alan Sutton, 1983, pp. 283 fn 1 ↩

- Wilson “Mediaeval Food Tradition” pp. 10 ↩

- Elizabeth Grey, Countess of Kent, A true gentlewomans delight (online) ↩

- Albala, Ken, Food Through History : Food in Early Modern Europe, Greenwood Press 2003 pp. 68 ↩

- Butler, Sharon, (ed) Heiatt, Constance B., (ed) Curye on Inglysch: English Culinary Manuscripts of the Fourteenth Century, Early English Text Society, 1985, pp. 104 ↩

- Austin, Thomas, Two fifteenth-century cookery-books : Harleian MS. 279 (ab 1430), & Harl. MS. 4016 (ab. 1450), with extracts from Ashmole MS. 1439, Laud MS. 553, & Douce MS. 55, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Humanities Text Initiative 1999 ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Butler, Heiatt, Curye on Inglysch pp. 141 ↩

- Dawson, Thomas, The Good Housewife’s Jewel, Southover Press 1996, pp. 85 ↩